With the U.S. in the midst of a massive heat wave during one of the warmest years on record, it is, in a word, hot. As temperatures rise—and look to keep rising over the coming years—the dangers of remaining outside for too long are very real. And so is the relief that comes with entering an air-conditioned building.

For that, today’s hot and sweaty masses have the engineer Willis Carrier to thank. Though people have attempted to outsmart the weather for centuries, the mechanical air conditioner did not arrive in the U.S. until Carrier invented it in 1902.

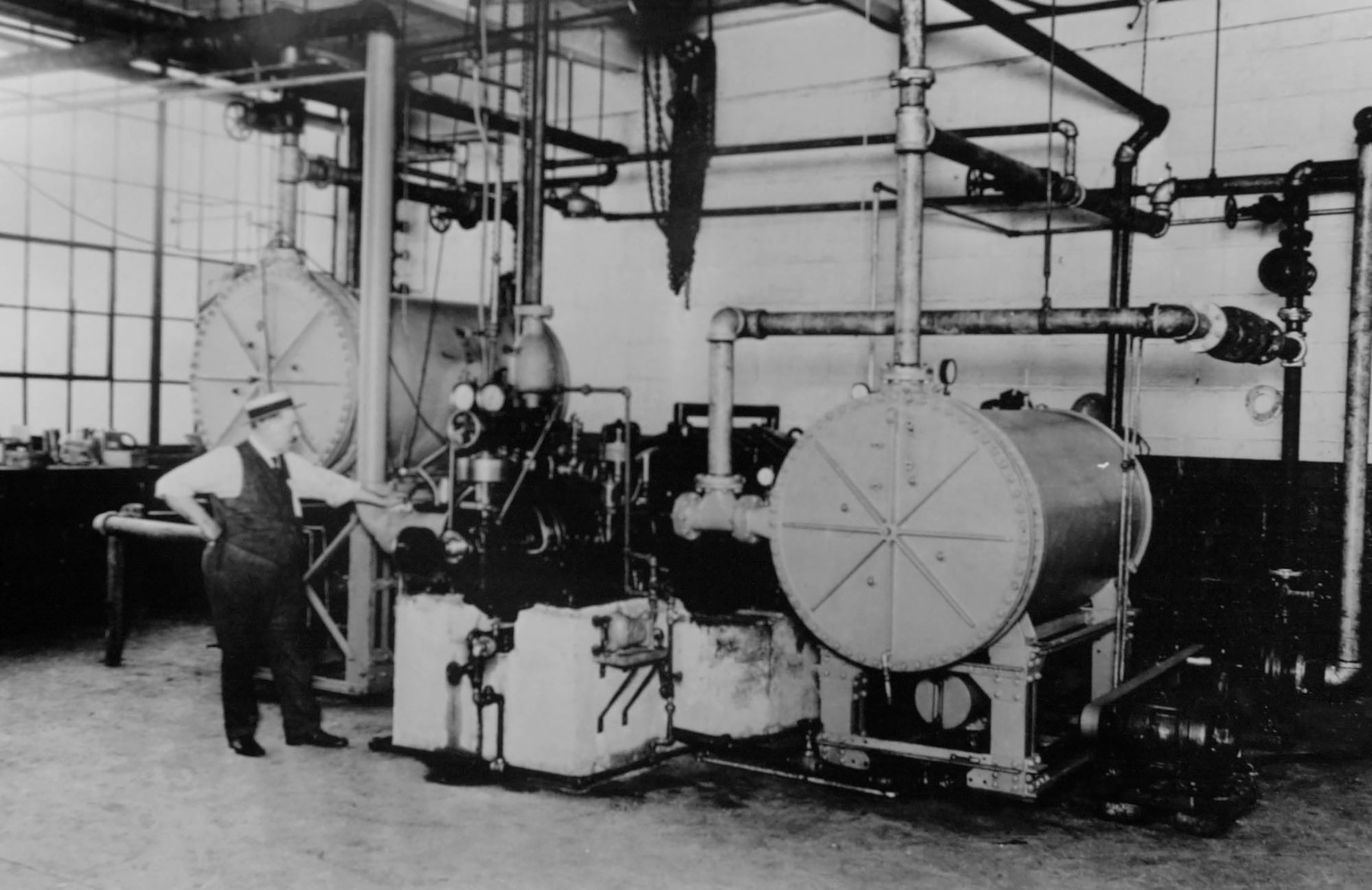

Carrier, who saw himself as the Thomas Edison of air conditioners, changed the world with his invention—but its original aims were much smaller than that. The air conditioner, built to both cool a room and reduce humidity, was originally created to keep moist air in a printing plant from wrinkling magazine pages.

Carrier had been born in 1876 to an old New England family—including an ancestor who was hanged as a witch in Salem—and attended Cornell University, after which he took a job with a heating outfit. Research he produced for the company saved them $40,000 a year, and Carrier was put in charge of a new department of experimental engineering, where he designed his first air-conditioner for the printing plant. While there, he met Irvine Lyle, a salesman and his eventual partner in Carrier Corp., a company that succeeded in marketing the air conditioner to Americans in the 1950s. (Today, it is a brand of United Technologies.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Carrier continued to refine his cooling systems over the 20th century. As TIME explained in a 2010 brief history of air conditioning, it took years for the technology to become widespread:

Advances in technology eventually yielded the more convenient window air conditioner in the late 1930s, though it remained out of reach for most. The general public—those not privy to the few luxurious hotels and cars that used cooling systems early on—often first encountered air-conditioning in movie theaters, which started to widely use the technology in the 1930s. Before the window unit’s heyday, Carrier produced a system for theaters that cost between $10,000 and $50,000. It was one of the few things proprietors sprung for during the Great Depression, and theaters were one of the rare places where the hoi polloi could enjoy chilly, artificial air.

Eventually, air conditioners lost their aura of luxury. Today, almost 90% of U.S. homes have air conditioning, and global demand for cooling systems is staggering, bringing relief to more than 3 billion people who live in the tropics and subtropics, according to a 2015 study from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

And Carrier’s influence doesn’t stop there. A 1998 essay from TIME entitled King of Cool delves into how deep the air conditioner’s reach goes:

As anyone who has ever suffered through a brutal summer can tell you, if it weren’t for Carrier’s having made human beings more comfortable, the rates of drunkenness, divorce, brutality and murder would be Lord knows how much higher. Productivity rates would plunge 40% over the world; the deep-sea fishing industry would be deep-sixed; Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel would deteriorate; rare books and manuscripts would fall apart; deep mining for gold, silver and other metals would be impossible; the world’s largest telescope wouldn’t work; many of our children wouldn’t be able to learn; and in Silicon Valley, the computer industry would crash.

While for most, air conditioners promise cold, blissful air, not everyone is on board for Carrier’s invention. Environmentalists concerned about global warming have for years called for cutting back on the use of air conditioners, although they recognize the invention’s public health benefits. However, as record-breaking temperatures are expected for the coming decades, air conditioning likely isn’t going anywhere.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com