Just as Lyndon B. Johnson’s sudden ascension to the presidency due to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was unexpected, so was the impressive productivity and success of his first year in office.

The former Democratic senator from Texas was an exceedingly adept politician, pushing through major legislation and winning an election during a tumultuous time for the country. A cunning and complicated figure, Johnson’s character still intrigues today — just look at the popularity of Robert A. Caro‘s impressively thorough series of biographies, or the Broadway play based on LBJ’s first year in office, All the Way. An adaptation of that Robert Schenkkan play premieres on Saturday on HBO.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Before you tune in to watch Bryan Cranston as LBJ and Anthony Mackie as Martin Luther King Jr., brush up on the major moments of Johnson’s first year in office. Taken from the TIME archive, these stories give a narrative of the year that was written as it happened:

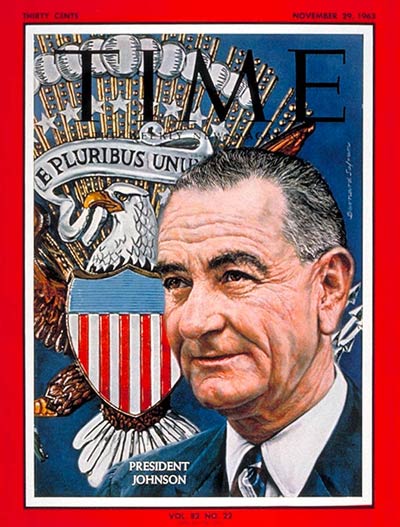

Oath of Office Here’s an account of Vice President Lyndon Johnson taking the Oath of Office aboard Air Force One, just 98 minutes after John Kennedy was declared dead, from a Nov. 29, 1963 write-up in TIME titled “The Transfer of Power“:

The plane’s sweltering, gold-carpeted “living room” was crowded with 27 people. At Johnson‘s right was his wife Lady Bird. Behind them ranged White House staff members; Larry O’Brien and Kenneth O’Donnell were in tears; the shirt cuffs of Rear Admiral George Burkley, President Kennedy’s personal physician, bore bloodstains. Federal District Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a trim, tiny woman of 67 whom Kennedy had appointed to the bench in 1961, pronounced the oath in a voice barely audible over the engines. Johnson, his left hand on a small black Bible, his right held high, repeated firmly: I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States. So help me God.

The First Order. The President leaned forward, kissed Lady Bird on the forehead. Mrs. Johnson turned to Jackie, held her hand and said: “The whole nation mourns your husband.” Dallas Police Chief J. E. Curry stepped up and advised the widow: “God bless you, little lady, but you ought to go back and lie down.” Replied Jackie: “No thanks, I’m fine.” Minutes later Johnson gave his first order as President of the United States. “Now,” he said, “let’s get this thing airborne.”

MORE: Bryan Cranston Talks Walter White, LBJ and His Own Political Ambitions

Hitting the Ground Running In the Dec. 13, 1963 issue, the magazine assessed the new president’s priorities:

CIVIL RIGHTS. Day after day, prominent Negro leaders such as James Farmer of CORE, and Whitney Young, executive director of the National Urban League, went to the White House to discuss the stalled civil rights bill and job discrimination. When Dr. Martin Luther King called, American Nazi Party members shuffled along Pennsylvania Avenue in storm-trooper outfits, carrying placards inscribed AH WANTS TO SEE DEE PRESIDENT TOO.

SPENDING & TAXES. Through the week, Budget Bureau officials trooped into Johnson’s office and left, as one of them described himself, looking “grim and tight-lipped.” To make Congress more amenable to a tax cut, Johnson was striving to cut expenditures for fiscal 1965, but he finally conceded that the budget would probably run in the neighborhood of $102 billion, thus would be the first to pass $100 billion.

UNEMPLOYMENT. With America’s jobless totaling 4,000,000, Johnson said he hoped to increase employment from the present level of 70 million to 75 million, urged labor and business leaders to “roll up your sleeves, stick out your chins and let it be known you are in this fight.”

Wheeling and Dealing By early 1964, the Revenue Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act were both moving ahead—to the surprise of many. As explained by this piece called “The Skipper & the Ship” from TIME’s Feb. 14, 1964 issue, some wondered whether Kennedy or Johnson deserved more credit:

In the House the civil rights bill was sailing through virtually unscathed; in the Senate the $11.6 billion tax cut was approved, and moved on toward conference committee.

Both actions followed a gale of White House phone calls to Capitol Hill. As Lyndon Johnson’s admirers saw it, the President deserved all the credit for breaking up the legislative ice jam. Others, however, insisted that Lyndon’s poking and prodding had little to do with it, that President Kennedy had already laid the groundwork for congressional action. The truth lay somewhere in between.

A Shining Moment LBJ signing the Civil Rights Act into effect on July 2, 1964. TIME framed the landmark legislation with the story of 13-year-old Eugene Young getting a haircut at a barbershop that had refused him the day before:

In the barbershop of Kansas City’s Muehlebach Hotel, a 13-year-old Negro boy, Eugene Young, hopped into a chair, opened his fist to display two $1 bills, and ordered a haircut. Without hesitating, Barber Lloyd Soper covered the lad with a white apron, took out his clippers and went to work.

Only the day before, Eugene had been refused service in the same shop. But in the intervening 24 hours, the most far-reaching civil rights bill in U.S. history had become the law of the land — and, as the Negro boy climbed into the chair, the time of testing had begun.

MORE: What Martin Luther King Really Thought About Lyndon Baines Johnson

Election Elation All the while, Johnson had been campaigning against renegade Republican Barry Goldwater. In November, he clinched the presidency in his first election to the position he already held, with 61.05% of the popular vote — setting a new record. From TIME’s Nov. 4, 1964 extra election issue:

To many who watched him, Lyndon Johnson’s mien was a fascinating thing to see. The man who was President-by-accident had suddenly realized that he was now President-by-choice, an achievement gained by whatever forces were at work for him during the campaign, but gained, nevertheless, on his own. Thus, as he stepped before the TV cameras at the Municipal Auditorium at 1:40 a.m., he spoke as a man confident of his powers to lead.

“Tonight,” he said in reserved tones, “we must face the world as one. Tonight our purpose must be to bind up our wounds, to heal our history, and to make this nation whole. This victory is a tribute to the program begun by our beloved President John F. Kennedy. It is a mandate for unity. It will be a Government that provides equal opportunity for all and special privileges for none. It is a command to build on those principles and to move forward toward peace and a better life for all our people. I promise the best that is in me for as long as I am permitted to serve. I ask all those who supported me and all those that opposed me to forget our differences, because there are many more things in America that unite us than divide us … We will be on our way to try to achieve peace in our time for our people and try to keep our people prosperous. I would like to leave you tonight with the words of Abraham Lincoln: ‘Without the assistance of that Divine Being who ever attended us, I cannot succeed. With that assistance, I cannot fail.'”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Julia Zorthian at julia.zorthian@time.com