This year has become the deadliest on record for migrants crossing the Mediterranean for a better life in Europe, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), despite an overall decrease in the number of people making the crossing compared to 2015.

In a tweet issued on Wednesday, the humanitarian agency said more than 3,800 migrants were dead and missing. The figure already exceeds the 3,771 migrants’ lives lost on the Mediterranean for the whole of 2015—a little more than two months before the end of 2016.

“This is the worst we have ever seen” UNHCR spokesperson William Spindler told reporters on Tuesday, when the agency first announced their alarm at the rocketing death toll. The likelihood of dying is the highest in the Central Mediterranean Route, said Spindler, where around half of the Mediterranean crossings this year came from the perilous route between North Africa and Italy. The route’s vast distance, unpredictable weather and strong currents makes it almost impossible for an overloaded boat to make it from Libya to the southern coast of Italy.

Libya has long been a launching pad for migrants attempting to reach Europe, but not in the numbers seen in the past few years (of 150,000 in 2015 compared to 64,000 in 2011). The toppling of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi and the country’s ensuing power vacuum has also allowed for smuggling networks to bloom into an industry estimated to be worth $5 billion to $6 billion annually. The closure of the E.U.-Turkey route in March might have lowered peak numbers seen in 2015, but increased conflict or hardship in countries such as Somalia, Ethiopia and Nigeria have compelled migrants to embark on the dangerous crossing.

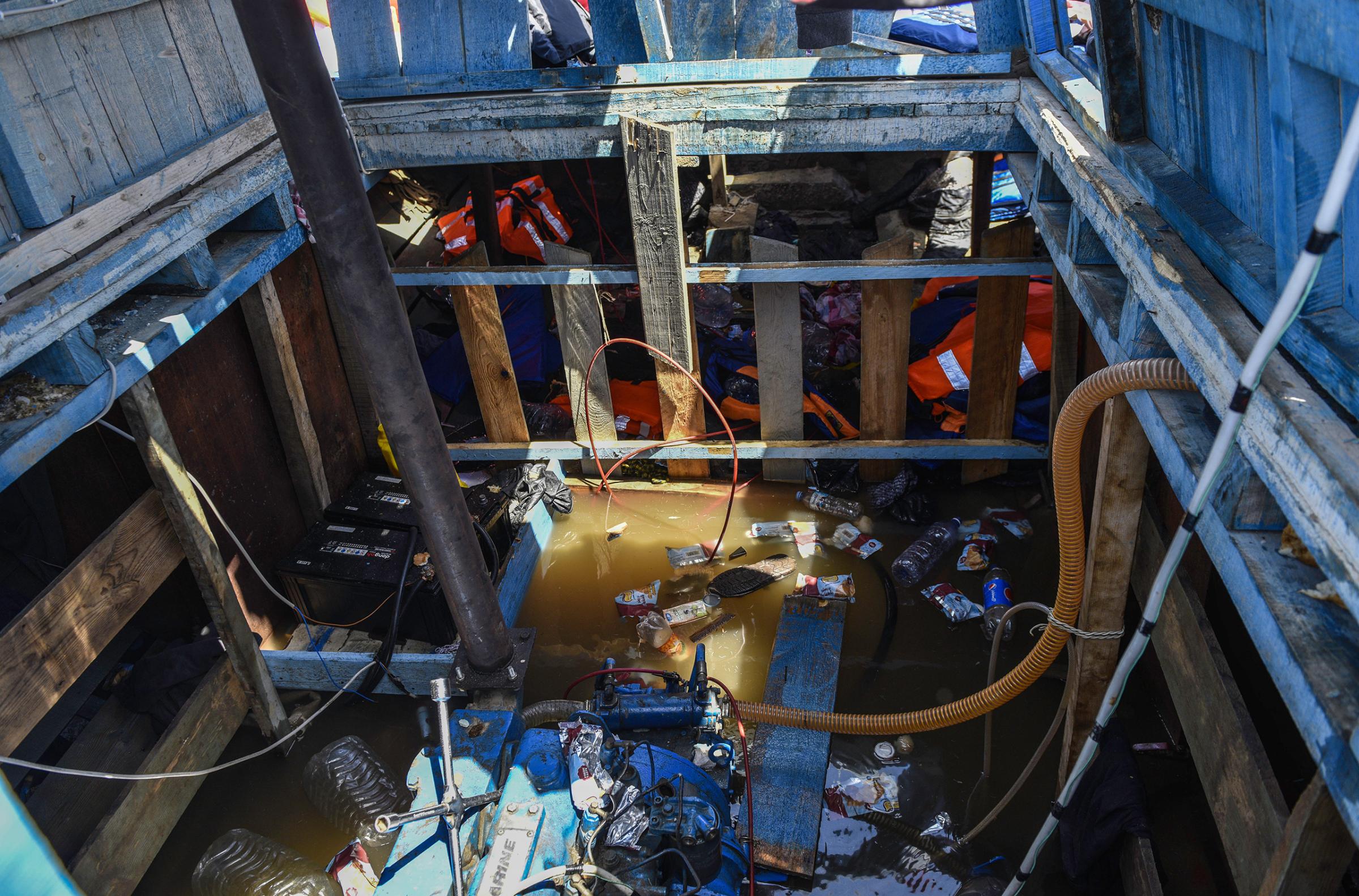

Spindler said that the route is now seeing the “mass embarkations of thousands of people” at a time, a new tactic by the smugglers that might be “geared towards lowering detection risks” or a shift in their business model. This might be in response to the E.U. launching Operation Sophia in 2015. According to the Economist, the military operation’s mission was to reduce crossings by destroying suspected smuggling vessels close to the Libyan coast. With their wooden boats destroyed, the smugglers sent migrants off on flimsy, cheap and low quality rubber dinghies.

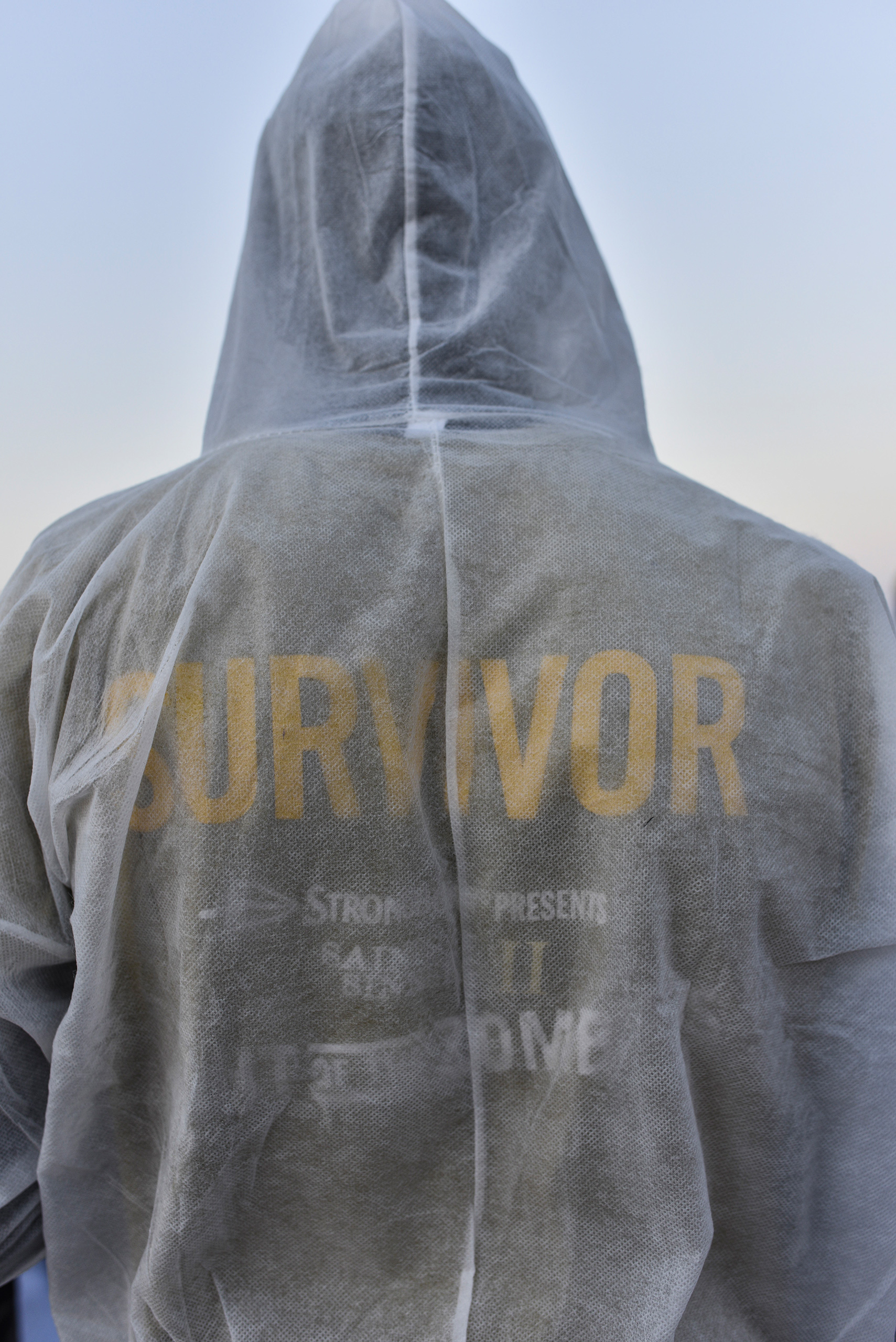

Migrants’ Last Hope: A Rescue on the Mediterranean Sea

Dinghies might also be a cynical move by smugglers, who are aware that they have a chance of being picked up by European vessels—be it navies or chartered rescue ship. “They are setting out in boats that are designed to sink,” Federico Soda, director of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Coordination Office for the Mediterranean, told TIME in September. “They would all die if there wasn’t someone to help them at some point.”

Rescue services are also overstretched and struggling to cope with the deluge of migrants. Earlier in October, the Italian Navy and Coast Guard rescued 6,000 migrants in a single day, reports the New York Times, and saved 2,200 on Monday during 21 rescue operations. “This high death rate is also a reminder of the importance of continuing and robust search and rescue capacities–without which the fatality rates would almost certainly be higher” Spindler said.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com