In a major case on partisan gerrymandering, the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday decided — along partisan lines — that the issue presents “political questions beyond the reach of federal courts.” In other words, while Congress and the states may take steps to address gerrymandering, federal courts can’t block the practice.

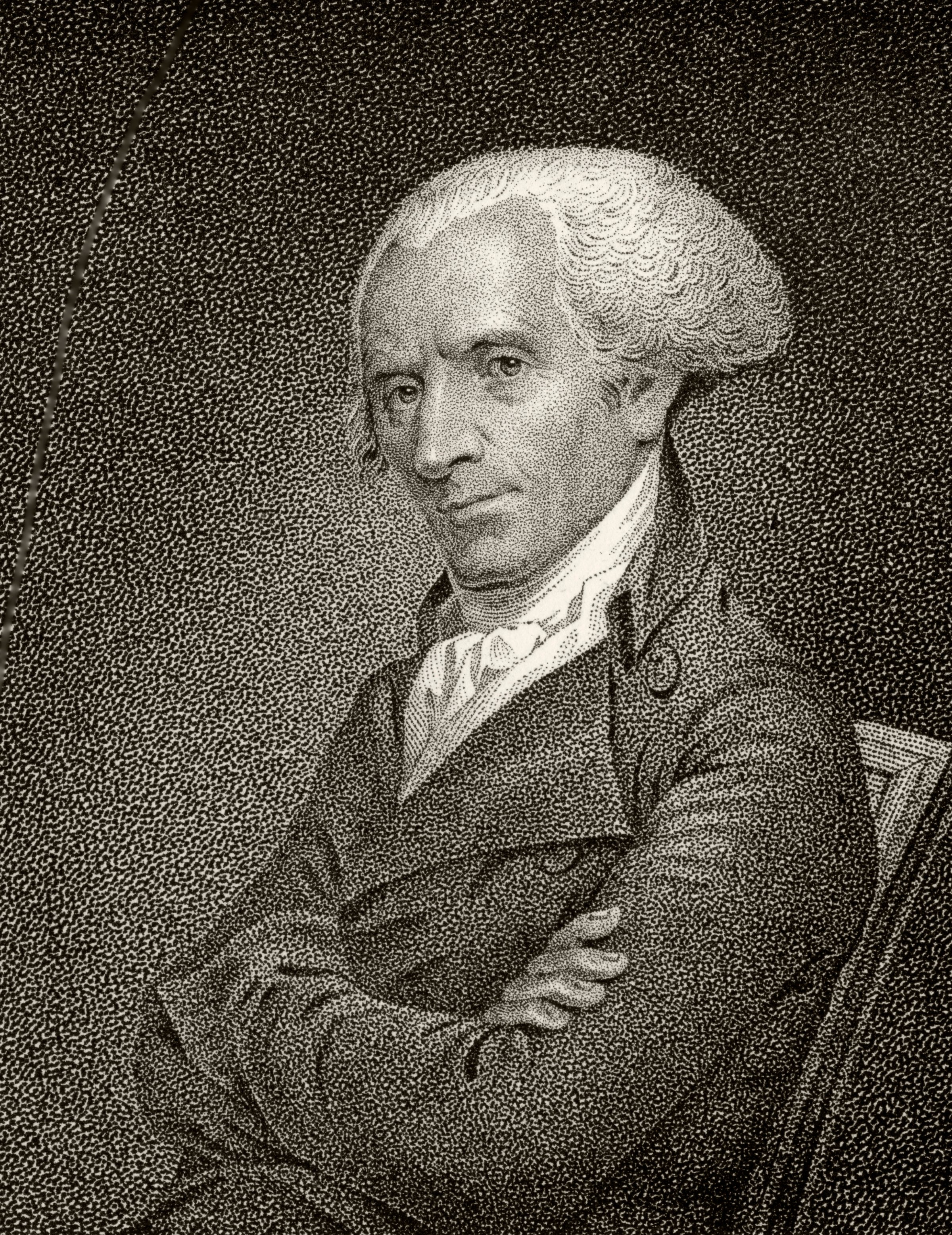

To understand how partisan redistricting came to be known as “gerrymandering,” one has to look back more than 200 years ago to an 1812 political cartoon, often credited to Elkanah Tisdale, which appeared in a pro-Federalist newspaper, the Boston Gazette. It satirizes a law signed by Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry in February 1812, which reorganized state senatorial voting districts in a way designed to secure his own position and a majority in the legislature for his party — Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans — while keeping the Federalists (the party of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton) out of power. The new districts were oddly shaped, but they had the effect of grouping or splitting voters in such a way that the results would be predictably favorable for one party or the other. The effort worked; in the election after the redistricting, the Democratic-Republicans won 29 seats and the Federalists won 11.

It’s said that the term emerged from the Gazette newsroom, at which a staffer noted that one of the new districts looked like a salamander, to which his colleague shouted out the play on words “Gerrymander!”

Gerrymandering as a word for partisan redistricting stuck — and Gerry, though he would go on to be James Madison’s vice president, did not win re-election as governor — but Gerry didn’t invent the practice. “Patrick Henry created a district in 1789 to surround James Madison, a strong supporter of the Constitution, with opponents of the Constitution and the new federal government so that Madison would lose his bid [for Congress],” says Carol Berkin, a historian of Colonial America at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY).

Gerry’s dispute with the Federalists, whom he saw as elitists, was an old one. He had detested the party since the drafting of the Constitution at the end of the 18th century, at which point he refused to sign the Constitution because he thought it “created too powerful a government and hurt Massachusetts’ independence by forcing it to cooperate with other states on commerce,” Berkin says. He also clashed with the Federalists over diplomacy, fearful that war between France and England would lead the U.S. back to its old monarchical overlords but, due to his personality, unable to sway the U.S. toward officially siding with France. (“He’s a terrible diplomat and alienates the other two men that are there to make the treaty — Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and John Marshall — who hate his guts by the end,” says Berkin.)

As the National Archives describes the sequence of events:

In 1797 President John Adams appointed him as the only non-Federalist member of a three-man commission charged with negotiating a reconciliation with France, which was on the brink of war with the United States. During the ensuing XYZ affair (1797-98), Gerry tarnished his reputation. Talleyrand, the French foreign minister, led him to believe that his presence in France would prevent war, and Gerry lingered on long after the departure of John Marshall and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the two other commissioners. Finally, the embarrassed Adams recalled him, and Gerry met severe censure from the Federalists upon his return.

After the incident, he became an ardent Jeffersonian and Democratic-Republican, siding with those he believed supported the common man. However, George Athan Billias’ biography of the politician, Elbridge Gerry: Founding Father and Republican Statesman, argues that his views on the common man weren’t as wholesome as they sounded, as he still believed that “a subordination” of the people “is necessary to good Government.” That situation — his strong partisan feelings and his belief that it was sometimes necessary for leaders to act as a check the public — helped create the situation that would forever link his name to the practice of partisan redistricting.

And his mixed feelings aren’t anything new or anything that has gone away, since redistricting is still happening.

“The life of Elbridge Gerry highlights the utopian and contradictory strains in American republicanism,” as the late historian Paul Goodman once wrote. “Fierce competition among rival elites, often narrow and self-serving, eventually became institutionalized in political parties that cloaked appeals to interest in communitarian rhetoric that promised to advance the common good… [Elbridge Gerry’s] republicanism impaled him on the horns a dilemma neither he nor we can escape.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com