As Pokémon Go fever sweeps the nation and the world, the inevitable concern backlash has begun: reports are in that players have been the target of armed robberies, and that at least one player has been led to an experience (finding a dead body, for example) that was far from the fun promised by the augmented-reality game.

But this isn’t the first time that Pokémon has stirred worries over players’ health and well-being.

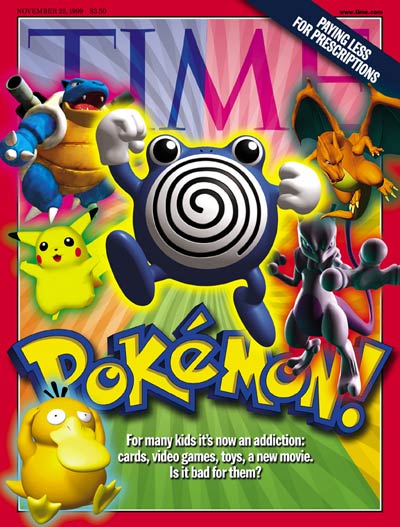

In 1999, when the first Pokémon movie was released in the U.S., TIME featured the fad in a cover story. And, though the magazine took pains to explain the craze to curious readers unfamiliar with the charms of Charmander, the main note struck by the story was one of concern. The main fear sparked by Pokémon back then wasn’t that people would get hurt—even though, according to the story, a 9-year-old in New York had stabbed a schoolmate in a fight over trading cards. The real problem was that collecting Pokémon brought out a streak of avarice that was unappealing in children:

A principal explained why her school, like many others, was banning Pokemon cards: “Children who don’t have Pokemon cards feel left out. When children bring the Pokemon cards into the lunchroom, they often spend time looking at the cards instead of eating lunch.” A group of parents in New Jersey has sued the trading-card manufacturer for intentionally making some cards scarce to force children into buying more and more packs of Pokemon cards. “Racketeering!” the parents cry.

It’s not really the violence that scares parents—they’ve lived with and tolerated intimations of horror for generations. In Grimm’s fairy tales, what does the wolf do to Red Riding Hood’s granny or the witch plan to do to Hansel? When kids collect dinosaurs, parents, blinded by science, simply shrug when their children yell in the museum, “Look, mom, that allosaurus is eating the brachiosaur’s baby!” After that, what can be objectionable about the too-cute-to-live Pokemon named Jigglypuff, a ball of fluff whose greatest power—not to be scoffed at—is a stupefying lullaby?

But there is a problem: the key principle of the Pokeocracy is acquisitiveness. The more Pokemon you have, the greater power you possess (the slogan is GOTTA CATCH ‘EM ALL). And never underestimate a child’s ability to master the Pokearcana required to accumulate such power: the ease with which they slip into cunning and thuggery can stun a mergers-and-acquisitions lawyer. Grownups aren’t ready for their little innocents to be so precociously cutthroat. Is Pokemon payback for our get-rich-quick era–with our offspring led away like lemmings by Pied Poke-Pipers of greed? Or is there something inherent in childhood that Pokemania simply reflects?

One psychologist told TIME that Pokémon was relatively harmless, as long as children didn’t start to confuse the world of the game with the real world in which they lived the rest of their lives. Considering that criterion, it’s no wonder Pokémon Go has brought Pokémon fears back to life.

Read the rest of the story here, in the TIME Vault: Beware of the Poké-mania

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com