As postmortems on the 2016 election continue to roll in, one particular piece of exit-poll data has surprised many commentators: given the chance to vote for Hillary Clinton, the first woman to be the presidential nominee for a major American political party, many women passed it up. As highlighted by the New York Times and CNN, the overall female vote was split between the candidates, with white women going for Donald Trump at more than 50%. The data suggest that one of the many things that pollsters got so wrong in predicting a victory for Clinton was that they assumed women would vote as a bloc.

For example, Brent Budowsky in an article for the New York Observer predicted that “women will vote en masse against Trump,” after the Republican candidate’s sexist comments became the October surprise that dogged the Republican nominee during the final weeks of the campaign. Budowsky and many others were certain that “the female turnout [would] soar on Election Day,” handing the presidency to Clinton. But such predictions ignore historical precedent and indulge in what New York Times writer Amanda Hess has called “The Dream—and the Myth—of the ‘Women’s Vote.”

Hess’ article traces the idea of women as a voting bloc to the early days of the suffragist movement, when in 1870 Victoria Woodhull announced her candidacy for president even though the disenfranchisement of women would prevent her from voting for herself. The New York Herald gleefully championed her candidacy and women’s suffrage, imagining that Woodhull would be poised to make history because “women always take the part of each other.” Susan B. Anthony concurred, echoing sentiments expressed in the 1850s that women were the nation’s moral compass and that with the franchise women would speak with one voice thus ridding the nation of its social evils.

But, Woodhull’s support among suffragists soon fractured due to a sex scandal. With her reputation sullied, she could not hope to “secure the feminine vote.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Yet even amid the excitement over Woodhull’s run, black female suffragist Frances E. W. Harper—aware that the category of “women” as defined in American society was underscored by the politics of race and class—rejected the notion of women as moral compass. She stated the point in an 1893 speech titled Women’s Political Future: “I am not sure that women are naturally so much better than men that they will clear the stream by the virtue of their womanhood.” Historian Paula Giddings has noted in her classic book When and Where I Enter that during the struggle leading up to the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which would grant black men the franchise, if only temporarily in practice, Harper rejected Anthony’s arguments that black women should support the suffrage of white women over black men. “White women all go for sex, letting race occupy a minor position,” she wrote. “Being Black means that every white, including every white working class woman, can discriminate against you.”

But there were also factions among white female suffragists. As historian Anne Boylan observed in her book Women’s Rights in the United States, members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) disagreed about which women should be enfranchised and debated what should be the organization’s political platform.

Southern suffragist Belle Kearney of Mississippi argued in a speech before the NAWSA in 1903 that the goal of women’s suffrage should be to maintain white supremacy stating, “The enfranchisement of women would insure an immediate and durable white supremacy honestly attained. . . the enfranchisement of women would settle the race question in politics.” Yet, many white elite southern women such as Mildred Rutherford of The United Daughters of the Confederacy opposed women’s suffrage for fear that black women would gain the franchise; she also believed that men were better suited to “legislate for women.”

Women not only varied in their support of women’s suffrage, they have also varied in their support of female candidates.

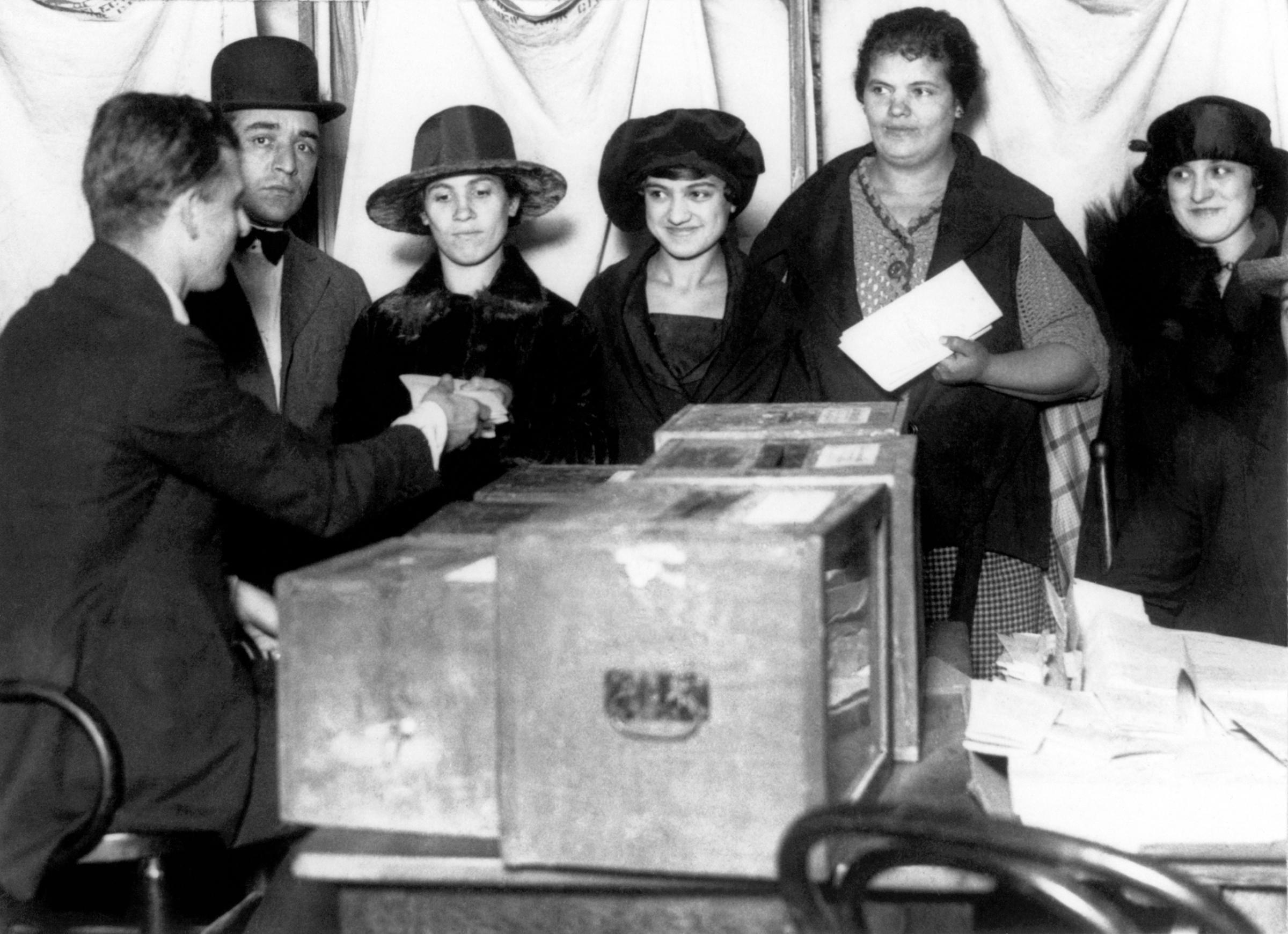

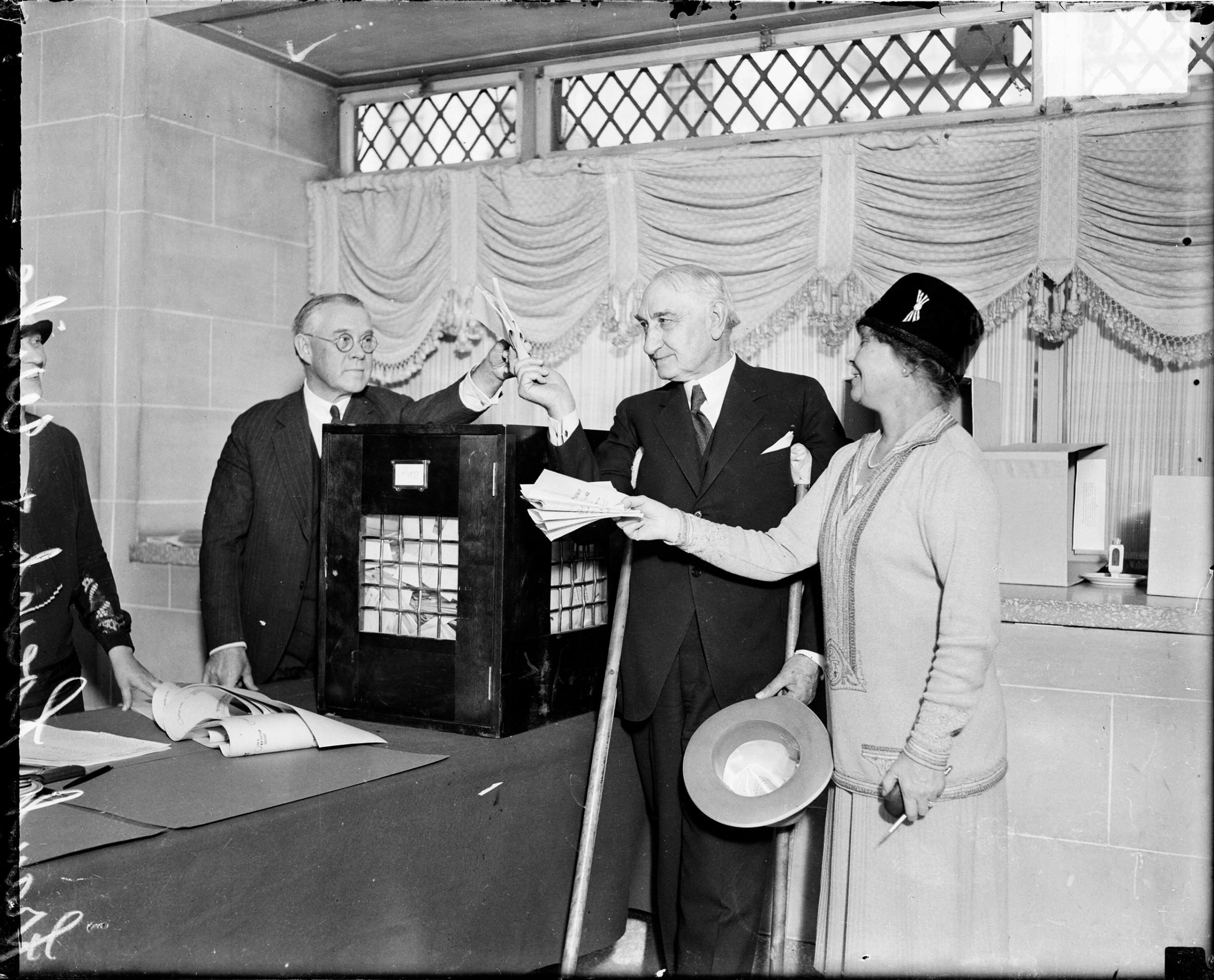

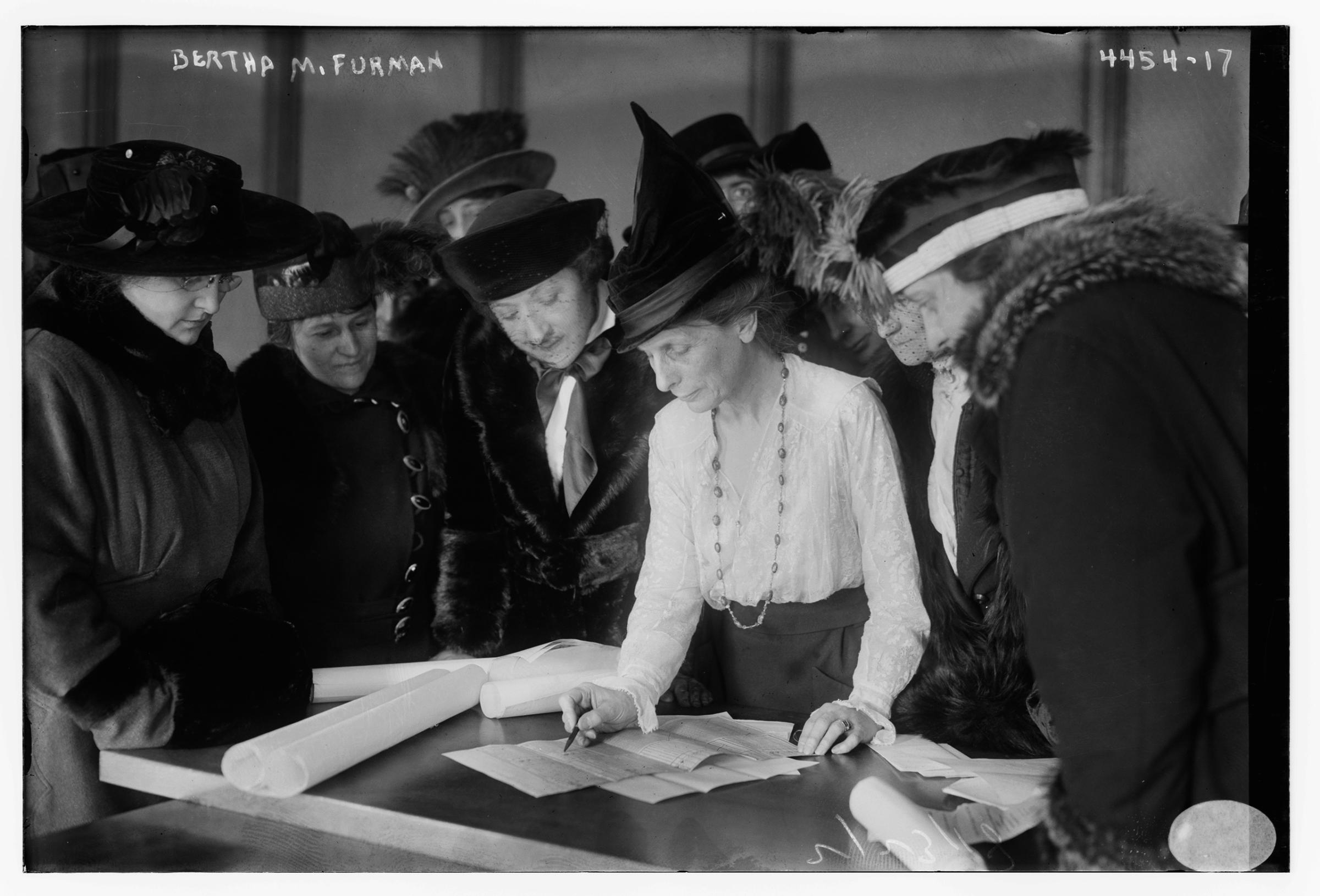

See Vintage Pictures of Female Voters in the Early Years of Suffrage

![1924Prominent Republican women call on Pres. to discuss the part of women will play in the coming election. Lft to rt.: Miss Lucille Atcherson, State Dept., Mrs. B.P. Bruggmann, US Compensation Comm., Miss Mabel W. Willebrandt, Asst. Atty. Gen.; Mrs. Mary Anderson, Chmn., Woman's Bur., Labor Dept.; Miss Anne Webster, Chmn. Nat'l League of Women Voters; Miss Julia Lathrop, 1st Vice-Chmn., Nat'l League Women Voters; Miss Grace Abbott, Head Children's Bur., Labor Dept. [White House, Washington, D.C.]](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/44268u.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Governor an "early bird"--Mr. and Mrs. Smith voted at Public School No. 3, Oliver and Henry Street [between 1919 and 1928]](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/3c17793u.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Kate Walbert’s New Yorker article Has Anything Changed for Female Politicians? notes the career of Montana Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin, who became the first woman elected to Congress in 1916. She was blamed for her male opponent’s suicide, on the idea that he lost the will to live once he learned he had been defeated by a woman. Although she had formerly served as secretary for the NAWSA, her political breakthrough was greeted with contempt from colleague Carrie Chapman Catt, NASWA President, who complained, “the first woman in office should be an ‘intellectual’—certainly not a Westerner without a law degree.”

And perhaps the clearest example that women don’t vote as a bloc came in 1984, when New York Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro—who had a law degree, just as Catt hoped—made her historic run as Walter Mondale’s Vice President. The ticket’s only Electoral College votes came from the District of Columbia, with Ronald Reagan winning 54% of the national female vote.

Catt’s elitism notwithstanding, Naomi Klein suggested something similar to her 1916 logic in a recent New York Times article, making the argument that Clinton’s defeat seems less to do with sexism and misogyny and more to do with the candidate herself. Her headline—“Trump Defeated Clinton, Not Women”—both challenges the myth of Clinton as the embodiment of women and the idea of women as a monolith.

Indeed, the dream of a woman president is surely not dead, but rather deferred. Let this election serve as a teachable moment for the nation and as a cautionary tale to the next woman nominee for president.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com