This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

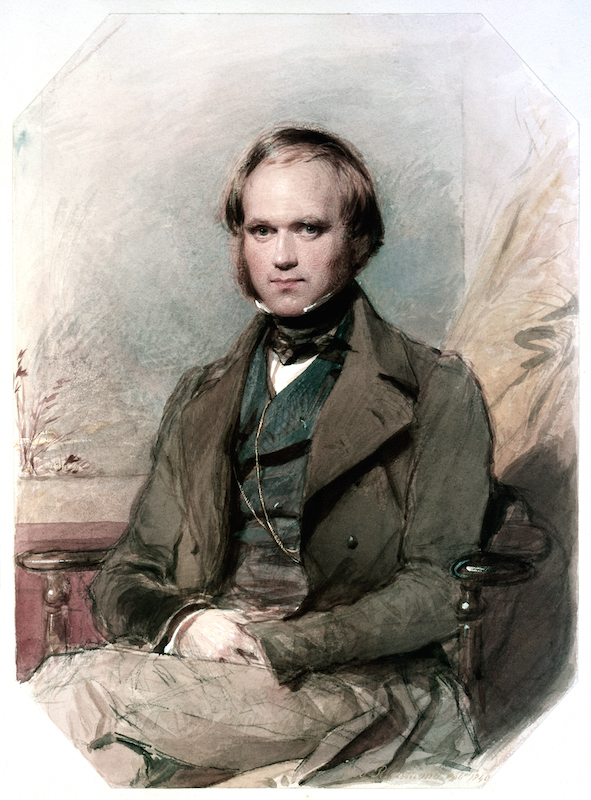

On the first sunny day of 1838, Charles Darwin decided to take a break from his studies. He left his rooms on Great Marlborough Street, fetched his horse from the stable, and rode up the bustling thoroughfare of Regent’s Street. It was, as he later wrote to his grandmother, very warm. He was headed to the Zoological Gardens, which had been opened in the new park at the end of the grand shopping parade the previous decade.

Darwin was still not used to London, much altered since he’d set off on his round-the-world voyage seven years earlier. The metropolis had been remodeled in the wake of victory in the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, made into a city worthy of the vast spread of territories it now controlled across the globe. Darwin had seen many of these lands during his travels, as the HMS Beagle had snaked its way westward, across the Atlantic and around the coast of South America before returning via Tahiti and Australia. He’d been away for four and a half years as the expedition’s gentleman naturalist, occupied in observing and collecting fossil and animal specimens.

Since his return to England, he’d been busy trying to make sense of the many crates of preserved animals, bird skins and fossils he had brought back with him. And that’s why he’d come to the Zoological Society of London: for help in understanding the 450 bird skins he had collected. In the early years of the Society’s history, there was a museum in the center of the city, on Leicester Square, that operated alongside the living collection of animals kept at the Regent’s Park. The museum’s ornithologist, Mr. John Gould, had helped him to identify numerous new species of bird, including multiple, distinct species of finch from the Galapagos Islands. These finches were all unique to the individual island from which they came, but all were still closely related to a single, mainland species.

It was these finches that first suggested to the young naturalist Charles Darwin that species might not be fixed, as it was commonly thought — that they might not have been placed, already perfect, on the earth by a supreme creator. These birds had clearly adapted from a single parent species to suit their own unique environments. And it was not long after his conversation with John Gould about the finches that Darwin came to the firm conclusion that “one species does change into another.” From that day forth, he had dedicated his every waking moment to explaining how.

In 1839, Darwin made a visit to the Zoological Society’s more popular institution: the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park. He had been there before his voyage, but now it was hugely changed. It had become one of the most popular — and exclusive — attractions in London.

The grounds had been extended westwards since the last time he was there; sheep and a calf were grazing on the new land. He walked along the terrace, which afforded him a fine view over the lawn and ponds beneath on the eastern side and the Gardens beyond. He moved on to the bear pit, where the huge animals climbed up a pole to eat sticky buns and cakes that were offered to them by zoo patrons, stuck onto walking sticks and umbrellas. He passed the other attractions of the South Garden: the camels, the twittering, vividly adorned macaws, the antelopes and zebra, the llamas, the sloth bear, and the monkeys in their crowded house, making mischief.

He continued on, into the North Garden on the other side of the drive, and to the Giraffe House at its western edge. It this large, stable-like building that housed the most celebrated attraction in the Gardens. Not the giraffes (they were old news now, though their initial arrival had caused great excitement). The new star that had replaced the giraffes in the public’s affections was a female orangutan, Jenny, kept in a railed-off section of the building.

Darwin approached her. Though he had traveled the world, it was here in London that he was seeing his first ape up close — here, in the Giraffe House of the Zoological Gardens, in an area furnished with a carpet and an armchair and a few sorry-looking trees on the other side of a barrier of bamboo lattice. Dressed in smock and trousers, she was seated on her rear on the carpet, her hairy hands with their elegant fingers clasping the bamboo as she looked towards her keeper.

Darwin watched intently as the keeper turned to Jenny and removed an apple from the pocket of his uniform jacket. She leaped up — reaching her full height of three feet — and lunged for it, but the keeper withdrew it through the bars. Jenny stopped. Waited. The keeper proffered it once more, then withdrew it again. Jenny was incensed. She threw herself on to her back, kicked her feet, and wailed in despair. Finally, the keeper said to her, “Jenny, if you will stop bawling and be a good girl, I will give you the apple.” The whining immediately diminished, though it did not cease. The keeper repeated his entreaty. The whining diminished again, and she moved gingerly towards him. He said it again, and this time she stopped whining entirely and looked up at her tormentor with hopeful eyes. The keeper handed Jenny the apple.

Darwin could hardly believe what he was seeing: an ape displaying emotions, a sense of justice, an ability to communicate. Studying this creature closely like this, he saw that an ape that was not so very different to his own species.

This was a meeting that would change the course of his thinking forever, which, in turn, would change everything.

Isobel Charman is an award-winning television producer based in London. She is the author of The Zoo: The Wild and Wonderful Tale of the Founding of London Zoo: 1826-1851, out now from Pegasus Books.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com