The lakeside restaurant at dusk seemed the perfect place to end what had been a busy day here at the luxurious Broadmoor Hotel.

Across the lake, the donors to Charles and David Koch’s political network were having dinner and then after-dinner drinks, with security guards keeping out interlopers and listening on their earpieces. Other guests at the grand, 3,000-acre retreat were largely indifferent to conservative and libertarian one-percenters on the western side of Cheyenne Lake as top Koch aides settled into a wooden table and ordered drinks.

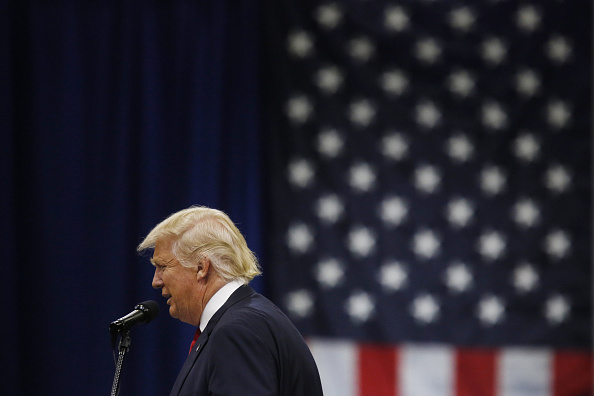

“I heard it’s Donald Trump over there,” one patron told his waitress. Koch executives overheard the comment and chuckled to themselves.

Of the roughly quarter-billion dollars these well-heeled donors were pumping into the 2016 ecosystem, not one dime is set to go to Republican nominee Trump. “We’re focused on the Senate,” Koch executive vice president James Davis said when a reporter brought up 2016, parroting what would be his default line no matter the question about the White House race between Trump, a Koch enemy, and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. “We’re focused on the Senate,” Davis said again with a smile. Then, turning to his pint glass, he shook his head. “I’ll be saying that in my sleep tonight,” he said with a disbelieving chuckle.

That refrain about the Senate pervaded the three-day retreat here in the Rocky Mountains. From Charles Koch himself to rank-and-file donors, everyone was unified in their message that the Senate this fall matters more as a safeguard against either outcome than the White House, and that Trump was not going to benefit from this well-oiled network’s efforts.

“We’re dealing with limited resources,” said Frayda Levin, a Mountain Lakes, N.J., businesswoman and longtime Koch supporter. “I know what is written about us. But we’re not bottomless wallets. Where can we do the most good?”

In conversations with more than two dozen Koch insiders this weekend, it is clear that there is no affinity for Trump, the reality star who rocketed past Koch-aligned candidates to capture the GOP’s nomination. Charles Koch, the $45 billion man himself, made little secret about his feelings: “At this point, I can’t support either candidate.” His pals — some of whom have known him for decades and have supported his network of conservative and libertarian think tanks, advocacy groups and political machines — were largely in agreement. For them, their main electoral focus needs to be on Senate races in six states to defend the GOP majority: Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Wisconsin, Nevada and Florida.

“A lot of groups are working on the presidential. We don’t have to be one,” said Ed Meese, who served in President Ronald Reagan’s Cabinet and is a Trump supporter who made the case to his friends that they, too, should be. “He’s the Republican nominee.” Meese found few converts, and Trump did himself any favors by picking a fight on Twitter with the Koch network as its members were arriving in Colorado Springs.

Trump, who was in Colorado Springs for other purposes, claimed he turned down an invitation to meet with Charles and David Koch. He then insulted those who were here, including House Speaker Paul Ryan and the governors of Kentucky and Arizona, as puppets. Top Koch lieutenants very delicately tried to dispel Trump’s assertion without explicitly calling him a liar. “You’ll have to talk with him about what his facts are and what he’s relying on,” said Mark Holden, the Kochs’ longtime attorney and chairman of their advocacy umbrella, formally known as Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce.

But it was clear to everyone that the presidential race offers little reason for smiles to these ultra-influential donors. There was a begrudging acceptance that Trump was not coming from nowhere. (Nor was democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, who mounted a spirited campaign against Clinton and won 23 states.)

“The American people are fed up with the Establishment,” said Tim Busch, a businessman from Orange County, Calif. “This is like 1968 all over again.” But, he adds with an eye roll, Trump’s promises of a trade war and mass deportations would only make it worse. If only someone like Paul Ryan had joined the race, he pines. Even so, Busch is a solid Trump voter in deep-blue California based on the issue of abortion. “He’s my only choice. He says he’s pro-life. We’ll see, won’t we?”

It was similar for Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin, who has not endorsed Trump but says the country cannot afford Clinton. “There is discord in the American political spectrum. There is a level of dissonance in both parties. It is what we have seen at a national level,” he said Monday in a courtyard of the Broadmoor. “It’s not like anything we’ve seen in our lifetimes.”

“We have a different kind of nominee now. It’s unique,” Ryan told chuckling donors shortly after at a luncheon.

To help these donors understand how the politics had changed, and how rapidly, organizers tapped a professor at the conservative Kings College, Brian Brenberg, to walk them through things. (The Koch network also funds such educators and programs on campuses, and given the political environment, they are expected to boost this as a share of the $750 million they plan on spending.)

“Unless we address these underlying issues, these underlying threats, candidates, elections, they’re only going to become more extreme and more divisive,” Brenberg said in a well-received speech that resembled a TED Talk more than a donor pitch. “If history has taught us anything, it is this: when a citizenry feels neglected and ignored, they will line up behind leaders who give voice to their concerns and promise relief of their problems — even when the eventual outcome is likely to be far, far worse.”

Brenberg, however, had a measure of honesty for his audience. “For a lot of us in this room, like a guy in Manhattan, it’s easy to lose touch with the average American voter,” he said, noting that most Americans were saving little and struggling just to get by. It was a stark reminder to this crowd, who each ponied up at least $100,000 each year to get an invite to the retreat. “Is it any wonder that voters are gravitating to non-Establishment candidates? They’re just looking for someone who will acknowledge their reality,” the dual-Harvard-degreed scholar asked.

And there is the dilemma for this Koch-led network. Americans’ economic anxiety is high, confidence is low, and the nation’s electorate is lashing out. The donors nodded along as presenters made the case that the Senate is a safety valve against whoever wins the White House, perhaps pushed to act in ways that reflect the rage.

“I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this since George Wallace,” said Art Pope, a mega-donor from North Carolina. “My concern is Donald Trump will depress the Republican vote and hurt down-ballot candidates.” With an estimated $250 million ready to pump into those lower races — including $42 million in ads for Senate hopefuls — they will have some padding. Now they just need to block out the presidential race that they find unimaginable.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott / Colorado Springs, Colo. at philip.elliott@time.com