The predictions were wrong last week, when Donald Trump upset expectations with an Electoral College victory in the U.S. presidential election. In addition to the many questions observers were left asking about a Trump administration, an eventuality for which few had prepared given the polls in favor of his opponent Hillary Clinton, the polls themselves came up for an examination. How did they miss it? And why did the world think they could get it right in the first place?

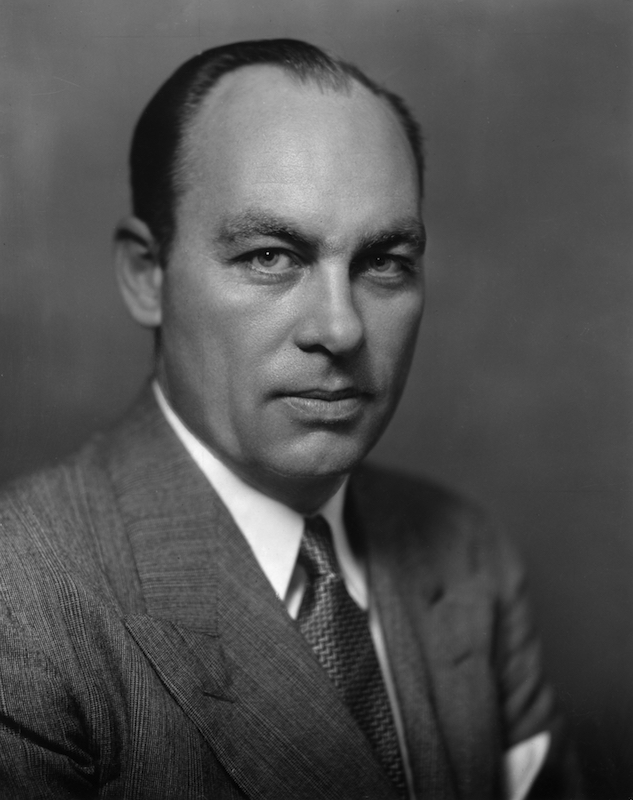

One answer to that second question can be found in the biography of a man born 115 years ago Friday: George Gallup, the man behind the Gallup Poll.

In a May 1948 cover story, TIME dubbed him the “Babe Ruth of the polling profession”—not the only or the first pollster, but the most famous and the one who defined the game, and in doing so changed the history of American politics.

Gallup’s personal road to political polling had, as TIME explained back then, a certain winding air to it—but it was driven, all along, by his faith in numbers and the desire to measure the world. As a friend of his told the magazine, he wished he had invented the ruler. Raised in an eccentric Iowa family and having to pay his own way through the State University of Iowa, he ended up editing the Daily Iowan. He developed an interest in figuring out who was actually reading the paper, and which parts they liked best. “At that time, a common way of measuring reader interest was to yank out the crossword puzzle for a week and count the complaints,” the magazine noted. “Gallup adopted the startling device of confronting a reader with the whole newspaper and asking him exactly what he liked and didn’t like about it.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

He turned that research into a Ph.D. and, then, into paid work for several newspapers and a prestigious advertising-industry job. In 1932, with a presidential election approaching, he decided to see if he could use his ad-testing ideas to assess the state of politics, TIME explained:

He talked the idea over with a blond, blue-eyed Midwestern salesman of newspaper features named Harold Anderson, who had become a partner in Gallup’s research service. Anderson jumped at it, urged Gallup on. He began lining up newspaper publishers, soon interested both the Washington Post‘s Eugene Meyer and the New York Herald Tribune‘s Helen Rogers Reid.

After three years of practice, Gallup had assured himself that polls on toothpaste and politics were one & the same. He was also convinced that the famed Literary Digest poll was heading for a disastrous cropper. The millions of Digest postcards were mailed on the basis of telephone and auto registration lists and took no account of the low-income voters who had swung solidly behind the New Deal.

Not long after the first Gallup Poll appeared, Gallup brashly announced that the Digest would be wrong in the 1936 election, followed that up with a prediction that the Digest, by its methods, was bound to pick Landon by 56%.

On election night, 1936, Gallup flipped on the radio and knew he was in. Though he had badly underestimated Roosevelt’s winning margin, he had called the Digest’s predictions within 1%. After that, it was simply a question of convincing newspaper publishers that there was still news for pollsters to report.

By 1948, the Gallup Poll organization—officially called the American Institute of Public Opinion—operated in a dozen countries, influencing everything from the titles of Hollywood movies to Book-of-the-Month Club picks, in addition to its political predictions. By its sheer omnipresence (the Gallup Poll released data to newspapers a whopping four days a week) Gallup became synonymous with polling.

And, with a Gallup poll readily available, the American media and public came to expect that elections—and so much else—could be correctly predicted.

Gallup’s faith in numbers allowed him to break down the U.S. electorate into a precise set of demographic groups, which he then represented proportionally in his sample group of 3,000 people. But even then, some of the obstacles confronted by pollsters today held true: high voter turnout had helped Democratic tickets ever since the New Deal, so calculating the likelihood of voters showing up—and their relative Electoral College weight—made politics more complicated than the other topics Gallup tackled.

And sure enough, mere months after that TIME cover story came out, Gallup and the rest of the country saw just how complicated it could get. That year’s election produced the most famous—well, perhaps now the second most famous—polling error in American political history: President Harry S. Truman’s victory over Thomas Dewey. Gallup and his fellow pollsters had predicted just the opposite. TIME reported that Gallup, even as he put some blame on the margin of error, sent his interviewers out to talk to the same people they had spoken to before the election, to see where they went wrong.

But, much as the U.S. might swear in 1948 that no pollster would ever again be trusted, it was too late for that.

“The argument over whether public-opinion polls are good or bad for a democracy has become somewhat academic —they are obviously here to stay,” TIME had noted earlier that year, in the cover story. “They can find out what the people, who rule a democracy, think and want. But a democracy also needs leadership by men who must frequently tell the people why a popular notion—no matter how widely held—can be wrong.”

When Gallup died in 1984, at age 82, TIME assessed his legacy thus: he may not have always been right, but his attempt to measure what Americans wanted permanently changed the nation’s political systems. Decades later, the argument still holds.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com