On June 30th, 1908, an asteroid entered the Earth’s atmosphere above Tunguska, Siberia and exploded with the energy of about 185 Hiroshima-level atomic bombs. In memory of that catastrophic event, every year on June 30th is Asteroid Day, a “global awareness campaign where people from around the world come together to learn about asteroids and what we can do to protect our planet, families, communities, and future generations from future asteroid impacts.”

Rocks from space are constantly bombarding the Earth. While most burn up completely in the atmosphere, some larger ones are able to reach the Earth’s surface. When they do, they leave behind an impact crater. Most impact craters are eventually erased due to erosion, vegetation growth, and the movement of the Earth’s tectonic plates. (On the pesky matter of terminology: a rock in space is an asteroid; a rock in space that enters our atmosphere is a meteor; a rock in space that enters our atmosphere and reaches the ground is a meteorite.)

In the rare case that an impact crater is preserved, water can fill the depression, creating a lake. When the lake is connected to the region’s water system, it is almost indistinguishable from any other lake, except to geologists who study the composition of the rocks, searching for ‘impactite‘, a type of melted rock that forms in a meteorite strike. In other cases, when the water that has collected is unconnected, impact crater lakes can provide a valuable geologic and fossil record by preserving ancient sediment.

Clearwater Lakes (Lac à l’Eau Claire), Quebec, Canada

About 290 million years ago, two large meteorites crashed into Earth and formed the two impact craters the make up this lake system in Quebec’s largest national park. Originally close to the equator, these craters were slowly pushed into northern Canada by millions of years of plate tectonics.

Pingualuit Impact Crater, Quebec, Canada

The name of this remote, 1.4 million year old crater comes from the Inuktiut word for skin blemishes that form in cold weather. The 876 foot deep lake has no connection to any other body of water, making it a valuable research source for scientists studying sedimentary records.

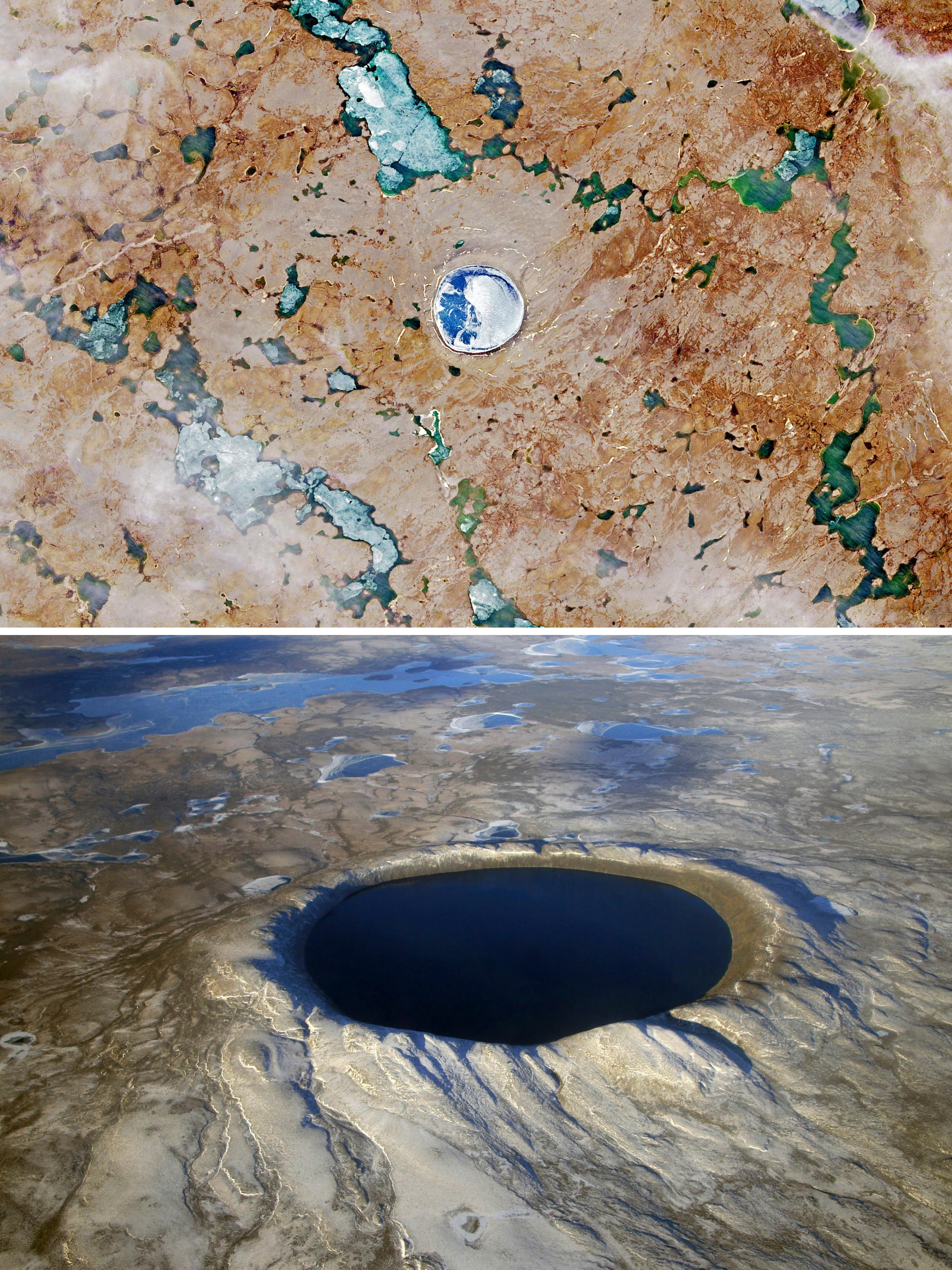

Tswaing Meteorite Crater Reserve, Soshanguve, South Africa

Meaning, “place of salt” in Setswane, this salt-rich lake was first visited by homo sapiens as far back as 100,000 years ago. The 650 foot deep crater was left by a meteorite over 220,000 years ago. More recently, in the 1900’s, a factory producing soda ash and salt was based there.

Lake Acraman, Gawler Ranges, Australia

590 million years ago a large asteroid smashed into what is now southern Australia, creating a 55-mile wide crater and disturbing rocks as far away as 95 miles. Today, the center of the crater forms a shallow salt lake. Due to a dramatic change in the fossil record around the time of impact, some studies suggest that this asteroid could have had a dramatic effect on life on Earth at the time.

Kaali Meteorite Crater Field, Saaremaa Island, Estonia

About 7,500 years ago, a meteor broke apart above the Earth’s surface, forming several small craters when it hit. The site might have been considered sacred by its Late Bronze Age inhabitants. Archaeologists have uncovered a stone wall from the time period as well as a large number of animal bones, hinting at animal sacrifice.

Lonar Meteorite Crater, Deccan Plateau, India

For many years, Lonar crater was thought to be volcanic in origin, due to its location in a basalt field made from volcanic rock from 65 million years ago. However, a Science article in 1973 pointed to the presence of maskelynite, a glass that is only formed from high velocity impact, as proof that the crater was extraterrestrial in origin. The impact occurred between 35,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Lake Dellen, Hälsingland, Sweden

The Dellen crater forms a round lake system consisting of two lakes, Northern Dellen and Southern Dellen. The 89 million year old impact crater contains a type of rock formed by asteroid strikes called tagamite, or dellenite.

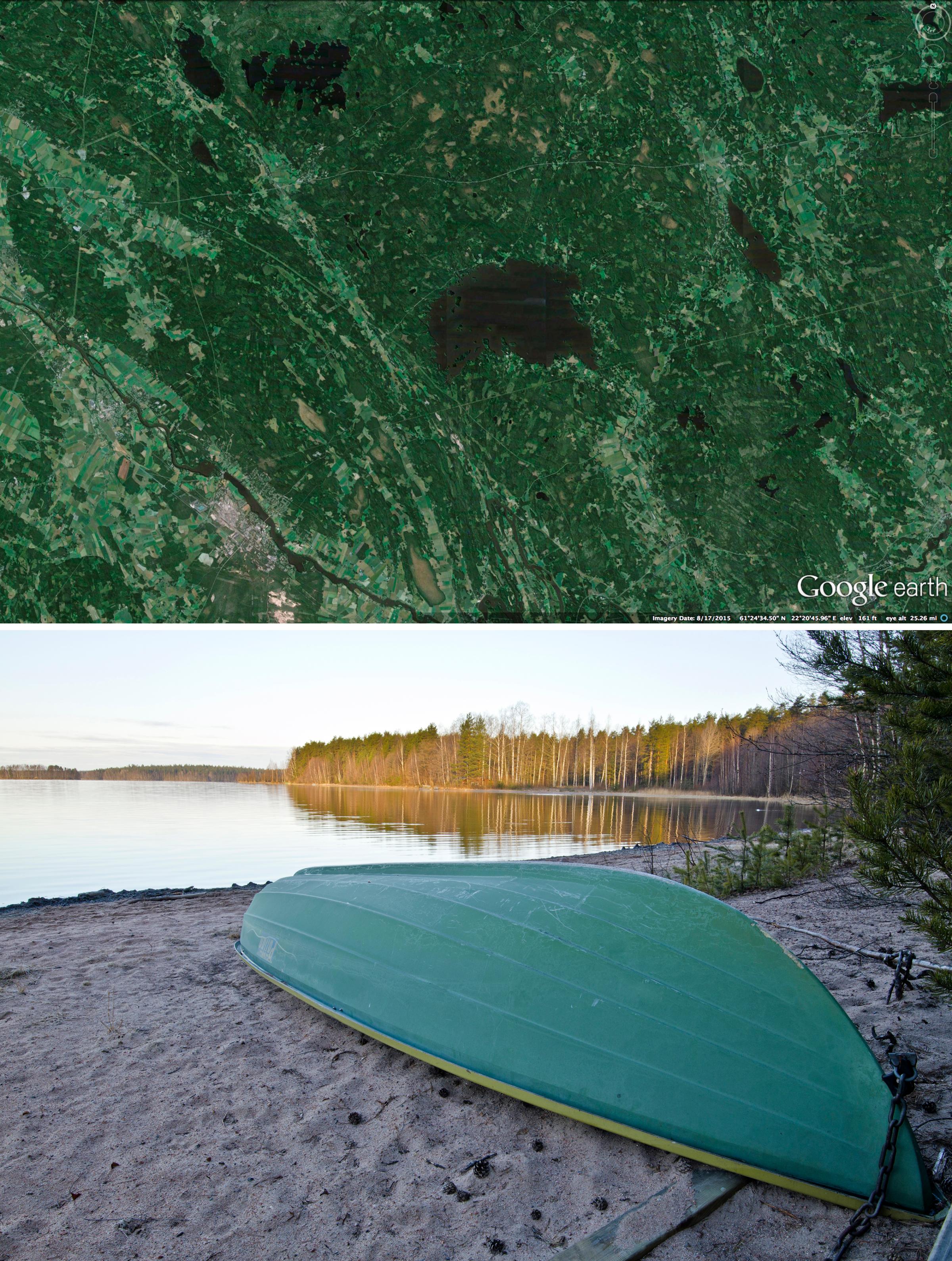

Lake Sääksjärvi, Satakunta, Finland

This 500-600 million year old crater is 3 miles in diameter. While it is now completely buried under the overlying lake, geologists were able to determine its presence by studying the impactite rocks in the area.

Lake Jänisjärvi, Karelia, Russia

The crater that forms this lake, near the Finnish border, is 700 million years old, pre-dating mammals, dinosaurs, and fish. Impactite, a type of rock that has been changed by a meteor impact, blankets the area, especially the islands in the center of the lake.

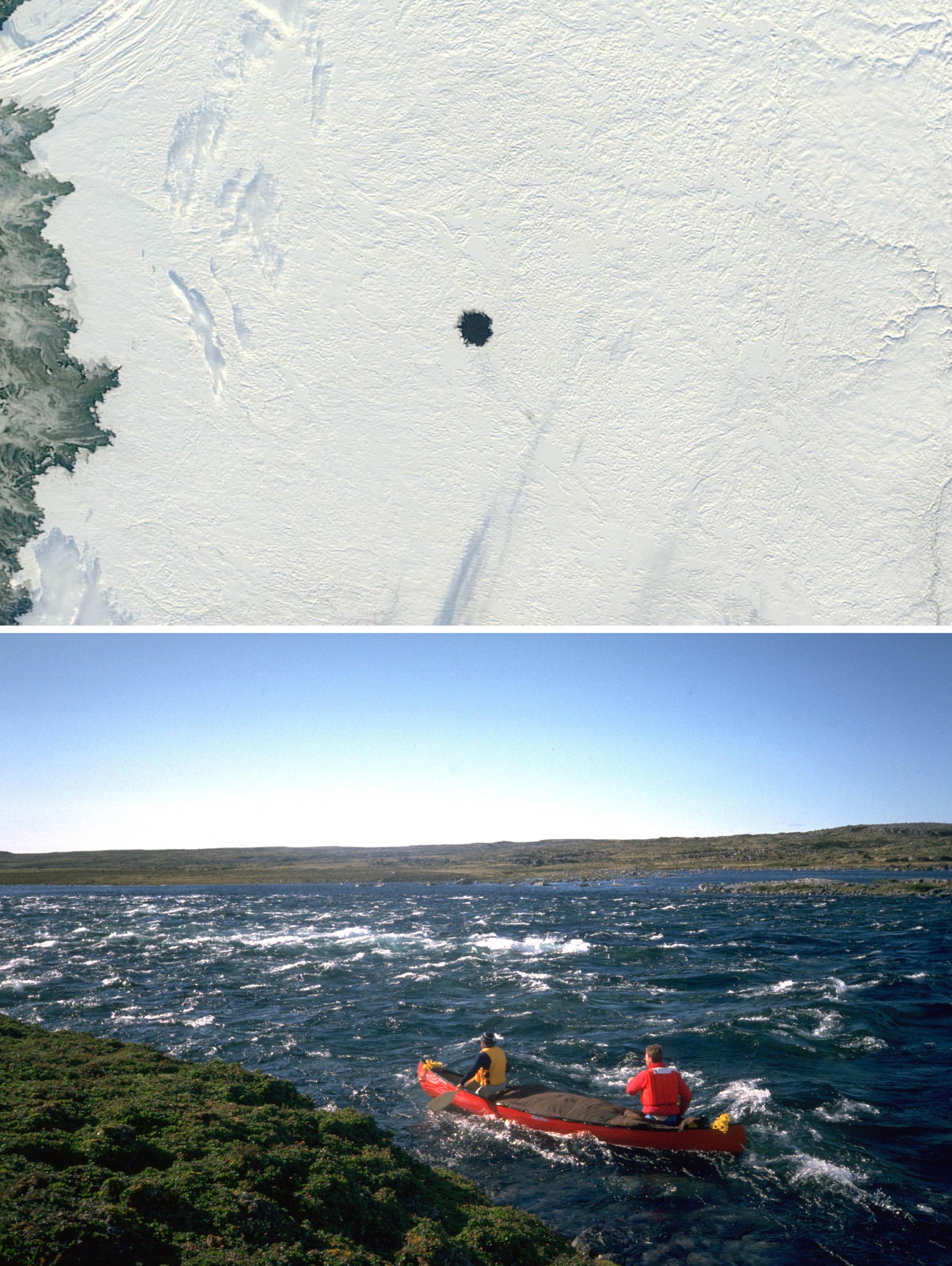

Lac Couture, Quebec, Canada

Because Lac Couture, formed by meteorite impact 425 million years ago, is so much deeper than the other non-extreterrestrial lakes in the area, it is often the last to freeze over in the winter, even in the intense cold of the Canadian tundra. The Couture crater is 5 miles wide and 490 feet deep.

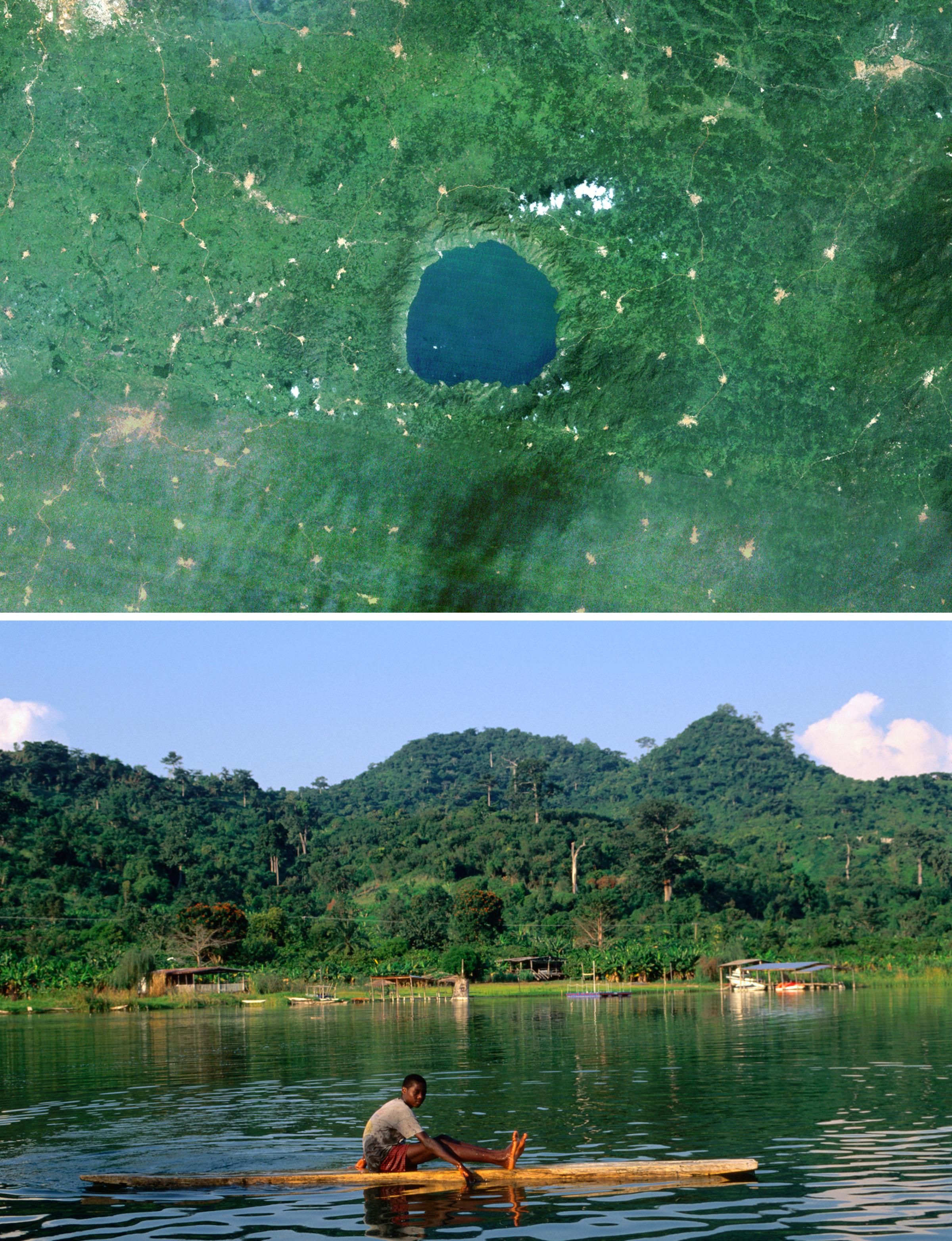

Lake Bosumtwi, Ashanti, Ghana

The almost circular Bosuntwi crater is about 1 million years old. Because this lake does not connect to other water sources in the area and its sediment is well preserved, it has become an important resource for scientists studying climate change.

Lake Kara-Kul, Pamir Mountain Range, Tajikistan

Kara-Kul, which means “black lake” in Tajik, was formed from a meteorite impact around 25 million years ago. The 16 mile in diameter lake, which is fed by glacial streams but does not drain, is salty and bitter.

Lake Manicouagan, Quebec, Canada

This ring-shaped lake in northern Quebec is one of the largest impact craters still preserved on Earth. Some scientists believe that the impact from 5 mile in diameter rock may have caused a mass extinction event 212 million years ago. Today, the lake is a reservoir and an important region for Atlantic salmon.

Lake Siljan, Dalarna, Sweden

Lake Siljan forms the south-eastern part of the Siljan Ring, Europe’s largest impact crater at 32 miles in diameter. It is about 377 million years old.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com