In the history of the Republican Party, some states get more credit than others. The Party’s founding is traced to an 1854 gathering in Wisconsin, with a larger follow-up held later that year in Michigan and the first national convention held two years later in Pennsylvania.

Though its role is less well known, Ohio—where the party will meet this week for its national convention—deserves credit, too.

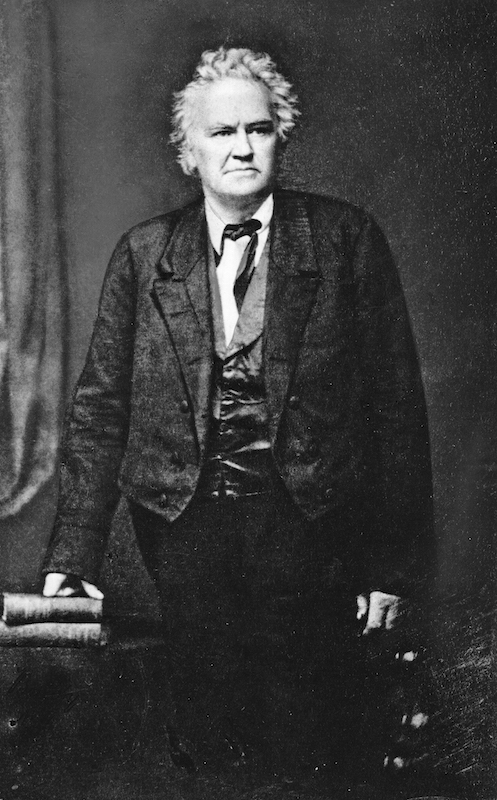

Case in point: Joshua Reed Giddings, whom the experts at the Ohio History Connection, a state historical association, highlight as an important part of the state’s long association with the GOP.

Before the establishment of the Republican Party, Giddings—a lawyer whose office in Ashtabula County is on the National Register of Historic Places—was a Whig politician and abolitionist who served in the state House of Representatives and then in Congress, starting in 1838. He resigned his post in 1842, after being disciplined by the House for arguing that people held in slavery by Americans were free when they left U.S. territory (an issue that arose after slaves on the ship Creole mutinied and sailed to the Bahamas). Promptly reelected, he continued to serve for many years, eventually representing current RNC locale Cleveland after a redistricting. When the Republican Party was founded amid the dissolution of the Whig Party and uproar over slavery, Giddings became one of its earliest members.

“What you pick up in going through [Giddings’] papers is the back and forth with other Ohioans about the importance of founding a new party,” says Tom Rieder, Ohio History Connection archivist. “He and Salmon P. Chase, around the time of the meetings in Michigan and Wisconsin, were doing similar work in Ohio.”

Giddings was responsible, Rieder says, for making sure that the first Republican Party platforms emphasized the idea that all men are created equal.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

And, says Rieder, Ohio was ideally located for that work.

Ohio had been settled by a combination of evangelicals from the Northeast and a heavy dose of antislavery Quakers from North Carolina, but it also directly abutted a slave state. Runaway slaves fleeing Kentucky would end up in Ohio first; Giddings’ home is said to have been a stop on the Underground Railroad. The population (though not immune to some of the nativist and anti-Catholic sentiment sweeping the nation) was primed for an abolitionist party to take hold. Voters in Ohio were also, as Thomas W. Kremm has argued in the Cincinnati Historical Society Bulletin, generally anti-establishment—a tradition that today’s voters might appreciate—and ready for a new political system. The Republican Party, with its anti-slavery background and fresh perspective, stepped into the void.

That’s a past that resonates today on both sides of the aisle. Ohio State Representative John Patterson, a Democrat, has been active in the restoration and preservation of Giddings’ home and office, and he says that the lesson of Ohio’s Republican past transcends party lines.

“Especially now, in light of the social climate in our nation in general, the Giddings message still speaks powerfully to us,” says Patterson. “He was one who understood, and it was deep-seated in his very nature, about equality.”

In fact, Patterson says, the equality that Giddings fought for is perhaps even more complicated today than it was in Giddings’ lifetime: the evil of slavery was easy to identify, whereas today’s inequalities are likely to be subtler and to span across many different groups of people.

That’s why Patterson cites his favorite quote from Joshua Reed Giddings.

“My heart’s desire and prayer to God, shall be that every human soul may enjoy that liberty which is necessary to protect and cherish life, attain knowledge and prepare for heaven,” Giddings said. “And when I have passed away let my epitaph announce that I hated oppression and wrong,—that I loved liberty and justice.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com