The gloves are off in the 2016 Presidential race, yet this week the City of Brotherly Love — Philadelphia — will host the Democratic National Convention. On the surface, it seems unfitting. There’s been little love so far in the presidential campaign. Trump blames Clinton for our plight. She blames him for inciting prejudice. If there’s one point of agreement, it’s that America is in crisis. If there’s one common goal, it’s sweeping change. Do we need a savior or do we the people need to save ourselves first?

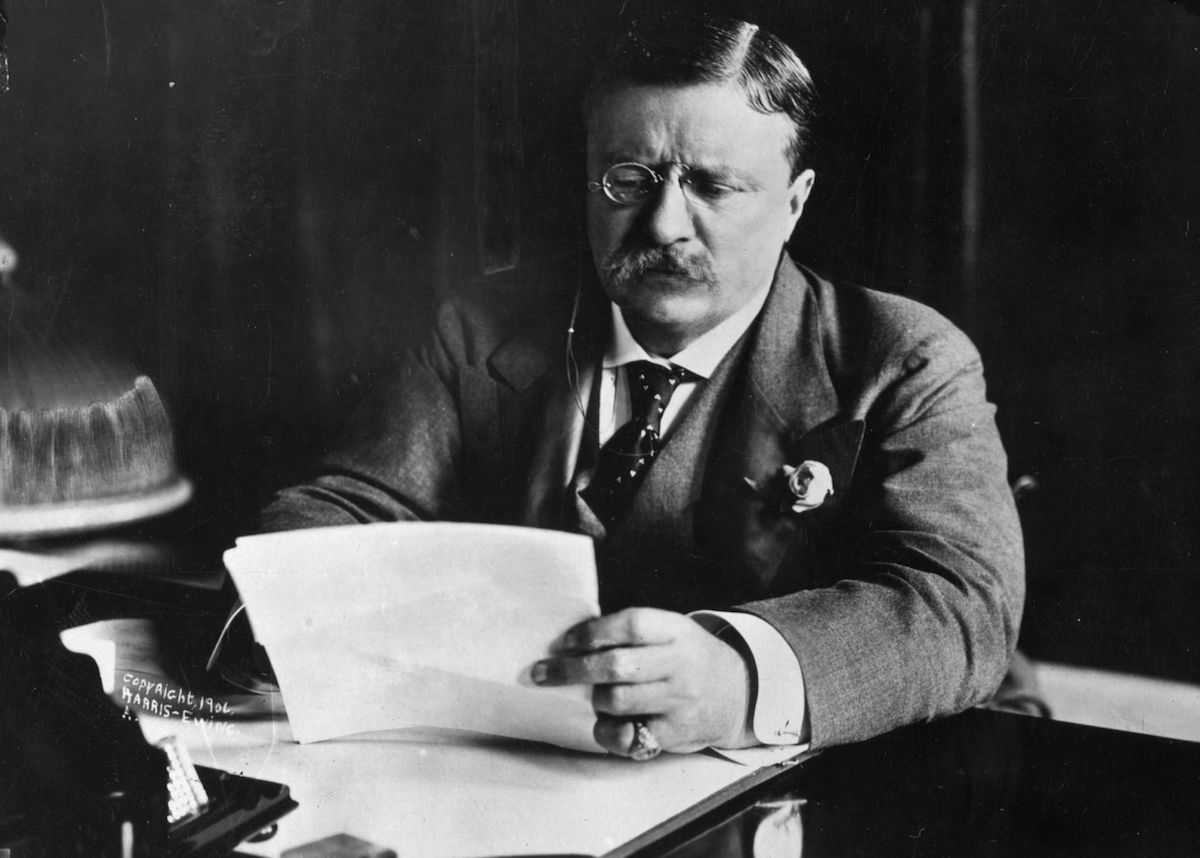

Theodore Roosevelt’s name has been invoked by both sides of the aisle as a model of powerful leadership. Some people lament that there is no such figure on the national stage nowadays; some suggest that Trump is actually the modern version. That seems unlikely: Roosevelt likewise disrupted the Republican Party, but he did so as a two-term former President with additional years of government and military service.

So the disruption we’re seeing now is something different. That doesn’t mean there’s no modern T.R. out there, or that his story has nothing to say about today’s political climate. In fact, in some ways his story parallels America’s—and shows us how we can use the past to understand the present.

In 1884, Theodore Roosevelt was 26, an energetic New York Assemblyman married two years to his college sweetheart, Alice Lee. He was something of a dandy, known for his kid gloves and high-pitched voice. But he was a hard worker, fighting corruption and seeking to improve the working conditions of the poor. Even the day before their first child was due, he was in Albany, shepherding a reform bill through the Assembly. A telegram found him in the legislative chamber: Alice had given birth to a girl. An ecstatic Theodore accepted congratulations and made plans to return home.

A second telegram turned those plans to a panicked rush. Struggling through dense fog, Theodore made it home near midnight. His brother Elliott met him at the door, ashen. “There is a curse on this house.” Alice was dying, and Theodore’s mother too. He went from one bedside to another as they succumbed, eleven hours apart. Theodore wrote a black X in his diary, then a single sentence: “The light has gone out of my life.” It was Valentine’s Day.

The old life could not go on. Theodore stayed long enough to see his daughter christened Alice, then deposited her in the care of his sister. Back in Albany, he worked frantically for the rest of the year but refused to stand for another term. Instead, he went West, to the Badlands of North Dakota. There he rounded up cattle, hunted grizzly bears and slowly began to heal. The endless plains were a place to lose himself and escape his grief. “Black care,” he wrote, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.” He stopped stampedes; he knocked out a drunken cowboy who mocked his spectacles. When thieves stole his riverboat, he chased them miles up the Little Missouri, captured them and brought them back for trial.

When he returned East, he was a different man: stronger and unafraid.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

America has gone through the same sort of transformation and reforging of identity that Theodore Roosevelt experienced in the Dakotas, the same process of reinvention. It started in Philadelphia, in Independence Hall: the place where our Founders drafted both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

By 1776, when the Declaration was written, the thirteen colonies had been at war with Great Britain for a year. As it was read out to the public for the first time in the yard of Independence Hall, a large British army stood poised to seize New York. The Declaration created a new American identity. It transformed thirteen rebellious colonies into free and independent, but united, states.

Acting together, the new states prevailed against the British. But independence came easier than durable unity. Under the Articles of Confederation, the nation organized itself into a loose league that respected the sovereignty of the states. This confederation soon proved inadequate. Virginia and Maryland fought a brief war over oysters. As the delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered at Independence Hall in the summer of 1787, Connecticut and New Jersey were making plans for a concerted attack on New York. The American experiment teetered on the brink of disaster.

But again, America emerged from the crisis with a new and stronger identity. The Constitution created a single country with a government powerful enough to protect the national interest.

Crisis has followed crisis, but each time, the nation has been able to find in danger the seeds of opportunity; we have emerged from each struggle both stronger and better. The Civil War challenged the more perfect union promised by the Constitution, but America survived the challenge—and, after it was over, amended the Constitution to ban slavery, reaffirm federal authority and protect individual rights of liberty and equality against oppression by the states. The nation that emerged from the Civil War was both more united and more just.

World War II saw the shadow of fascism over the world. American ideals were under threat from external attack, and at home they were compromised by fear. Succumbing to prejudice and baseless panic, the federal government drove 120,000 people of Japanese descent—most of them birthright citizens under the 14th Amendment—from their homes on the West Coast and detained them in camps in the interior of the country.

Even from this episode, though, the country emerged better. The Supreme Court realized it had made a mistake. It became more sensitive to the ills of racial discrimination and more skeptical of government claims of military necessity.

In each of these cases, it has been the process of struggle, suffering and reinvention that has brought forward the real essence of America.

We shouldn’t look to the past because the Founders had all the answers; we should look back to be inspired by the challenges we’ve overcome, and to learn from the mistakes we’ve made. And as the Democrats gather in Philadelphia, in the shadow of Independence Hall, it’s a good time for all of us to think about who we are and who we want to be.

Kermit Roosevelt is the great-great-grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt and a professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. His latest novel, Allegiance, is about the Supreme Court in WWII.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com