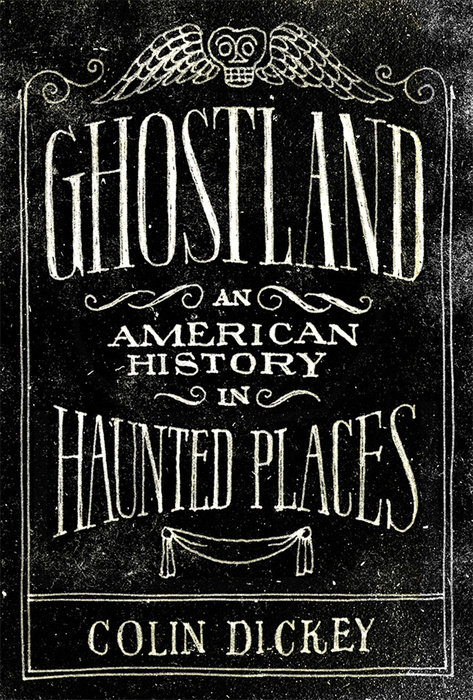

The U.S. may be a relatively young country, but it has its fair share of ghost stories and haunted houses. And according to Colin Dickey, author of Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, most of those myths tells us something about our society’s fears and anxieties.

Dickey toured America’s most famously creepy buildings to research his book, and found that people often use “the language of ghosts and the language of hauntings to get at other aspects of culture in American society,” he tells TIME. “When there’s something curious that doesn’t belong, that nobody has an explanation for, the language of ghosts becomes a way of giving that place a sense of history.”

Take the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, Calif., the residence of the widow Sarah Winchester. Sarah married into the Winchester Rifle Company family and lost both an infant and her husband early in her marriage. Legend has it she became convinced her house was haunted by everyone ever killed with a Winchester rifle, and her house became an unfinished project of complicated architecture meant to keep those spirits at bay, based on advice she received from a psychic.

When Dickey looked into it, he found that a lot of the so-called legend was actually true. But he also found that the part people tend to focus on—her idea that the house was haunted—was not the most significant element of the story.

“Here was a woman who was living alone, who never remarried and thus was living outside of the cultural norm of what would be expected of her particularly in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. This figure of a kind of anomalous spinster who didn’t go out as much, who had a lot of wealth but spent it somewhat idiosyncratically—these are the kind of factors that will often feed a ghost story,” he says. “I think a story like that often reflects more of our attitudes about single women, towards the wealthy, and in Sarah Winchester’s case our attitudes towards our anxiety about guns and the ‘winning of the west.’”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

A similar Freudian displacement takes place at Lemp Mansion in St. Louis, home to a German-American family whose beer brand, Falstaff, was a rival to Pabst and Anheuser-Busch. After a series of financial and personal setbacks in the early 20th century, several members of the family committed suicide—leading onlookers to believe the house must have been haunted by spirits that drove them to their deaths.

“From the non-paranormal perspective,” Dickey says, “here is a family that may very well have been suffering from undiagnosed depression or other medical ailments that went untreated. It manifested itself in this way that people seize upon for its supernatural aspect as a way of sidestepping these concerns about depression and mental health.”

Though Dickey also writes about hotels, abandoned asylums and prisons that are rumored to have spirits hanging about, houses are the focus for a reason.

“The home represents safety, it symbolizes achieving the American dream, it symbolizes wealth and affluence,” Dickey says. “And so the haunted house is kind of the inversion of all that. It’s the place that should be safe and welcoming and warm, but it’s become scary and terrifying. It’s become uncanny in the literal German sense of the word, which is unheimlich, or unhomely, not home-like.”

Ghostland approaches phantoms as metaphors for what ails our society, but of course many people actually believe that ghosts are real—polling hovers around a third of Americans who say they believe. But Dickey pleads the Fifth on his own belief.

“What I realized really early on,” he says, “is that if somebody believes in ghosts and you try to disprove that to them, it’s not going to work.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com