This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

“The problem is mine,” Gabriel García Márquez confessed to a friend in a letter in July 1966, “that after so many years of working like an animal, I feel overwhelmed with fatigue, without clear perspectives, except in the only terrain that I like and does not feed me: the novel.” He also told his friend that he had just finished writing One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien años de soledad). But he had serious doubts about whether the novel was good at all. For the past four months he had been under the impression that the novel “embarked me in an adventure that could be either fortunate or catastrophic.”

In this “very long and very complex” novel, as he described it to Editorial Sudamericana’s acquisitions editor, García Márquez wanted to fictionalize the atmosphere of his childhood when he lived with his maternal grandparents in Aracataca, a town located in Colombia’s Caribbean region. He stayed in his grandparents’ house until the age of 8. Soon after, the memory of the house, the family, and Aracataca not only started to haunt him but also proved crucial to his successful literary career, because the reminiscences of his childhood became the seed of One Hundred Years of Solitude and some of his early fictional works, which centered around the Buendía family and the town of Macondo.

Before he took on literature, the young García Márquez had two passions: drawing and music. Although he did not pursue drawing professionally, he was known for doodling long-stemmed flowers when dedicating his books to close friends, such as the flower that appears on the first page of a photocopied typescript of One Hundred Years of Solitude that he gave to his friend Álvaro Cepeda Samudio.

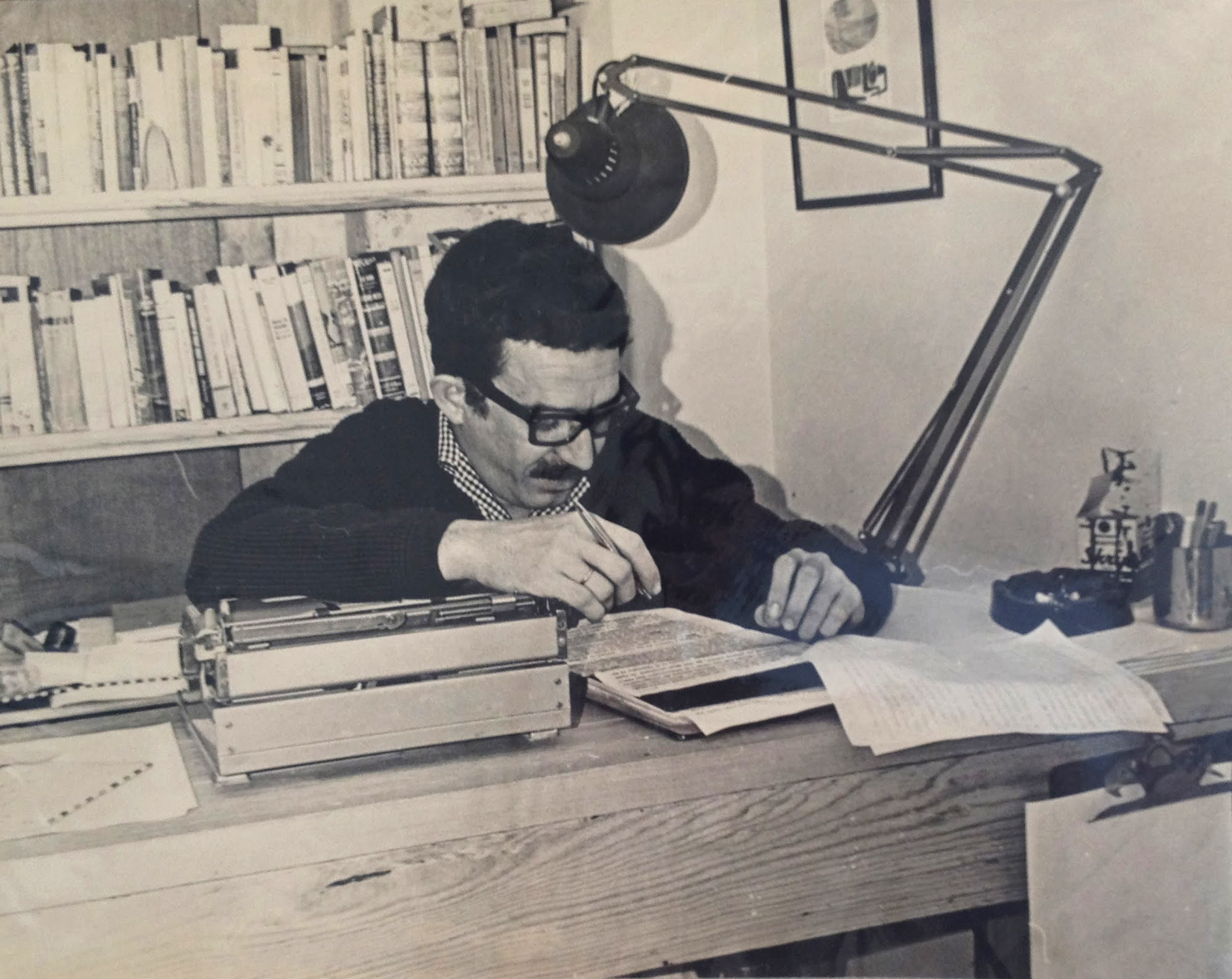

His other passion, music, permanently accompanied him. Photos of his office in Mexico City show that over the years music (first, in the form of vinyl records and cassettes, and later as CDs) occupied as much space on the shelves as his literature books. Listening to music, in fact, was as important a part of his creative process as reading was.

In March 1966, his beloved vallenatos — a popular folk music of Colombia — welcomed him to Aracataca. That month he paused the writing of One Hundred of Years of Solitude and flew from Mexico to Colombia to present Tiempo de morir at the Cartagena Film Festival. Mexican filmmaker Arturo Ripstein directed the movie and García Márquez wrote the script. After Cartagena, he traveled to Aracataca with his friend Cepeda Samudio in order to revisit the locations of his fictional Macondo, including his grandparents’ house. To García Márquez’s delight, his visit coincided with the town’s first festival of vallenato. An energized García Márquez resumed work on the novel upon return to Mexico City.

Writing took him approximately 13 months, from July 1965 to August 1966. Little documentation survives to this day to understand how he wrote it. Allegedly, García Márquez burnt all manuscripts, notes, and diagrams after receiving the first copy of the book from Sudamericana. He only saved the last version of the novel’s typescript, now kept at the Ransom Center. This typescript contains over 200 handwritten corrections, which reveal surprising textual variants with the final text of the novel published by Sudamericana. Some variants of special interest can be found on pages 46, 149, and 282.

Upon its publication on May 30, 1967, the novel achieved rapid success in Spanish-speaking countries. Yet neither the author nor the publisher expected it to succeed the way it did. At that time, they hoped One Hundred Years of Solitude would attain a success similar to other contemporary Latin American novels, such as Ernesto Sábato’s On Heroes and Tombs (1961), Alejo Carpentier’s Explosion in a Cathedral (1962), Carlos Fuentes’s The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962), Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Time of the Hero (1962), Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch (1963), Juan Carlos Onetti’s Body Snatcher (1964), and José Donoso’s Hell Has No Limits (1966). To their surprise, the novel became an international bestseller.

Given the magnitude of its success, media outlets in Latin America and Spain tried to explain the literary phenomenon of One Hundred Years of Solitude, including special publications such as the issue number 9 of Coral, a journal of tourism, art, and culture published in Valparaíso, Chile. This special issue included a compilation of critical essays on the novel written by 11 critics and writers in five countries. Enthusiastic reviews and record sales in Latin America and Spain favored an avalanche of translations. Its publication in Great Britain, in particular, included the release of a large-format, illustrated brochure stating that echoes of William Faulkner, Leo Tolstoy, and Thomas Mann were present in García Márquez’s novel. The brochure also reproduced the famous 1967 Times Literary Supplement review calling One Hundred Years of Solitude a “masterpiece.” Witnessing the novel’s international success unfold was García Márquez’s wife, Mercedes Barcha, who, as he said in multiple occasions, appears in disguise in most of his books.

Partly due to the novel’s success, García Márquez was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. Since then, the stature of One Hundred Years of Solitude has continued to grow, and its style — popularly known as magical realism — has influenced major writers and books, from Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children to Toni Morrison’s Beloved to the Harry Potter series. By now, One Hundred Years of Solitude has officially sold over 45 million copies and has been published into 44 languages, making it the second most translated literary work in Spanish after Don Quixote.

In 2007, the Royal Spanish Academy released a special edition of the novel to commemorate its fortieth anniversary. With the goal of amending the mistakes present in the original edition of 1967, the Academy asked García Márquez to re-read and edit the text for the last time, so that this edition will show the text as he originally intended it to be. According to the galleys kept at the Ransom Center, he made a total of 61 changes, most of them related to spelling errors. But he also took advantage of this final opportunity and brought to life several of the editing practices he adopted 40 years before, when revising the last version of the novel’s typescript. So in the 2007 edition he introduced some changes in the text to conform to his original intention of making the language as precise as possible; for example, he replaced “colonial organism” (p. 448) with “colonial liver” (p. 432). Other changes conform to his original idea of augmenting the geographic isolation of Macondo; for instance, he replaced “kilometers” with “leagues,” a more archaic unit of length, when referring to the distance between Macondo and the site of the signing of the Treaty of Neerlandia.

Half a century after its publication, the influence of One Hundred Years of Solitude on world literature is so deep and entrenched that, as American writer Eric Ormsby said, “‘it seems always to have existed.” Yet little could a García Márquez “overwhelmed with fatigue” in 1966 foresee that this novel would soon embark him on the most fortunate of literary adventures.

Álvaro Santana-Acuña is a Research Fellow at the Harry Ransom Center. His next book is titled Ascent to Glory: The Transformation of One Hundred Years of Solitude Into a Global Classic (forthcoming from Columbia University Press). His research on One Hundred Years of Solitude has received several awards and published in multiple media, including the American Journal of Cultural Sociology, Nexos, and Books & Ideas, and The Atlantic. He holds a PhD in Sociology from Harvard University and is an Assistant Professor at Whitman College.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com