In May 1910 pioneering pilot Glenn H. Curtiss brought all of Manhattan to a standstill with a record-breaking feat of aviation.

At the time, Curtiss was fighting a legal battle to break the Wright brothers’ monopoly over all powered human flight, but it was bleeding him dry. In order to pay his lawyers, Curtiss had to do the impossible. He had to win an impossible prize.

Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World had put up $10,000 ($250,000 today) for anyone who could complete the 150-mile journey from Albany to New York in an aeroplane. If Curtiss could win Pulitzer’s prize, he could sustain his battle to open the skies to innovation.

The stakes of Curtiss’s flight from Albany were lofty. Ever since Wilbur and Orville Wright became the first humans to master powered flight back in 1903, they had zealously pursued legal action against anyone who tried to take to the sky in an airplane without paying them. Since the Wright brothers were the pioneers of a new technology, they claimed that U.S. patent law gave them a sweeping monopoly over every possible design for airplanes, even ones they had not invented. The brothers did not care that Curtiss had actually built a better aircraft, or that his innovation for controlled flight was superior to their outmoded technology; because they were first, Curtiss had to cough up royalties for the privilege of flying.

Curtiss was hell-bent on fighting that absurd claim. What was the use of improving technology if someone else—in this case, the Wright brothers—got to profit from his own hard-won inventions? Today this same fight is being waged across the computer and software industries. In 1910 the battleground of intellectual property law was the sky.

Curtiss chose the morning of Sunday, May 29, to try to snatch Pulitzer’s prize money and continue the legal war against the Wright brothers.

The weather that morning was perfect for flying. The winds were mild. The sky was almost completely clear of clouds. As he prepared for takeoff, Curtiss donned a cork-lined life vest and put his legs into a pair of rubber fishing pants. The curious apparel was not so much to keep him alive, in the event of an emergency landing on the Hudson, as to keep him warm once he was aloft in the rushing air.

Dressed for the flight, the mustachioed aviator took up position on the lower wing of his aircraft. When Curtiss accelerated the motor, his aircraft hurtled down a stretch of open land east of Albany. Ever so gracefully, the pilot and his flying machine climbed into the air.

The race was on.

Chasing Curtiss from ground level, the New York Times had chartered a special train to cover the event. Inside, it carried Curtiss’s wife, a support team, and a pool of excited reporters. As the locomotive sped down the rails of the New York Central’s Hudson River Line, Curtiss’s wife waved a handkerchief at her husband. One of his assistants unfurled an American flag in the rushing wind. It was the first time in history that an airplane and a locomotive had traveled side by side.

Together, Curtiss’s Albany Flyer and the patriotic train made quite a scene. “It was like a real race,” Curtiss recalled, “and I enjoyed the contest more than anything else during the flight.”

On the final leg of the flight into New York City, a crowd of thousands gathered to watch Curtiss at the northern end of Manhattan. Seeing an airplane for the first time, observers struggled to describe the sight and sound of Curtiss flying overhead. “The drumming of the motor sounded like the belligerent humming of an angry wasp,” said one witness. Down on the Hudson, the constant armada of ships that surrounded Manhattan blasted their whistles and fog horns, giving the aircraft a “hearty, if inharmonious, welcome” to New York.

Instead of flying directly to his original destination on Governor’s Island, Curtiss made an abrupt turn and doubled back up the Hudson River. He found an open stretch of grass at the northernmost tip of Manhattan (today Inwood Hill Park) and brought the aircraft to earth. This was the moment when Curtiss technically made history.

The aviator and his rubber pants were the first to complete what everyone at the time considered a “cross-country” flight. To modern air travelers, 150 miles seems like a short hop. In 1910 the crossing of this impossibly long stretch of terrain garnered wall-to-wall media coverage and front-page headlines. The conquest of such a great distance by air proved the concept for all future long-distance airmail and passenger service. Curtiss’s aircraft could do more than fly in circles like the Wright brothers’ contraption. His innovation could take him practically anywhere.

After landing his aircraft on Manhattan proper, Curtiss found a telephone and called in his achievement to the New York World to officially claim Pulitzer’s prize money. Then he inspected the flaps and wires of his aircraft. They were all in working order, so he sailed back into the air for a salutary victory flight around the island of Manhattan. It was a scene that New York would not soon forget.

Word of the flight had swept across the city. New Yorkers ducked out from church services. Some closed their shops. Curtiss gave everyone a show.

Flying low over New York, he buzzed Grant’s Tomb at two hundred feet and edged above the masts of passenger steamers and cargo ships moored along the Hudson River. He flew so low that the skyscrapers along New York’s rising skyline rose above the height of his aircraft. In Battery Park alone, ten thousand people scurried to the waterline to catch sight of Curtiss’ “Albany Flyer” as it rounded the southern tip of Manhattan. Included among them was a photographer who captured Curtiss on film just as he buzzed above the Statue of Liberty. The camera froze him in time like a wasp in gray and silver amber.

The incredible flight of Curtiss would ultimately succeed. Thanks to his prize money, the pioneering aviator sustained his legal fight against the Wright brothers. The original inventors of powered flight wasted too much of their energy on litigation instead of further innovation. Hard-charging inventors like Curtiss were poised to leave them far behind. And for one spectacular moment, he owned the skies.

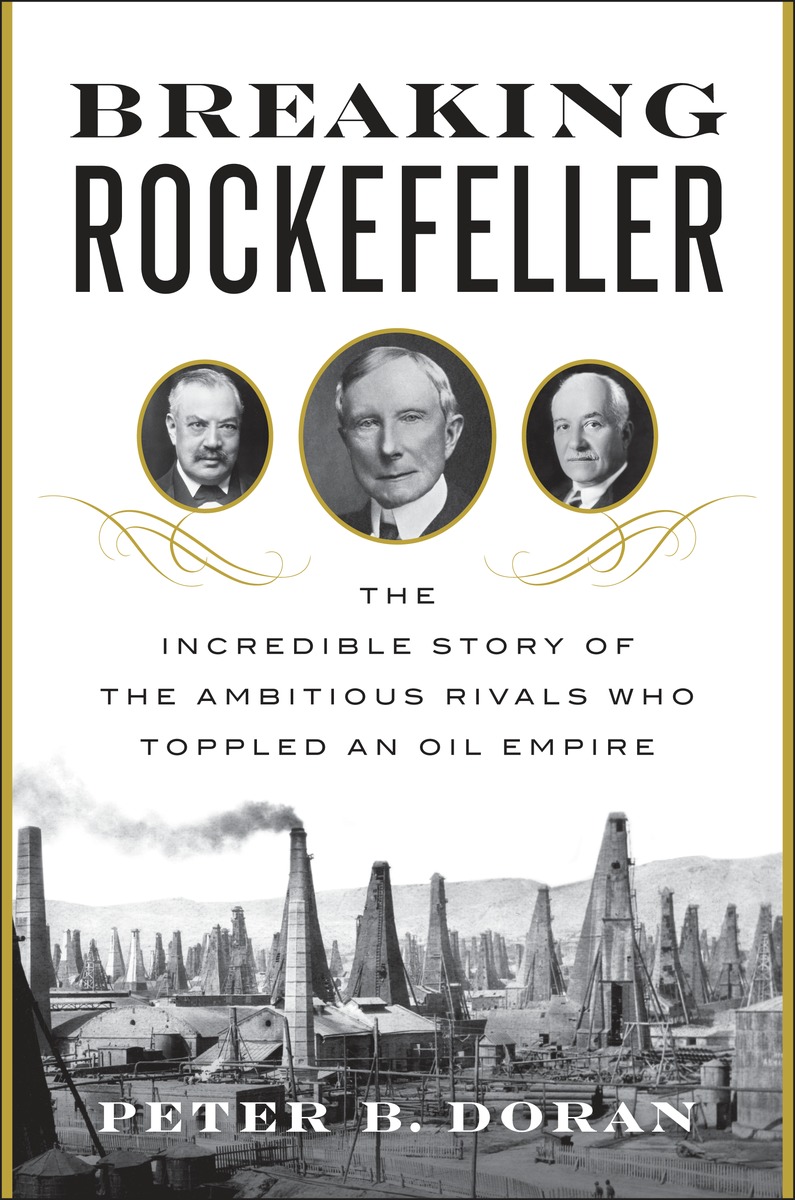

Excerpt from Breaking Rockefeller: The Incredible Story of the Ambitious Rivals Who Toppled an Oil Industry by Peter B. Doran, published on May 24, 2016 by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Peter B. Doran, 2016.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com