As tensions between the U.S. and Iran increase, President Trump on Thursday went so far as to accuse former Secretary of State John Kerry of talking to Iranian officials behind his back. The President said at a press conference that he believes Kerry has violated the Logan Act — even though Kerry’s spokesperson has said that the former diplomat hasn’t talked to Iran officials at all since the U.S. pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal last year.

The Logan Act, once an obscure law, has been on the minds of Washington observers since Trump’s former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn resigned on Feb. 13, 2017, after admitting to speaking with Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. about sanctions.

The law prohibits unauthorized U.S. citizens — which Flynn was at the time — from speaking to foreign governments about that country’s “disputes or controversies with the United States.” And the history behind the law sheds light on why it is against the law for individuals to try to influence foreign relations.

The story goes back to the late 18th century, when the French Revolution was in full swing. France and Britain were fighting, and the new nation of the United States was divided about its allegiances. France thought American ratification of Jay’s Treaty — an unpopular peace accord with Britain — violated the past treaties between France and the U.S. Within the American government, Democratic-Republicans like Thomas Jefferson tended to favor supporting France, which had supported the American Revolution. Meanwhile, Federalists like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams argued strongly against getting involved.

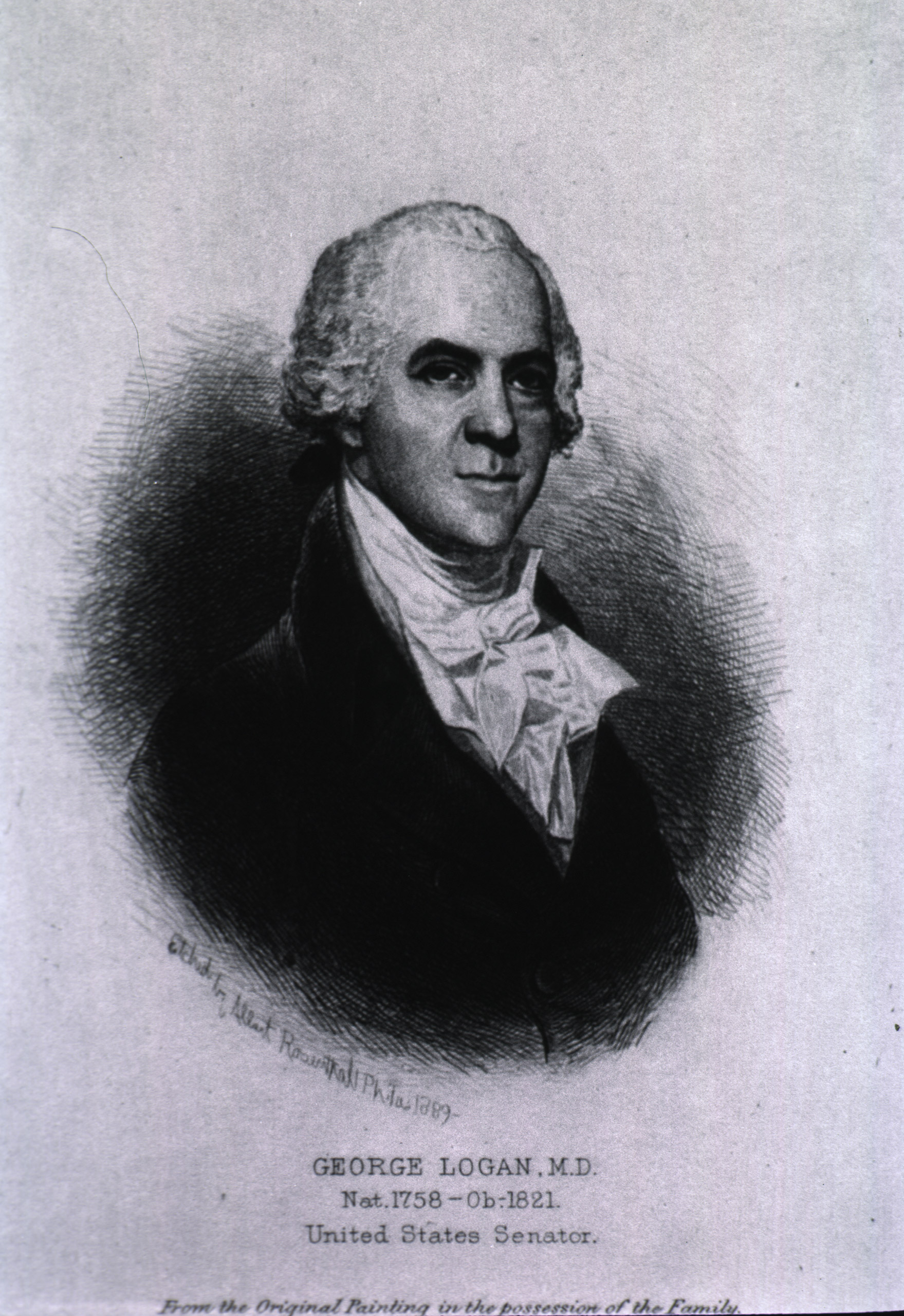

After the diplomatic failure known as the XYZ Affair — a 1797 episode in which French treatment of U.S. envoys shocked the nation, nearly leading to war between the U.S. and France — George Logan, a Pennsylvania state legislator and farmer from a prominent Philadelphia family, decided to step in.

In 1947, after former Vice President Henry Wallace’s “gabbiness” on a trip abroad raised eyebrows, TIME took a look back at what Logan did:

Logan was an 18th Century gentleman farmer, an author of pamphlets on crops and soil, and a Quaker pacifist. He lived on a 500-acre estate near Germantown, Pa., dabbled in medicine, and habitually wore homespun clothes to encourage domestic manufacture. In 1798, Logan saw the U.S., attacked and insulted, preparing for war. French warships had seized U.S. vessels. The French foreign minister, Talleyrand, had cynically tried to exact what amounted to a tribute from the infant country. Nevertheless, Quaker Logan viewed U.S. intentions with consternation, and as a self-appointed peacemaker sailed for France.

He came back with the report that the French Directory only wanted peace, the chief effect of which was to soften American public opinion at the very moment when the Government was trying its best to appear strong. Congress was incensed. The well-meaning Logan got no more than a tongue-lashing, but Congress passed the Logan Act as a curb on all future self-appointed spokesmen.

The act made it a high misdemeanor for a U.S. citizen, without permission from the Government, to carry on any “verbal or written correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with an intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the Government of the United States…”

In other words, even though his mission was relatively successful at achieving his own personal goals, his goals were not the same ones shared by the government — and, as an individual, even a powerful one who was friends with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, he couldn’t have known what was going on behind the scenes. Logan’s intervention showed those in power in 1799 that they had to prevent citizens, no matter who, from taking foreign relations into their own hands.

“He had a great friendship with Thomas Jefferson and shared a lot of his views, so when he sees efforts by Federalists fail through the XYZ Affair, he decides to try and solve this problem, to smooth things over, knowing he had connections in France,” says Dennis S. Pickeral, Executive Director of Stenton, Logan’s historic Philadelphia home. “He does diffuse a lot of the tension, but enrages Federalists, who push through that law.”

Though some have argued that the Logan Act raises issues in the way it constrains citizens’ freedom of speech and right to travel, the concept behind it has stood the test of centuries.

“The Logan Act wanted one President at a time,” says Richard Painter, who was chief ethics lawyer for President George W. Bush and now teaches at the University of Minnesota Law School. “There is one foreign policy conducted by the Secretary of State, whom the President picks and the U.S. Senate confirms.”

There have been no prosecutions under the act since the second President John Adams signed it into law in 1799, according to a March 2015 Congressional Research Report.

But, says Robert Roberts, author of White House Ethics: The History of the Politics of Conflict of Interest Regulation, that doesn’t mean the law is pointless. People who are questioned about their activities in ways that may or may not involve the Logan Act can end up in violation of the False Statements Act, for example.

“In other words, it is highly unlikely anyone will be prosecuted for violations of the Logan Act,” Roberts says. “It is much more likely someone will be prosecuted for lying to the FBI.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com