History Today

This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at History Today.

Over the last 20 years there is no technology that has affected daily life as much as the Internet. From social media to supply chains, to shopping to online services, it has opened up countless new electronic opportunities and worked its way into the fabric of society. While we are right to be concerned about some of its effects, it is hard to see why a society would reject such an innovation as the Internet. Yet that is just what happened in 1980s Britain. Prestel, a nationwide information network invented by the Post Office, put homes and businesses online for the first time, offering information and services remarkably like those of the World Wide Web. For an exciting moment, it seemed that Thatcher’s Britain would become the world’s first online society, but Prestel never took off, becoming a mere footnote in the history of networking.

The story began in the early 1970s. At the time, the Post Office was responsible for Britain’s telephone network and an inventive Post Office research engineer, Sam Fedida, was attempting to produce a workable video telephone system, the Viewphone. The problem was that transferring enough data to carry a reasonable video signal over long distances was beyond the capacity of the 1970s telephone network. Tiring of Viewphone, Fedida started thinking about Viewdata, using the telephone network to supply homes with information from a computer databank. It was an idea very much ahead of its time. There were a few computer networks linking the big mainframe computers of universities and the military but nothing for the general public. Indeed, as hardly anyone had a home computer, Fedida thought to use the family television as the terminal to view information on, connected through the phone lines to a distant computer databank. (Prestel should not be confused with Teletext, also under development at the time. While superficially similar, Prestel was an interactive system relying on the phone network, while the passive Teletext was transmitted through the television signal and was far more limited in scope.)

To the management of the Post Office, it seemed a good way of increasing business by encouraging people to use the phone network more outside of office hours. Plans were laid to roll out the service, soon renamed Prestel, to the general public. Dozens of information providers were recruited to provide content for Prestel, for without content no one would want to use it. By the time the service was launched in triumph in 1979, it had 100,000 pages of information available. Sitting at their Prestel television, a user could call up a staggering range of information. Alongside news, weather and share prices, there were train timetables, information from major retailers and gardening advice. By the standards of the time, Prestel’s abilities verged on science fiction and it seemed that the Post Office had created a world leader. BBC TV’s Tomorrow’s World reckoned it would affect the lives of millions and it was even commemorated on a stamp. But there was one problem: people did not want to use it on anything like the scale expected. By the end of 1980 Prestel attracted just 6,000 users, mostly businesses rather than households. The Post Office’s hopes for a million users by 1985 seemed a long way off.

British Telecom (BT), which separated from the Post Office in 1981, made a renewed effort to entice users to Prestel. Overcoming the Post Office’s reluctance to compete with itself by offering electronic mail, Prestel introduced ‘Mailbox’ to allow users to send messages to each other. Online banking followed in 1983, courtesy of Homelink, run by the Bank of Scotland and Nottingham Building Society, offering many of the features expected today. Several theaters offered ticket booking facilities through Prestel and there were numerous large-scale experiments in online shopping. ‘The Armchair Grocer,’ for example, allowed people in the Midlands to order their weekly shop for delivery and there was even a ‘Beer at Home’ service. With Britain experiencing a home computer boom, services were launched for the millions of people who had bought their first computer, many of which could be connected to the network. Software downloads, chat rooms and online games were offered by a service named Micronet 800, which built an online community of several thousand enthusiasts long before the term ‘social media’ had been coined.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

By 1985 Prestel offered prototypes of many of the services found on the internet today. Yet despite all that was on offer, there were still no more than about 60,000 subscribers and the system was beginning to be seen as a flop. Much of the problem was cost. Televisions with Prestel built in were expensive: £650 for the cheapest model. Cheaper alternatives, such as modems for computers and adapters to allow non-Prestel televisions to use the service, were slow to appear on the market. A Prestel home subscription was £5 a quarter and, although free during off peak hours, access cost 5p a minute during the day. For the cost of a few minutes on Prestel you could buy a newspaper instead. There were other factors, too. The system could only display text and blocky graphics, no sound or video, leading some observers to claim it lacked excitement. Information technology was also new to most people. It was only in the 1980s that home computers started to introduce the general public to computing. Just what Prestel offered may have been hard for many people to appreciate.

Prestel limped on into the early 1990s, increasingly targeted at business customers. Its users peaked at just 90,000 and it was eventually sold off in 1994, dwindling to nothing. The Internet was just beginning its climb out of the academic networks that had nurtured it to become more widely available to the public. As for Prestel, the electronic world once populated by tens of thousands just vanished, having little impact on the Dot Com Boom looming on the horizon and leaving little behind but paper documents, screenshots and the memories of its users. Perhaps Prestel’s biggest legacy is in law. In 1984 hackers broke into the Duke of Edinburgh’s electronic mail on Prestel. It was just a bit of fun – they even sent messages teasing Prestel’s administrators about what they had done, but the resulting legal furor revealed that Britain did not actually have any law specifically against computer hacking. The case led to the Computer Misuse Act 1990, a foundational piece of British computer legislation, still with us today in updated form.

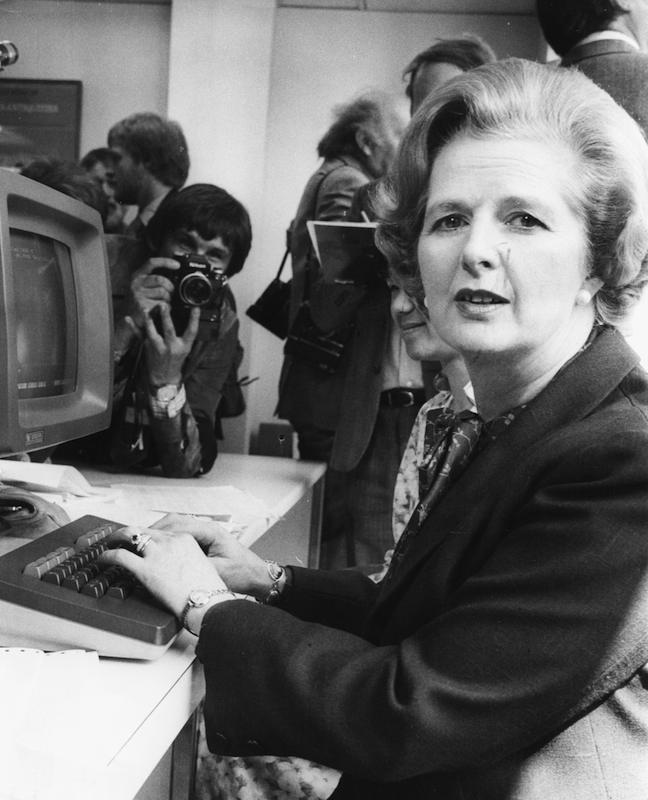

Prestel’s failure was not inevitable. In France, the similar Minitel system was a great success. Well funded by the French government, with schemes to hand out free Minitel terminals, it won millions of users and was only turned off in 2012. In Britain, government support was less forthcoming, with Margaret Thatcher’s liberalization of the telecoms industry, and the costs of going online remained too high. Yet, while it may have been a commercial failure, technically at least Prestel worked. The basic concept was demonstrably sound, giving thousands of people a glimpse of an online world that would later become commonplace. Perhaps it was not so much a failed technology, as one ahead of its time.

Tom Lean is the author of Electronic Dreams: How 1980s Britain Learned to Love the Computer (Bloomsbury, 2016).

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com