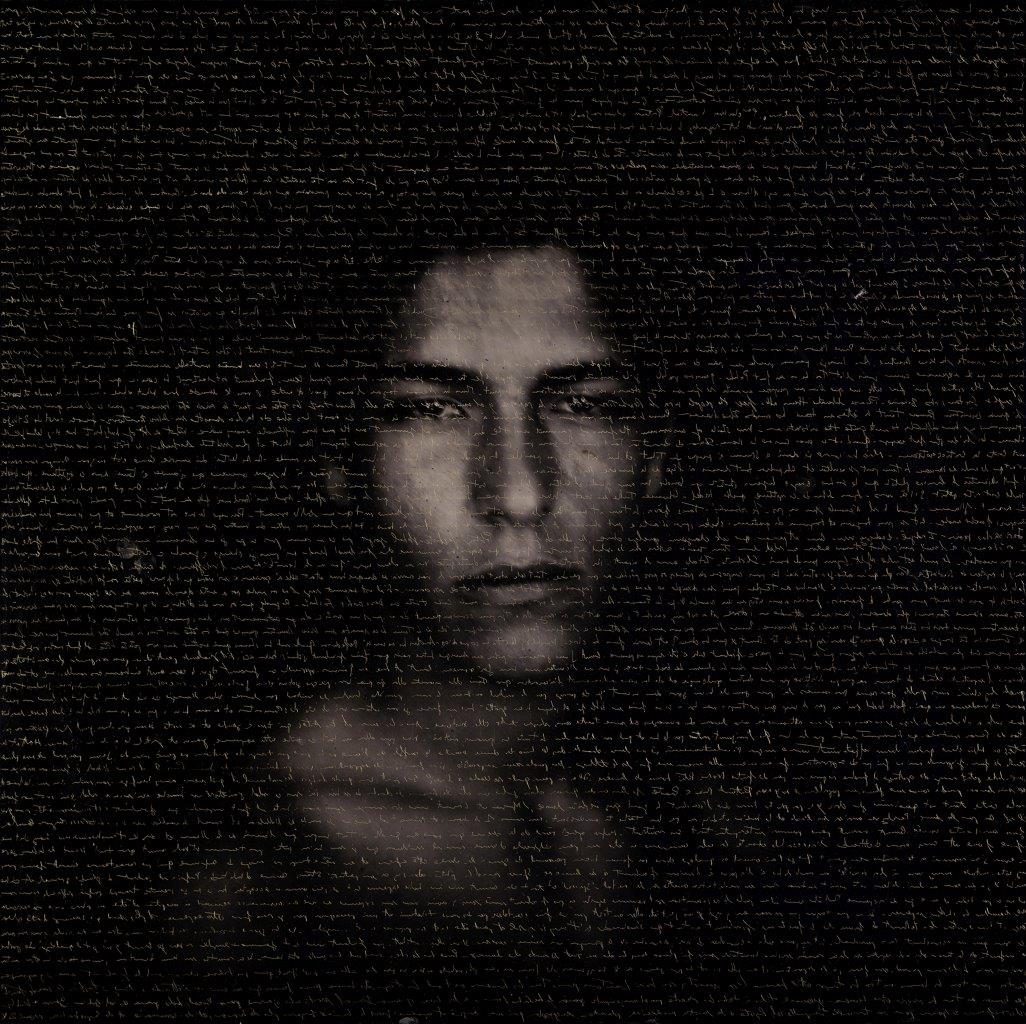

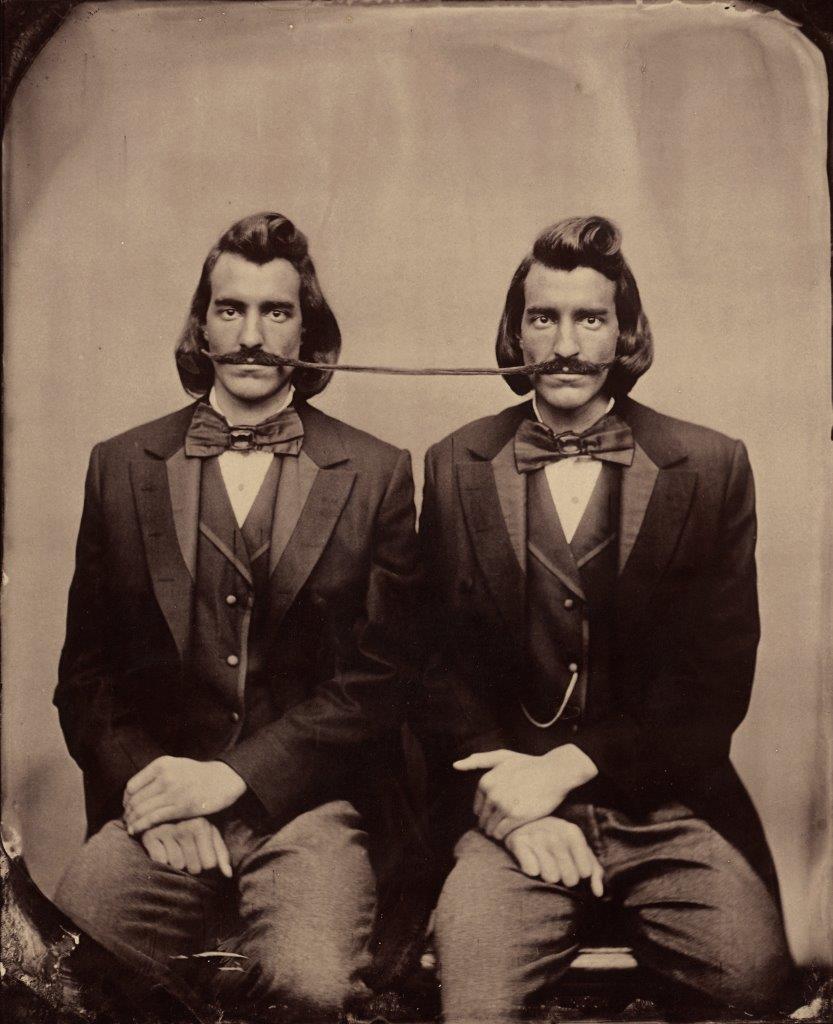

“When you look at a 19th century portrait, there is a palpable sense of the person actually being there in the image,” photographer Jerry Spagnoli tells TIME. “It’s still an image. It’s in your hand. But the daguerreotype is so persuasive that you can actually suspend your disbelief and feel like you’re looking at the person because of that sense of values in the image.” The first time Spagnoli saw a perfectly preserved daguerreotype, he says he was amazed by the “presence of it.” The early photographic process, in which photographs are printed on a polished silver plate, captured something “essential about photography,” he says.

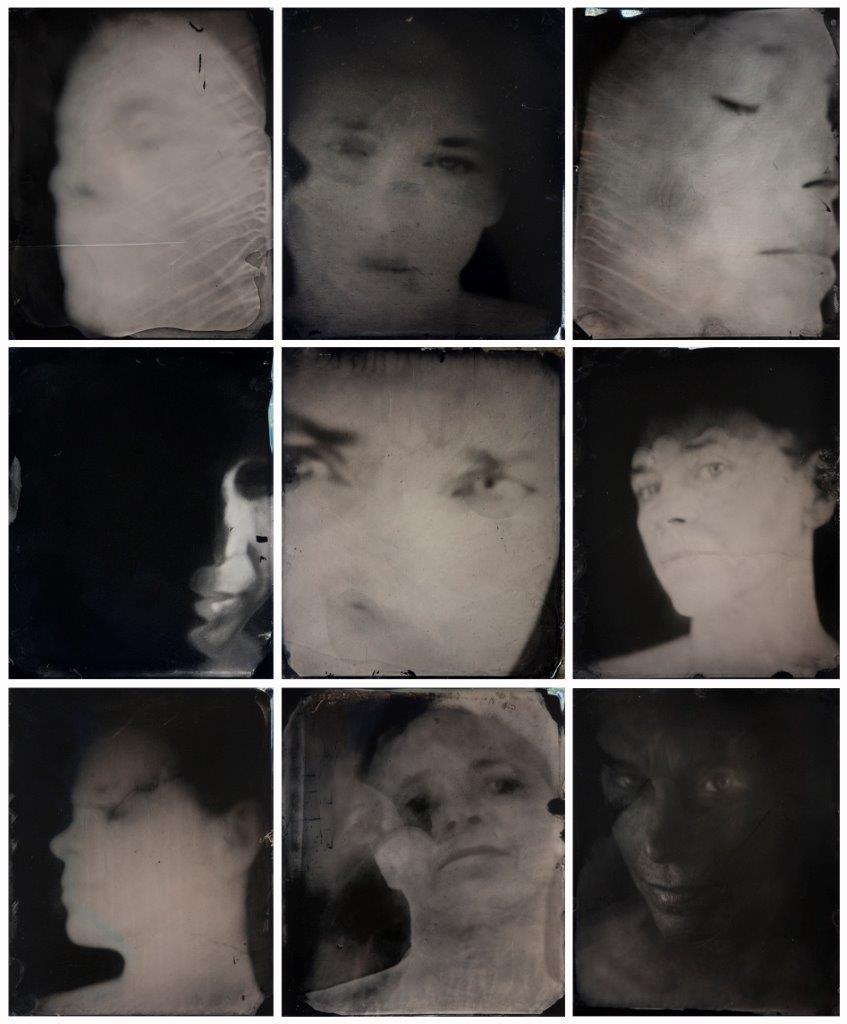

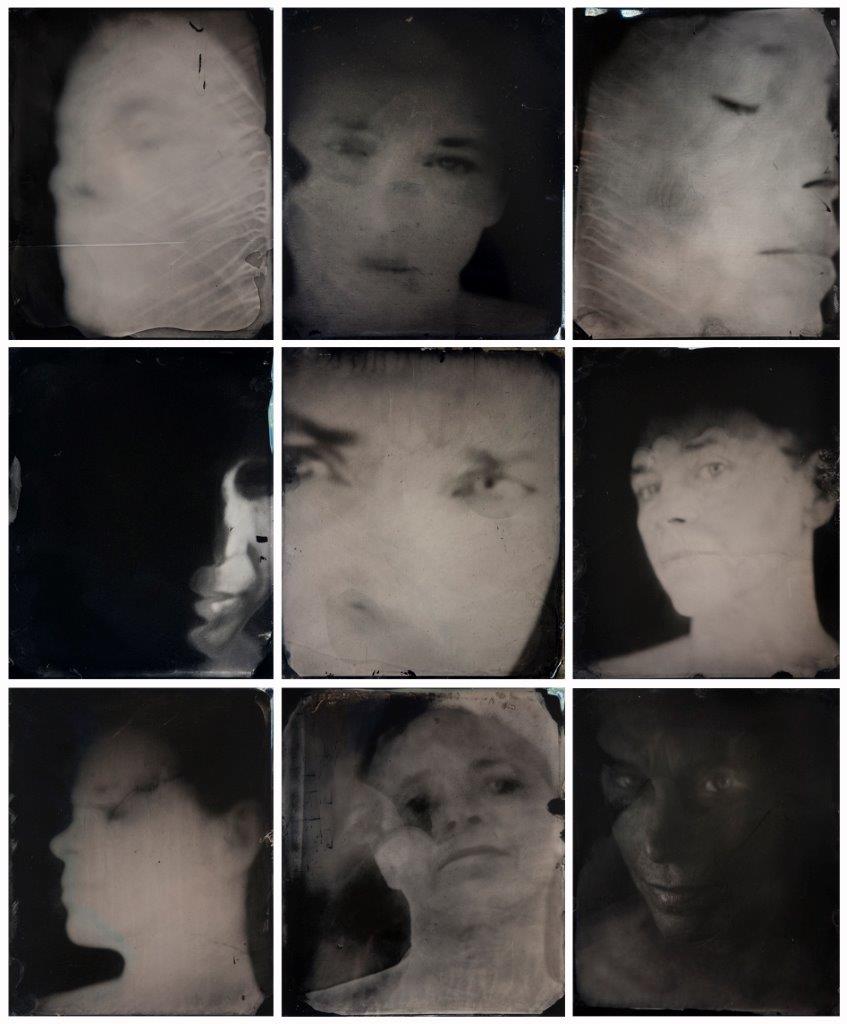

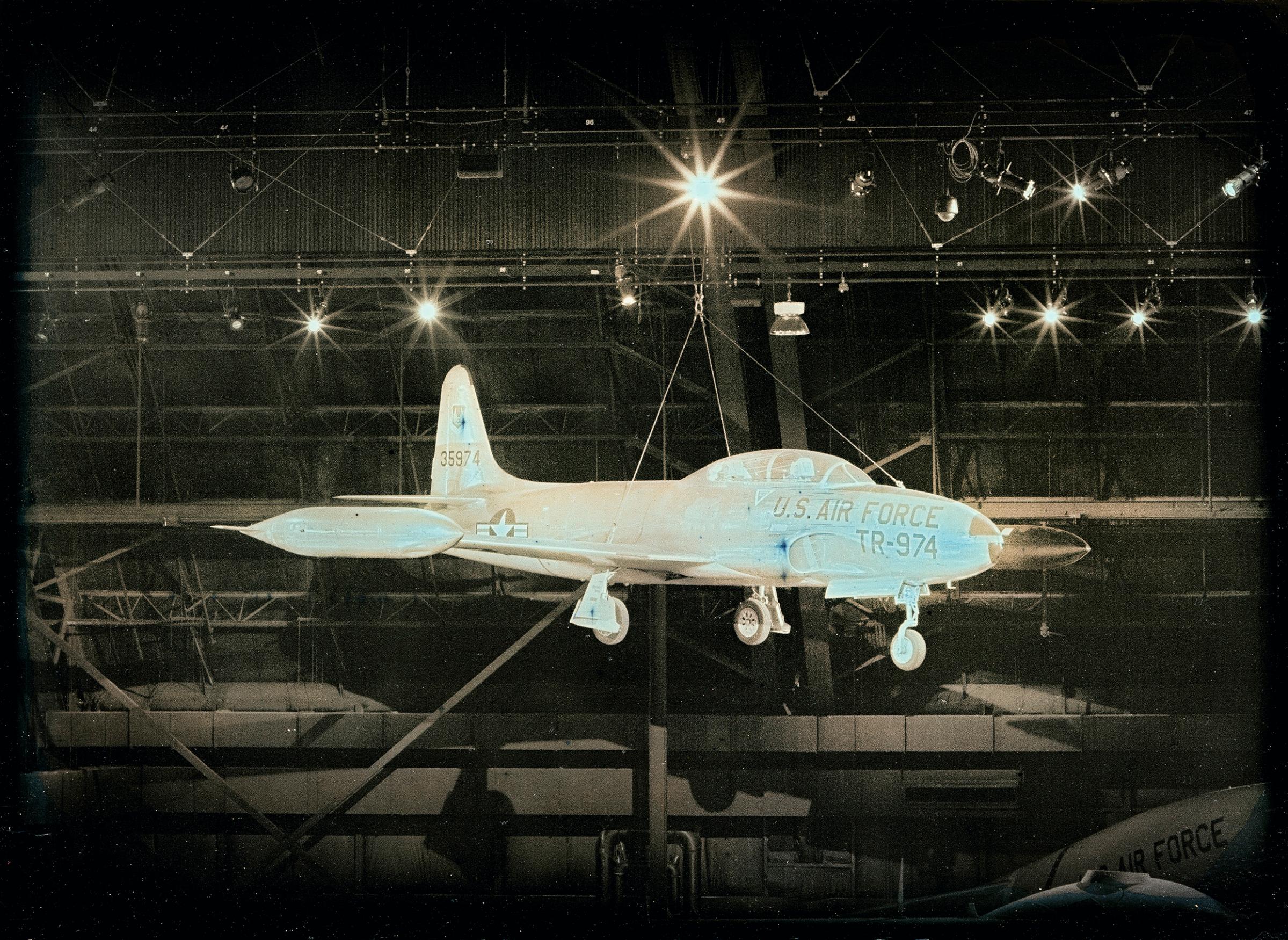

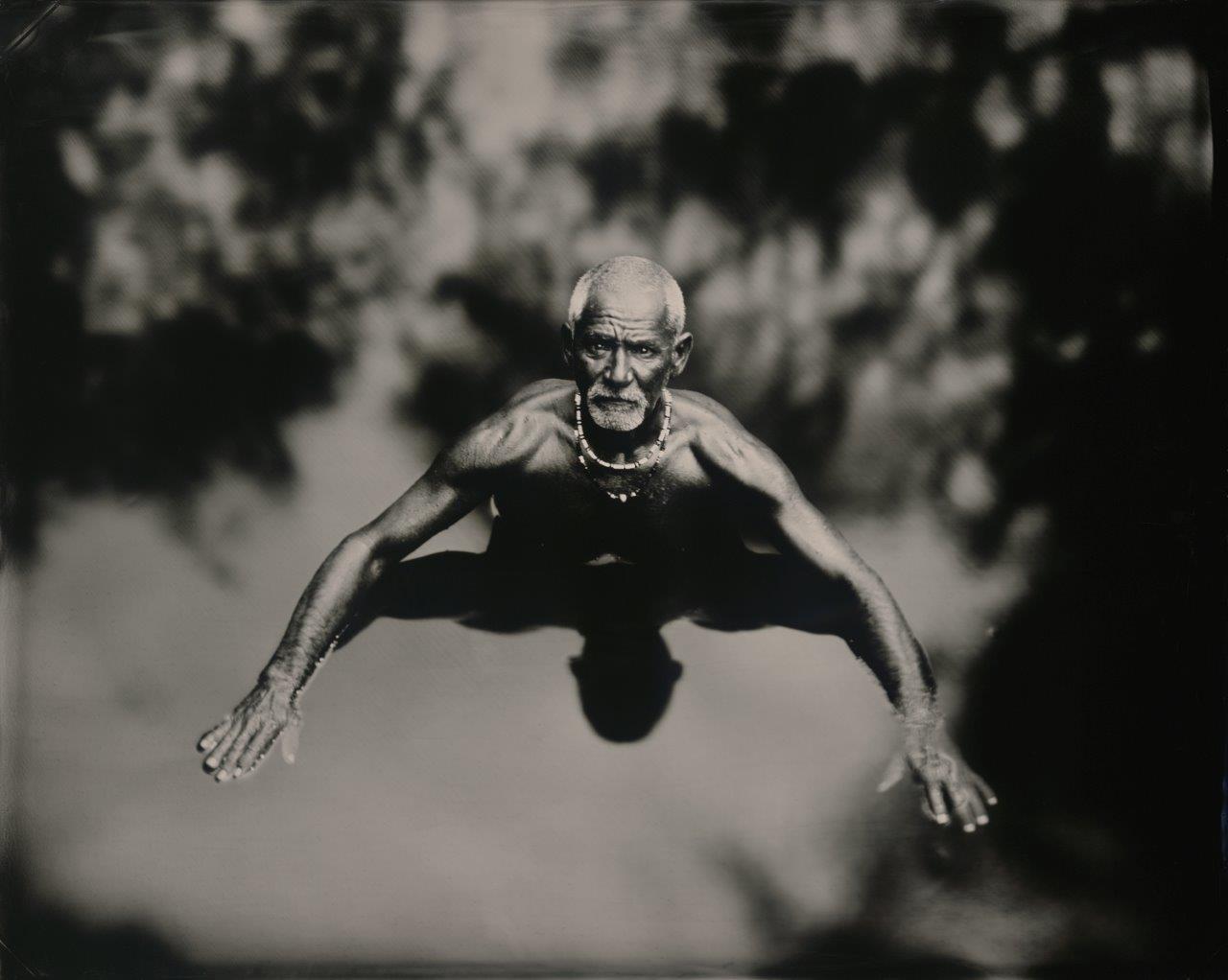

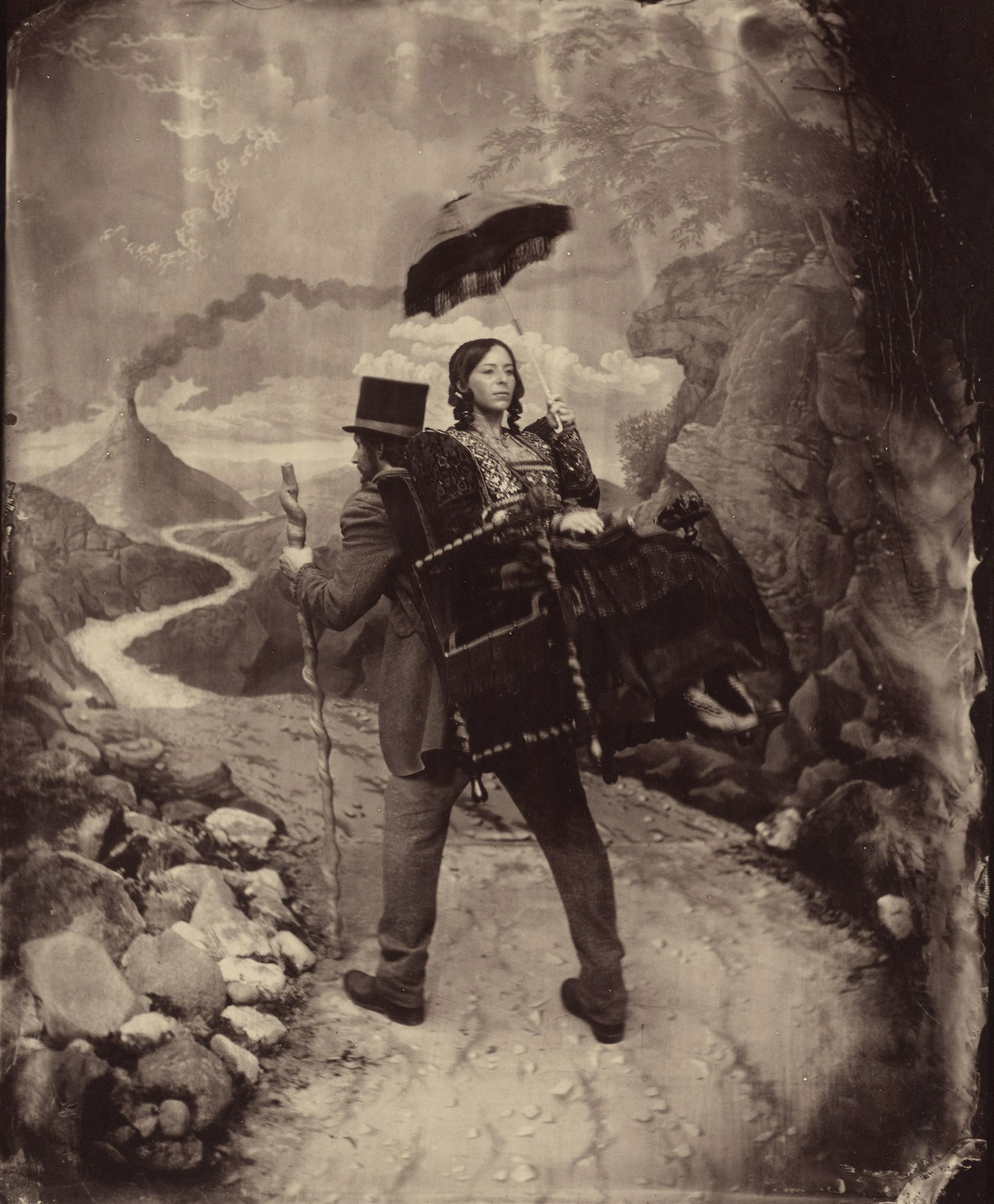

The photographer’s interest in this ancient method has driven him to curate a new exhibition, A New and Mysterious Art, featuring a selection of contemporary photographs using 19th century photographic processes. The works employ techniques ranging from daguerreotypes to photogenic drawings, and tintypes to camera obscuras.

Spagnoli says that the show came about as part of a larger push for a dialogue with contemporary artists, encouraging them to contemplate a range of processes when deciding how they will depict their ideas of the world. He believes, to an extent, that people are “under the misapprehension that these are obsolete and inaccessible processes.” The show, on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery through Oct. 29, presents work from artists Takashi Arai, Stephen Berkman, Dan Estabrook, Adam Fuss, Luther Gerlach, Vera Lutter, Sally Mann, Matthias Olmeta, France Scully Osterman & Mark Osterman, and Craig Tuffin.

Their works, he says, develop the “latent potential” of earlier processes that were never “fully recognized as an art” due to the rapid technical acceleration in photographic processes, which became fully industrialized by the 1880s. “This early stage, this primitive stage of photography was passed through much too quickly and in fact, in that period it wasn’t really recognized fully as an art. It was always considered just to be a documentation technique.”

Spagnoli himself pursued the antiquated daguerreotype technique in his own photography, piecing together the ancient process through reprints of 19th century materials, trying to “make heads or tails” of what they described in now dated vernacular. “There were a few people here and there who had a handle on how to produce a daguerreotype in at least some rudimentary fashion. So it took perhaps a dozen years to really, finally put together a way of making daguerreotypes,” Spagnoli tells TIME.

Spagnoli estimates there are only 15 to 20 people working seriously or routinely with the process, but predicts that daguerreotypes will endure as an art form into the future. “There will always be people who want to make still photographs for artistic purposes, just like there are still people who want to make oil paintings,” he says. “When you make the material from scratch and you produce all of the equipment, it gives you the ability to control the image that you don’t have with industrialized photography. And I think that there are going to be artists who find that very attractive.”

Chelsea Matiash is TIME’s Deputy Multimedia Editor. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @cmatiash.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com