This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

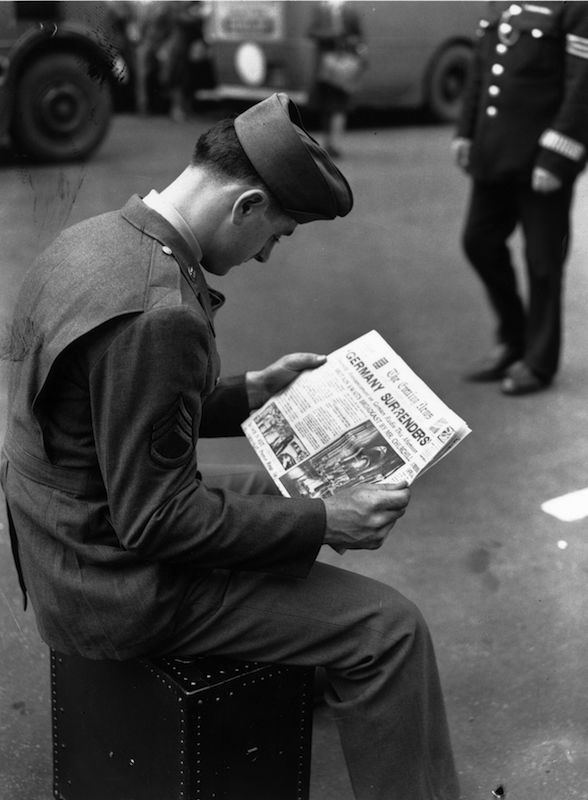

Earlier this week the United States and Europe marked the 72nd anniversary of V-E Day, Victory in Europe, with mostly low-keyed ceremonies and announcements. Today, a date that was of equal or even greater importance for GIs will probably slip by with even less notice. We are referring to May 12, R-Day, for redeployment and readjustment, the day when GIs in Europe and the Pacific Theater learned if they had accumulated enough points to be sent home.

R-Day was the result of nearly two years of planning by the War Department to develop the most equitable means of discharging troops from service. During this process, scientific polling methods were applied to obtain the opinions of representatives from each of the Army’s constituent groups. The response showed that the GIs agreed with Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that discharge by units, such as divisions, as had been the case in the First World War, would be grossly unfair, since each unit had both short-and long-termers and the former would be released while the latter would wait in frustration.

Instead, the Army’s V-E Day demobilization formula would assign the soldier or airman points in various multiples for service rendered as of May 12, 1945. This total was known as the Adjusted Service Rating (ASR). Each month of service earned a point; each month of overseas service was another point. Combat service was recognized by battle stars affixed to a theater ribbon (European or Pacific), each star adding five points. Each medal for merit or valor and the Purple Heart for wounds earned five points as well. Fathers received twelve points each for up to three dependent children.

Initially, a point score of 85 or above would qualify one for discharge. Low score men would stay behind for occupation duty in Germany or be sent through the United States for a 30-day furlough and then on to the Pacific. Construction and engineer units would sail directly for the Pacific with no furlough. Altogether, the Army expected to redeploy three million men to the United States and the Pacific Theater while it discharged another two million by June 1946. Under the best of circumstances, moving large military units was, said a colonel in the Transportation Corps, as “complex as all get out”: “You’ve got a hundred different variables and you’ve got to be able to rationalize all your variables,” and re-rationalize them. General Marshall, who was not given to exaggeration, called redeployment “the greatest administrative and logistical problem in the history of the world.”

The ASR system was in many ways an eminently fair means of discharging veteran troops and identifying those who should be called on to render further service in the Pacific. It was also an administrative nightmare. The program was subject to varying interpretation, misinformation, and error. The awarding of battle stars illustrates the hidden difficulties of what would seem like a straightforward system of honoring combat service. The authorization of battle stars was an ongoing process as points were calculated and divisions slated for the Pacific were cleared of men with over 85 points. The 2nd Division learned just days before it sailed from Europe that it had been awarded two more campaign credits which immediately qualified an additional 2,700 men for discharge. The same problem occurred with the 5th Division, which unexpectedly lost 600 men. Altogether, the belated awarding of stars exempted an additional 14,000 men in the European Theater from further service.

Writing to General Dwight Eisenhower in Europe, Deputy Chief of Staff General Thomas Handy confided that “The headaches about the campaign stars are just getting started.” Handy added that he had already received complaints from men who thought they were getting a “raw deal.” “These all came in,” he continued, “before it was known that there was a payoff on the basis of stars.”

In addition to stimulating a constant churning of manpower within divisions, the point system threatened to strip units of their most experienced personnel and leaders on the eve of the climatic battles with Japan. This was particularly noticeable in the Philippines where the already battle weary divisions of the Sixth Army were seeking to replenish troops lost in securing the islands with raw recruits from the U.S. In addition, these same units scheduled for the first phase of the invasion of Japan were about to lose as many as 23,000 veterans who had accumulated 85 points or more.

Although Marshall had aimed for fairness in the discharge process, he soon found the Army under fire from critics at home who accused the “brass hats” of, among other things, holding on to soldiers for menial tasks like housekeeping and lawn mowing. Senators complained that the discharge process was too cumbersome and should be replaced by a simple first-in-first-out system. Why not lower the discharge age from forty, asked others? The War Department, with Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson taking the lead, refused to break faith with the soldiers by altering the discharge system. Patterson had found the public’s commitment to sacrifice on the home front wanting throughout the war. Now he sensed that public opinion was settling on the prospect of economic reconversion and the loosening of wartime restraints. He dug in his heels and repeatedly rejected calls by the heads of civilian agencies to furlough soldiers needed for railroad work, mining, and other industries in need of skilled labor. “Bob Patterson not only has a one track mind,” complained Solid Fuels administrator Harold Ickes, “the one track is just a short spur.”

By July, the Army was struggling to organize, train, and redeploy troops needed for the invasion. Young draftees were being sent to replace soldiers lost in the battles in the Philippines and on Okinawa and to fill in for men with high points who were headed home. The pressure on shipping in both directions created by the simultaneous operation of both processes, redeployment and discharge, mounted. Admiral Chester Nimitz doubted the Army would be ready for the invasion scheduled for November 1. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest King also saw little chance of alleviating the shortage and unhelpfully reminded General Marshall that there was an increase in the need for shipping in the Pacific “because of the system of point discharges.”

In some ways, the Army was a victim of its own attempt to placate public opinion. Despite the Army’s efforts to prepare Americans for the long hard campaigns still to be fought in the Pacific, the announcement of the beginning of demobilization so soon after V-E Day shifted the American public’s focus from Europe not to Asia but to the home front and economic reconversion. Moreover, the discharge system, with the announcement of the critical score needed for release from service, created an incentive in the wrong direction – home – at a time when most GIs would be learning that their ultimate destination was the Pacific and the invasion of Japan’s home islands. The Army had taken on too much, harboring too many contradictions: organizing the occupation of Germany, shaping up the Sixth Army for the invasion, redeploying millions to the Pacific, all while beginning the process of demobilization. There was still time to remedy the situation, but the clock was ticking. And the enemy, in greater than expected numbers, waited on Kyushu.

Waldo Heinrichs is Dwight E. Stanford Professor Emeritus at Sand Diego State University. Marc Gallicchio is professor of History at Villanova University. They are the authors of Implacable Foes: War in the Pacific, 1944-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com