Most Americans know July 4 as a day to celebrate America’s declaration of independence from Britain. But July 4 is important in American history for another reason, too: it was on July 4, 1817 — 200 years ago this Tuesday — that ground was broken in Rome, N.Y., as construction began on the Erie Canal.

At the time, Americans roads were so bad that there was very little trade within the country. People who settled inland and the people on the East Coast had basically no contact with one another. “The European powers that colonized North America invested little in infrastructure, so transportation in the young United States was both poorly developed and very expensive,” says Carol Sheriff, author of The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817-1862 and professor of History at The College of William and Mary.

Construction of the canal wasn’t a pretty sight at first. New York Governor DeWitt Clinton’s political opponents started calling it “Clinton’s Big Ditch” or “Clinton’s folly.” But once the 363-mile waterway was completed in 1825, it was recognized as an engineering marvel and economic game-changer, linking up the Great Lakes and the Hudson River to transport raw materials from the Midwest to the Atlantic Coast, as well as immigrants from Europe heading inland.

Here, are six key facts to know about the route often referred to as “America’s first superhighway” during the early part of its 200-year history:

It was one big DIY project.

The Erie Canal was built by amateurs, some of whom started by going over to England to study how the country’s canals were constructed. “There were no engineers in the country, no school that taught engineering,” says Jack Kelly, author of Heaven’s Ditch: God, Gold, and Murder on the Erie Canal.

It helped popularize the terms North and South as regions of the U.S.

The canal changed the way Americans talked about the country, according to Kelly, who argues that the new waterway encouraged Americans to think about things in terms of north and south rather than east and west. And those divisions weren’t just about geography. The Erie Canal linked the regions of the U.S. that had abolished slavery by the 1820s, helping their economies. In addition, the people who settled the upper midwest were generally either religious New Englanders or immigrants, neither of which were groups that tended to practice slavery. “It was their settlement of land that blocked the southerners from moving into the region with their slaves,” says Kelly. “It was the combination of anti-slavery sentiment and physical possession of the land that intensified the North-South divide.”

It established New York City as the financial capital of the new world.

Between New York City’s position along the Hudson River and its place as a port for immigrants, the canal made the Big Apple truly big — the biggest port in America.

It shaped the history of Mormonism.

Mormons believe that the angel Moroni appeared to Joseph Smith and told him about the Book of Mormon at the Hill Cumorah in the early 1820s, near what’s now Palmyra, N.Y. The town was located along the canal route, and the Smith family had lived there since Joseph was 10, having moved from Vermont in hopes that they could claim a chunk of the prosperity generated by the Erie Canal. The area was also home to a religious revival that, amid the focus on wealth, attempted to remind people of what’s important in life. “The Smiths lost out on the prosperity, but they took advantage of the excitement to found a new and uniquely American religion,” says Kelly. “Mormonism began in Palmyra, but the Latter-Day Saints soon moved westward, first to Ohio, then to Missouri and Illinois.”

It launched America’s first boomtown.

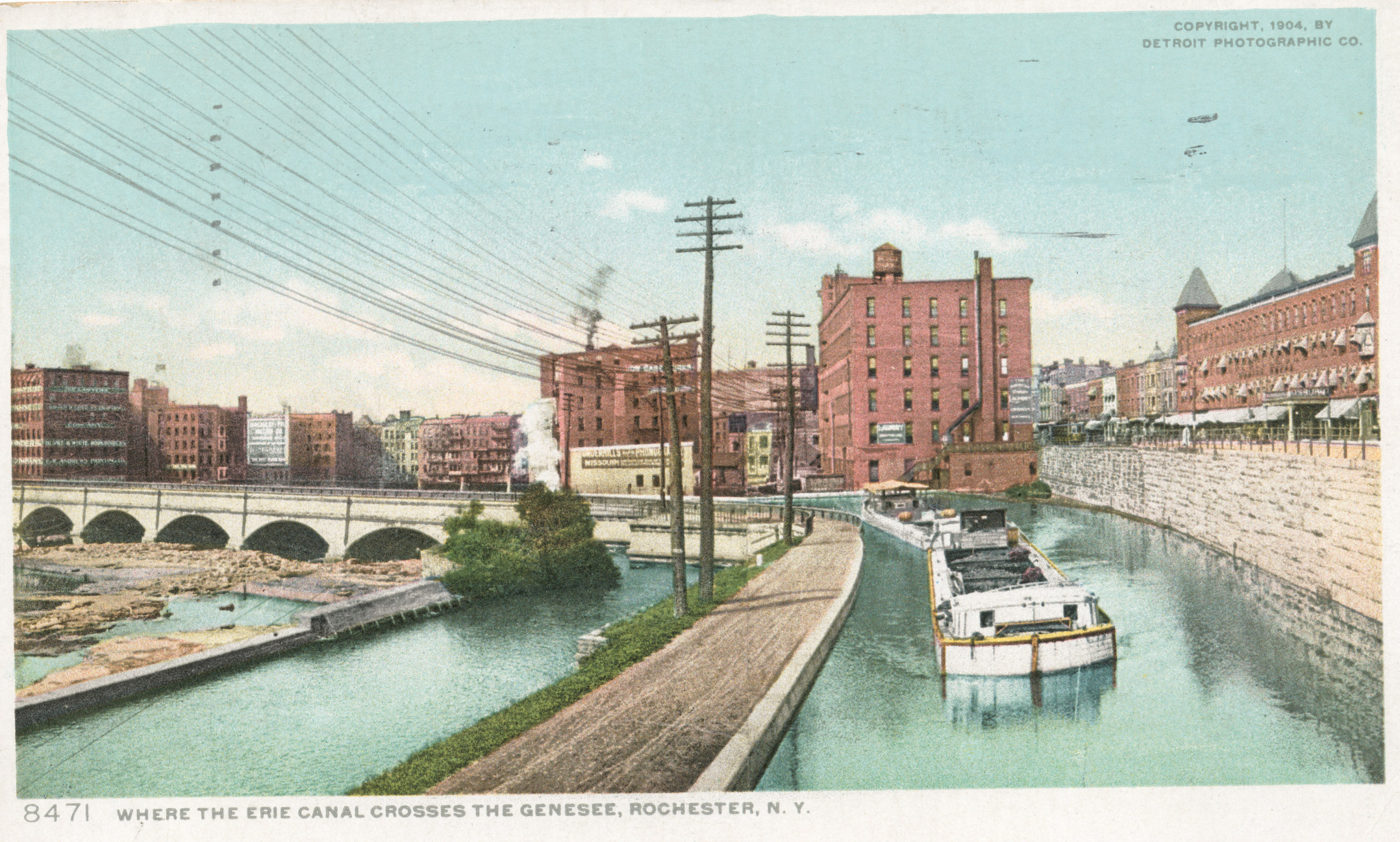

The first U.S. city to fit that term, due to its speedy growth, is believed to be Rochester, N.Y., which was home to the biggest flour mills in the area. The canal enabled the city to ship those products, leading to a boom in population and wealth.

There were no mules on the Erie Canal — but there were kids.

Despite the famous Tin Pan Alley-era folk song about the Erie Canal that rhymes the canal with a mule named Sal, horses — not mules — pulled the boats along the original Erie Canal. “A significant proportion of the early workforce was made up of children, particularly boys who helped drive the horses that pulled the canal boats, and girls who worked in the boat cabins,” says Sheriff.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com