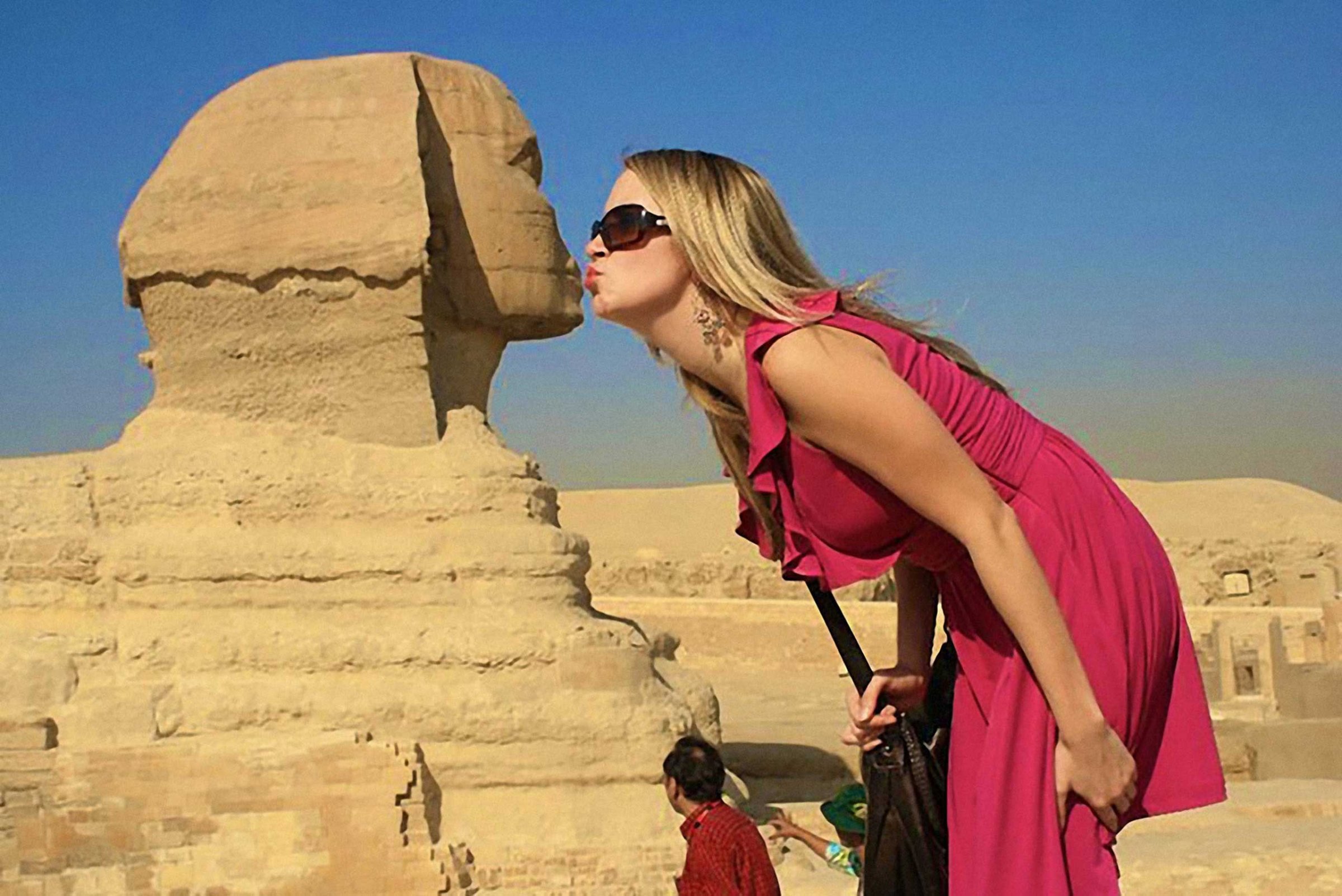

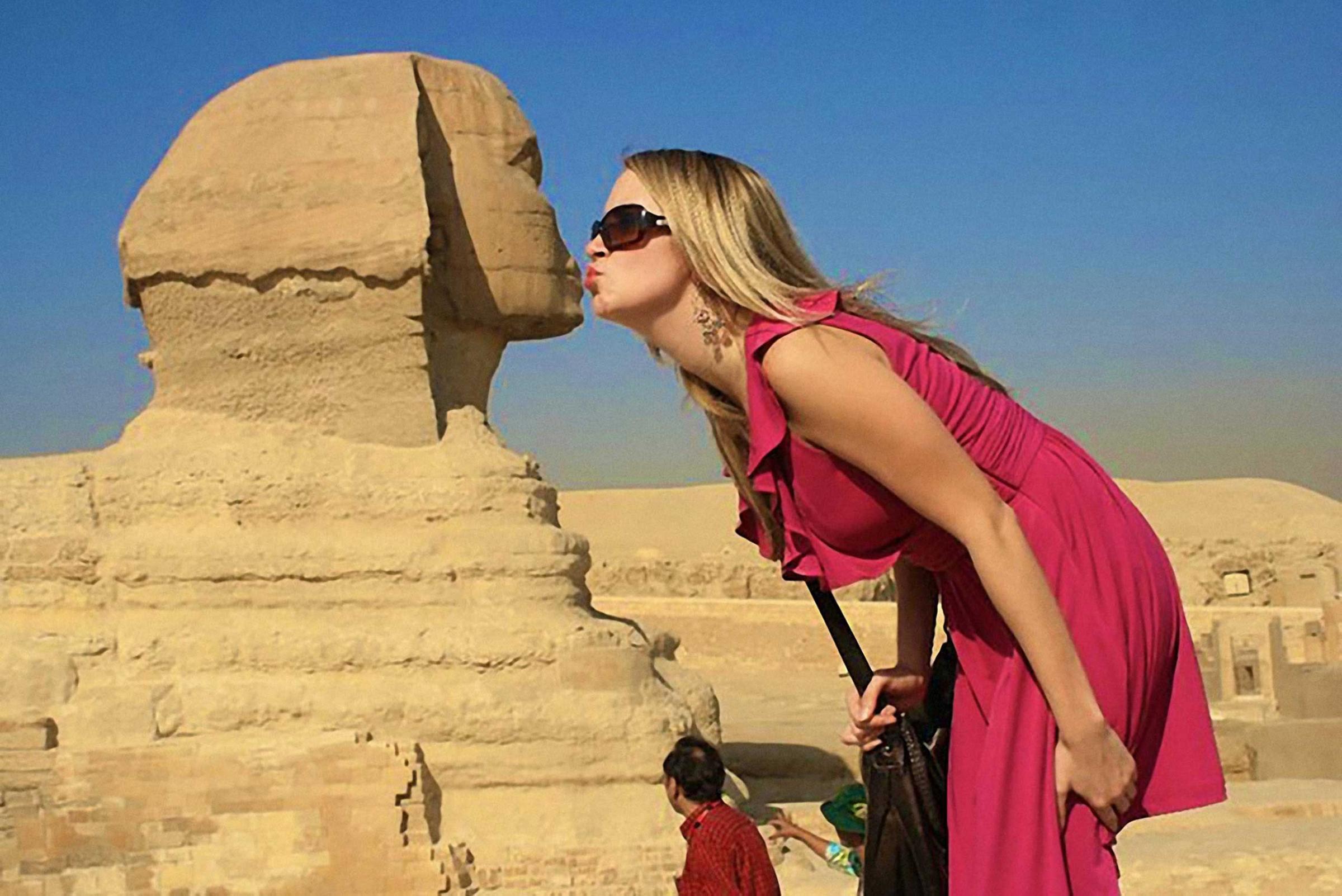

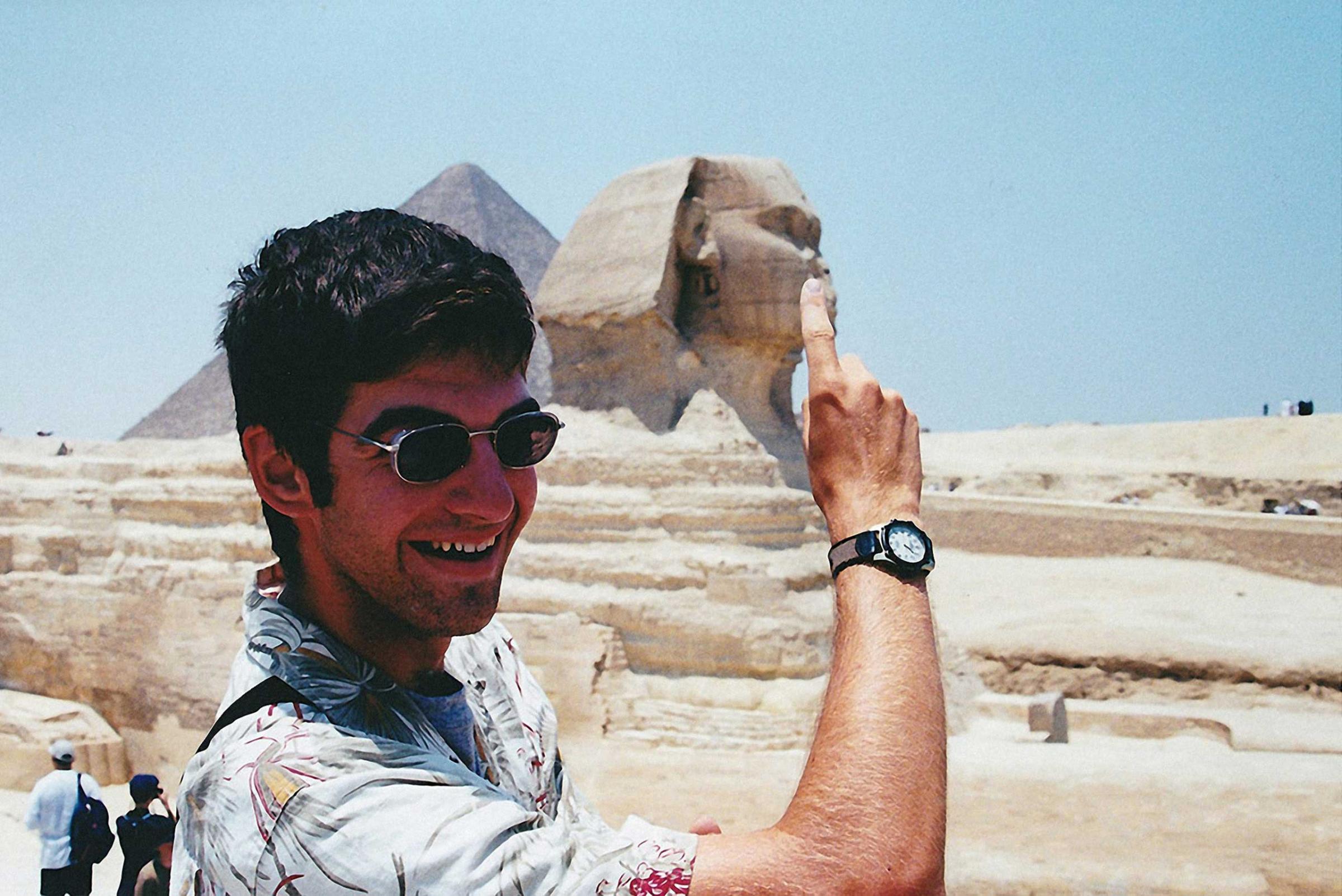

They are one of the Seven Wonders of the World. But for many tourists visiting the Pyramids of Egypt, these ancient marvels are a mere backdrop to the real stars of the show: themselves.

Over the last ten years, tourism photography has increasingly become a vanity project. Rather than documenting spectacular sites, holiday pictures are now used as self-marketing tools to further the narrative of the “ideal life”. They become simply another opportunity to exercise the untamable modern ego – at least that’s what Julien Lombardi thinks. The French artist has documented this complicated relationship in a project called Ego Tour. “I’ve visited a lot of tourist sites across the world – monuments, museums, ruins and the like – and from what I’ve seen, the way the other visitors act is an integral part of the experience,” Lombardi tells TIME.

He used to think that the “meandering crowds and tourism infrastructure” took away from the beauty of the sites but now believes it reflects a deeper connection to foreign lands, our heritage and history.

Lombardi was drawn to the pyramids in particular after an uneasy trip there in 2010. “The pyramids are monumental,” says Lombardi. “But you can’t see them through all the tourist infrastructure. And when I walked right up close – near enough to touch them – they still felt inaccessible amid the throngs of tourists, street peddlers, buses and camels.”

This experience led him to investigate the topic further from a visual perspective. He collected images and produced a video, installations and silkscreen prints, all of which questioned the reality of a site that seemed to be an “authentic fake,” a term used by Umberto Eco, who, with Jean Baudrillard, forged the concept of “hyperreality.”

The project reveals a radical change that has taken place in terms of how these sites are photographed. “The postcard snapshot is no longer the ideal,” says Lombardi. “Tourists are no longer passive bystanders.” In this way, tourism photography has actually returned to its original purpose. “People view photos as visual evidence,” he says. “In the same way that explorers would take photos standing atop a snowy summit or beside a lion carcass.”

But thanks to social media, the “snowy summit” or the “lion carcass” have become so familiar, they are no longer actually seen but reduced instead to a quasi-virtual idea. “Simply gazing at them or using your imagination has become an unfulfilling chore,” Lombardi says. “The poses are a sort of acculturated universal language that reflects a desire to interact with sites in a physical way.” For Lombardi, this is both a worrying and fascinating state of affairs. “The pyramids have been reduced to a symbol, a background for a performance,” he adds.

Both tourists and tourism sites are responsible for this change in attitude. “Tourist sites are now laid out and staged for taking photos, which has become the main attraction,” says Lombardi. “They’ve transformed them into a sort of fun social-media playground for photography.” The advent of selfie sticks and smartphones is another key factor. Lombardi says the most profound change in photographic practice is the “moment when cameras began to turn around to look at their owner rather than the outside world.”

But the democratization of photography could have dangerous consequences, Lombardi says, believing that it is contributing to the “disappearance of reality and ushering in a world where images signify more than what they depict.” This means that our memory is becoming more visual than tangible and our organic relationship with the world around us is slowing decaying. We rely on these tools to navigate our surroundings but they are the very things that separate us from reality. “The image feed produced each day has become unintelligible and soon algorithms alone will be able to make sense of it,” says Lombardi. “I think we need to seize control of this visual material and rethink our habits, to avoid becoming estranged from the world.”

Julien Lombardi is an artist and photographer based in France. View more of his work here.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com