It was 45 years ago — on June 23, 1972 — that President Richard Nixon signed the law that would quickly become known simply as Title IX. The rule, part of the Education Amendments of 1972, stipulates that any educational program or activity that receives federal funding cannot discriminate on the basis of sex. Its implications are many; recently, for example, Title IX has been the basis of complaints against schools charged with not properly responding to the issue of sexual assault. But its most famous impact has been on school sports programs. Because almost every college in the U.S. receives some kind of federal funding, female athletes were able to use Title IX to argue that schools should take women’s athletics as seriously as they did men’s.

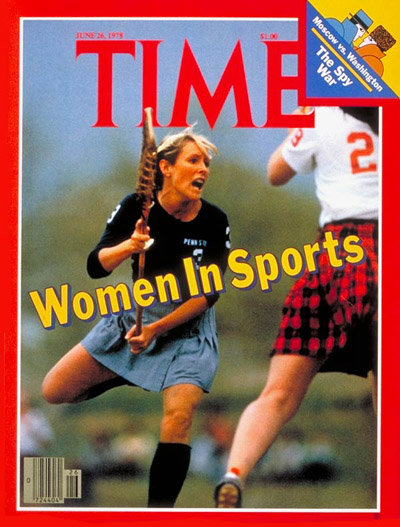

The regulation didn’t go into effect right away but, in anticipation, change had already begun when the subject was examined in a TIME cover story in June 0f 1978, right around the time when compliance would become mandatory.

Already, the magazine explained, six times as many high school girls were participating in competitive high school sports than had done so in 1970. The budget for women’s sports at North Carolina State had multiplied by 15 in just four years. The University of Michigan had not had a single formal competitive sport for women in 1973; five years later, it had 10 varsity teams for them.

And, the story noted, the effect of Title IX was not limited to elite college athletes or to public school students who also fell under the regulation’s purview. From young girls to older women who had once wished to compete, American women in the 1970s were “discovering the joys of competition,” the article explained:

No matter how important the shift in society’s attitudes, the crucial change, the enduring alteration, takes place in the lives of individuals. Each time a young girl acquires the discipline to polish an athletic skill or learns to subject her ego to the requirements of team play, she helps gain the self-confidence that marks the healthy adult. Girls are showing they can be as determined as boys. In Lee, Mass., a high school softball pitcher named Linda (“Luke”) Lucchese, 18, informs the opposing bench. “Forget it, you guys. The gate is shut.” Then she wins the game 11-4. Luke’s attitude is shared by World-Class Miler Francie Larrieu, 25: “I have learned through athletics that if you believe in yourself and your capabilities, you can do anything you set out to do. I have proved it to myself over and over.”

Researchers have found that the virtues of sport, when equally shared, equally benefit both sexes. Notes Dr. William Morgan, of the University of Arizona’s Sports Psychology laboratory: “Athletes are less depressed, more stable and have higher psychological vigor than the general public. This is true of both men and women athletes.”

If, as folklore and public policy have long insisted, sport is good for people, if it builds a better society by encouraging mental and physical vigor, courage and tenacity, then the revolution in women’s sports holds a bright promise for the future. One city in which the future is now is Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In 1969, well before law, much less custom, required the city to make any reforms, Cedar Rapids opened its public school athletic programs to girls and, equally important, to the less-gifted boys traditionally squeezed out by win-oriented athletic systems. Says Tom Ecker, head of school athletics, “Our program exists to develop good kids, not to serve as a training ground for the universities and pros.”

…Kelly Galiher, 15, has grown up in the Cedar Rapids system that celebrates sport for all. The attitudes and resistance that have stunted women’s athleticism elsewhere are foreign to Kelly, a sprinter. Does she know that sports are, in some quarters, still viewed as unseemly for young women? “That’s ridiculous. Boys sweat, and we’re going to sweat. We call it getting out and trying.” She has no memories of disapproval from parents or peers. And she has never been called the terrible misnomer that long and unfairly condemned athletic girls. “Tomboy? That idea has gone out here.” It’s vanishing everywhere.

As Senator Birch Bayh had said in 1972 when making the case for the amendment, Title IX wouldn’t solve every problem when it came to guaranteeing equality for Americans regardless of sex. But, he said, it was “an important first step in the effort to provide for the women of America something that is rightfully theirs.”

And the impact of the amendment is still being felt — according to the NCAA, in the 2015-16 academic year, 211,886 women participated in college sports in the U.S., representing a 25% increase over the previous decade.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com