The bison has been named America’s first national mammal, after the President signed the National Bison Legacy Act on Monday, the culmination of a four-year push by a coalition of over 60 organizations, businesses and Native American tribes. With the President’s signature, the measure will mean that the bison joins the bald eagle as an official animal symbol of the United States.

(For those tempted to whip out a banjo and start singing “Where the buffalo roam” from “Home on the Range,” note that bison and buffalo are different animals, even though Americans use the names interchangeably. The National Parks Service says early explorers in North America confused bison for “old world buffalo” — Asian and African buffalo — but bison have large shoulder humps and shorter horns.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The designation aims to “prevent” the nearly half a million North American bison “from going extinct and to recognize the bison’s ecological, cultural, historical and economic importance to the United States,” according to Cristián Samper, President and CEO of the Wildlife Conservation Society.

The American plains bison, however, is not an endangered species. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the wild population of plains bison—with the memorable scientific name Bison bison bison— numbers 20,504. (The wood bison, Bison bison athabascae, which really is much less common, is a separate subspecies.)

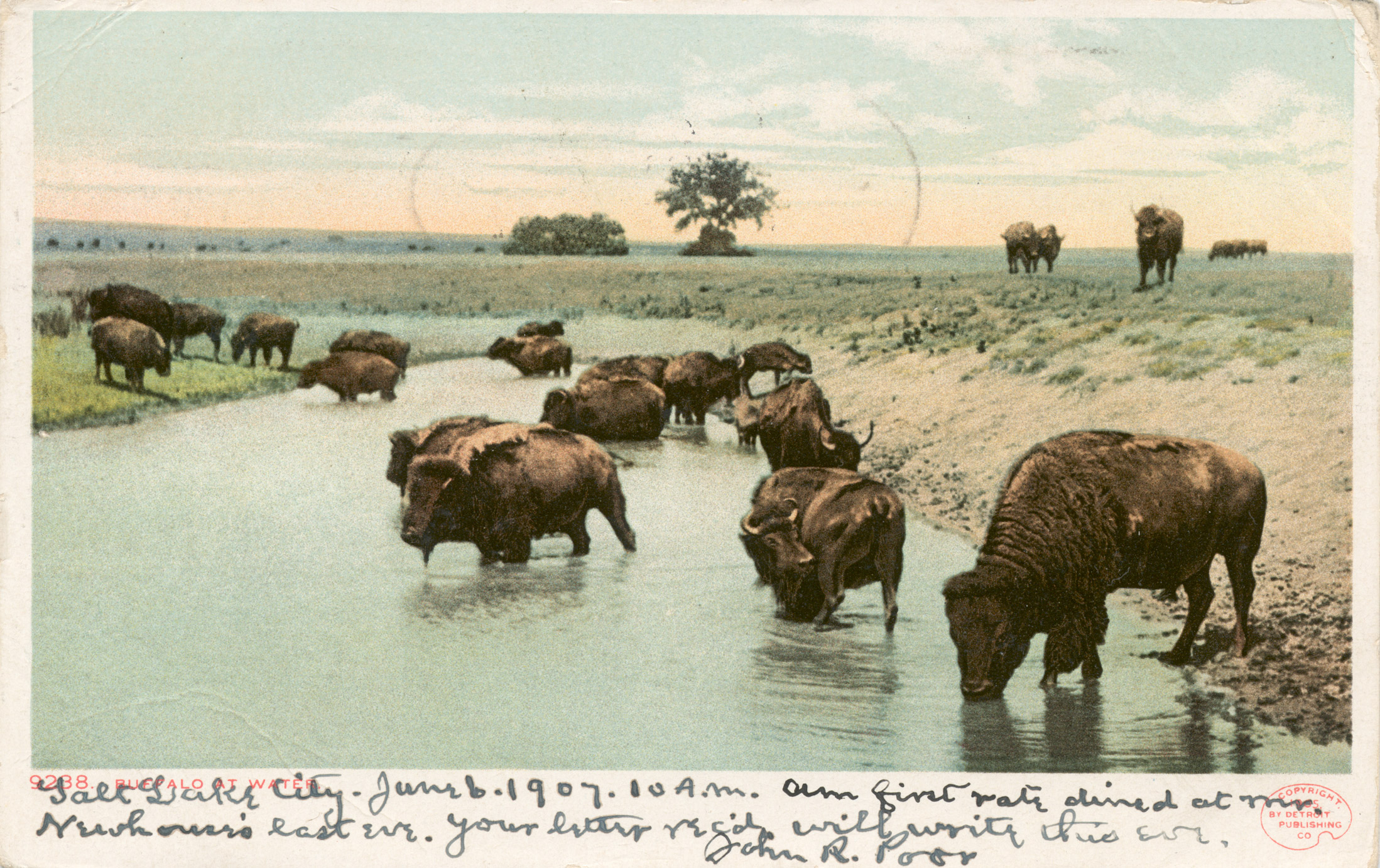

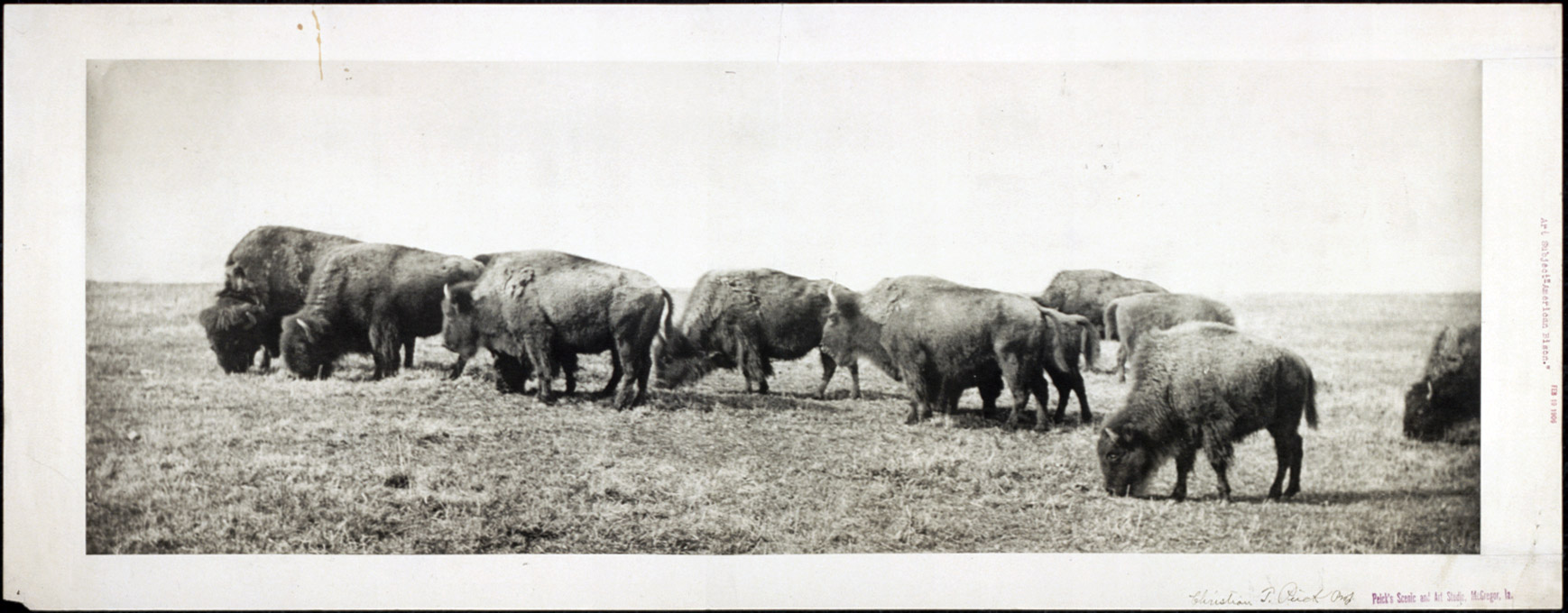

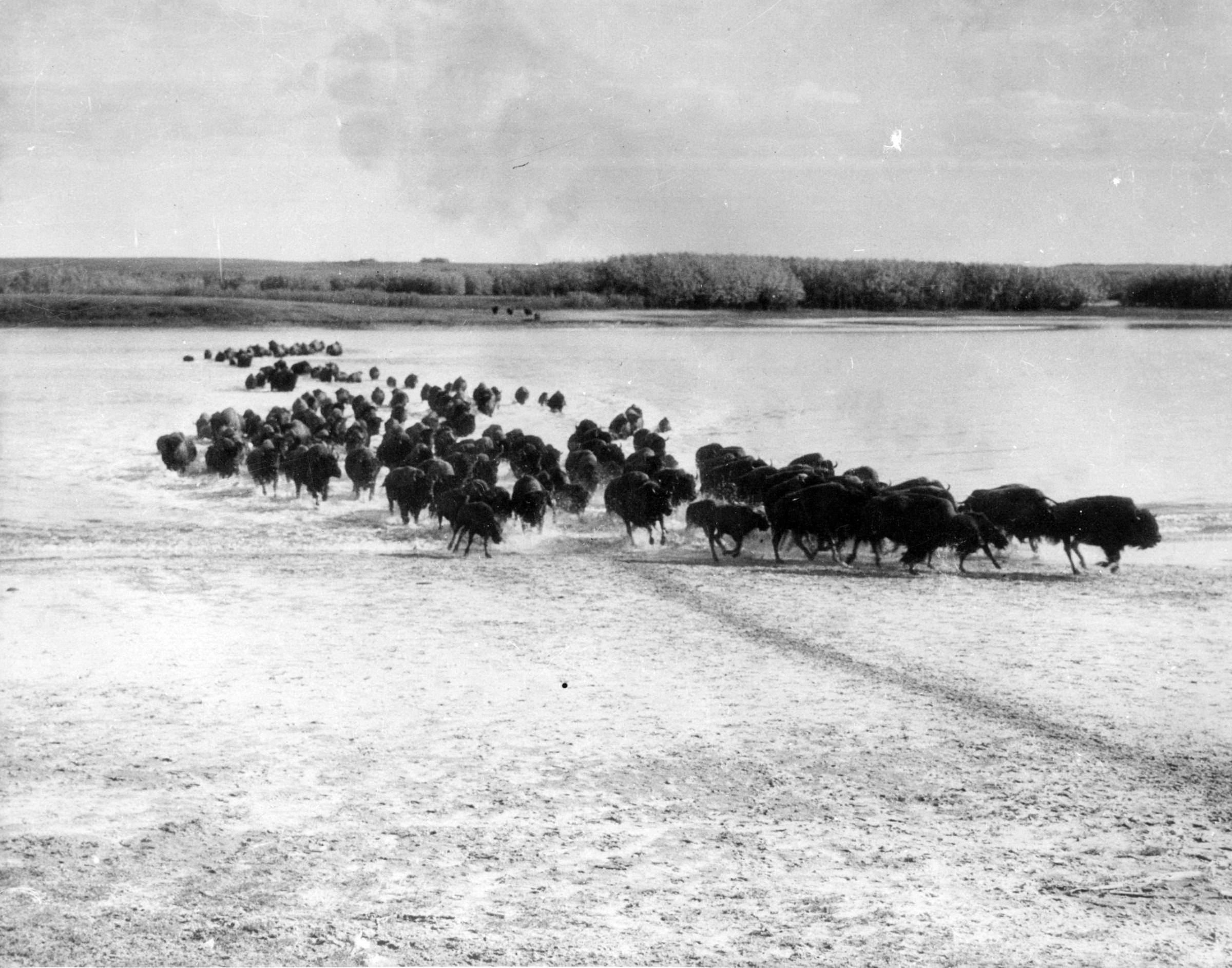

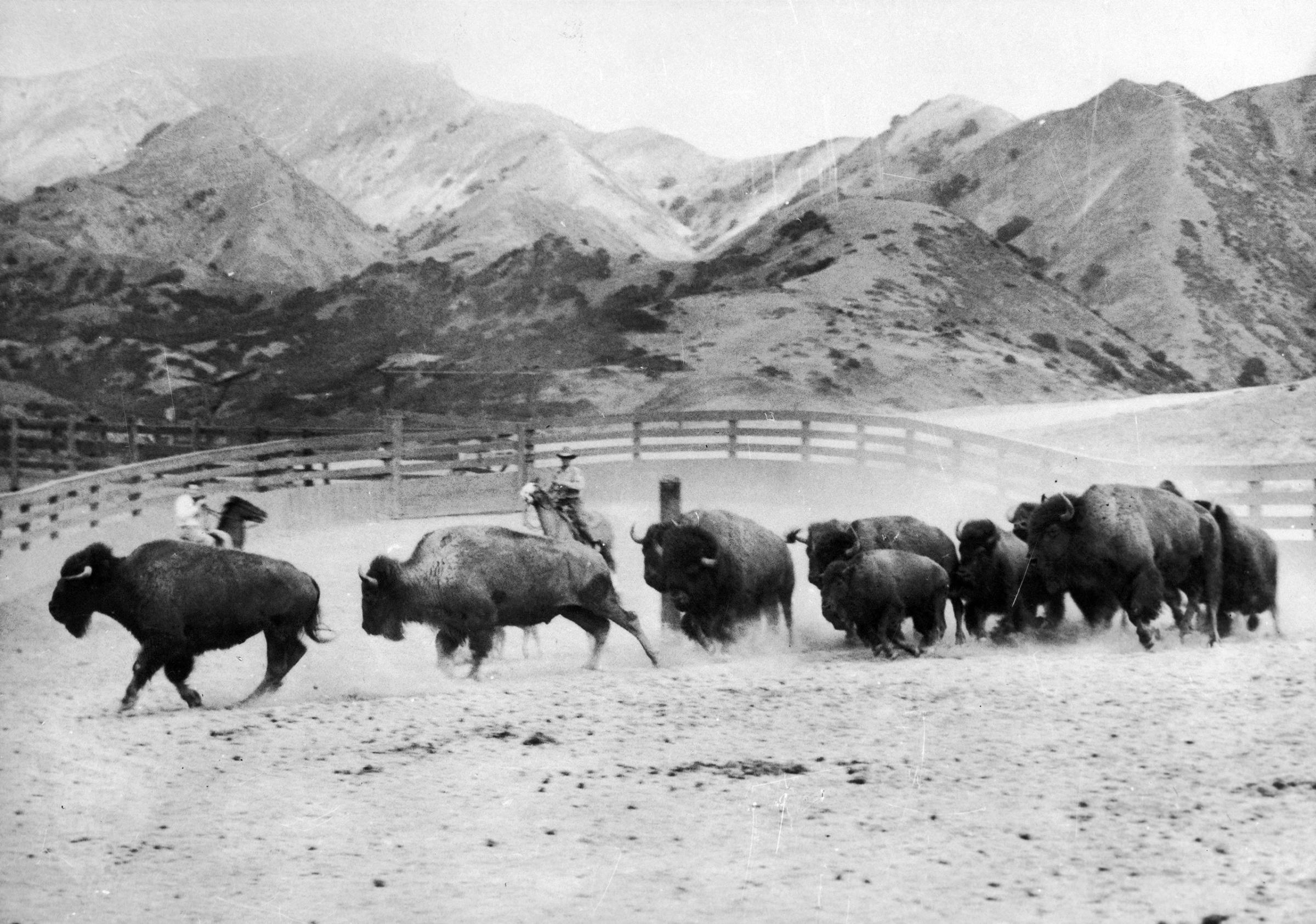

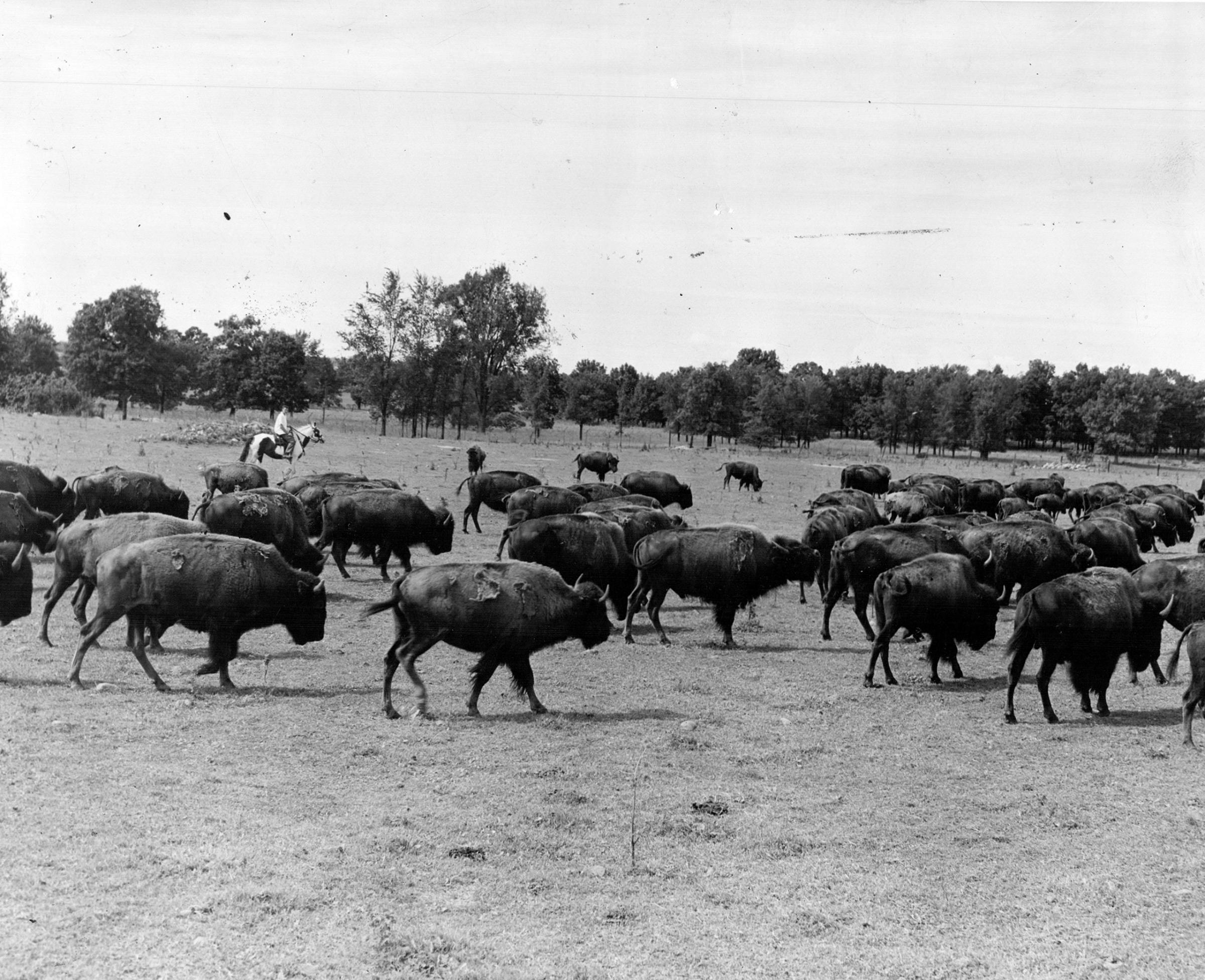

That’s not to say American bison wasn’t once on the brink of extinction. In the 1500s, about 30 million bison are said to have roamed in North America, but by the late 1800s, their numbers dropped to less than 1,000, likely due to a combination of human actions and climate change. Riding horses made it easier for humans to hunt them throughout the 1700s, until they started starving to death when an 1841 deep freeze iced over the prairies so the bison couldn’t eat the grass, as TIME previously reported. Bison hunts also expanded in response to increased demand for leather, becoming more efficient as better guns were invented and steam power enabled the faster, cheaper transportation of hides.

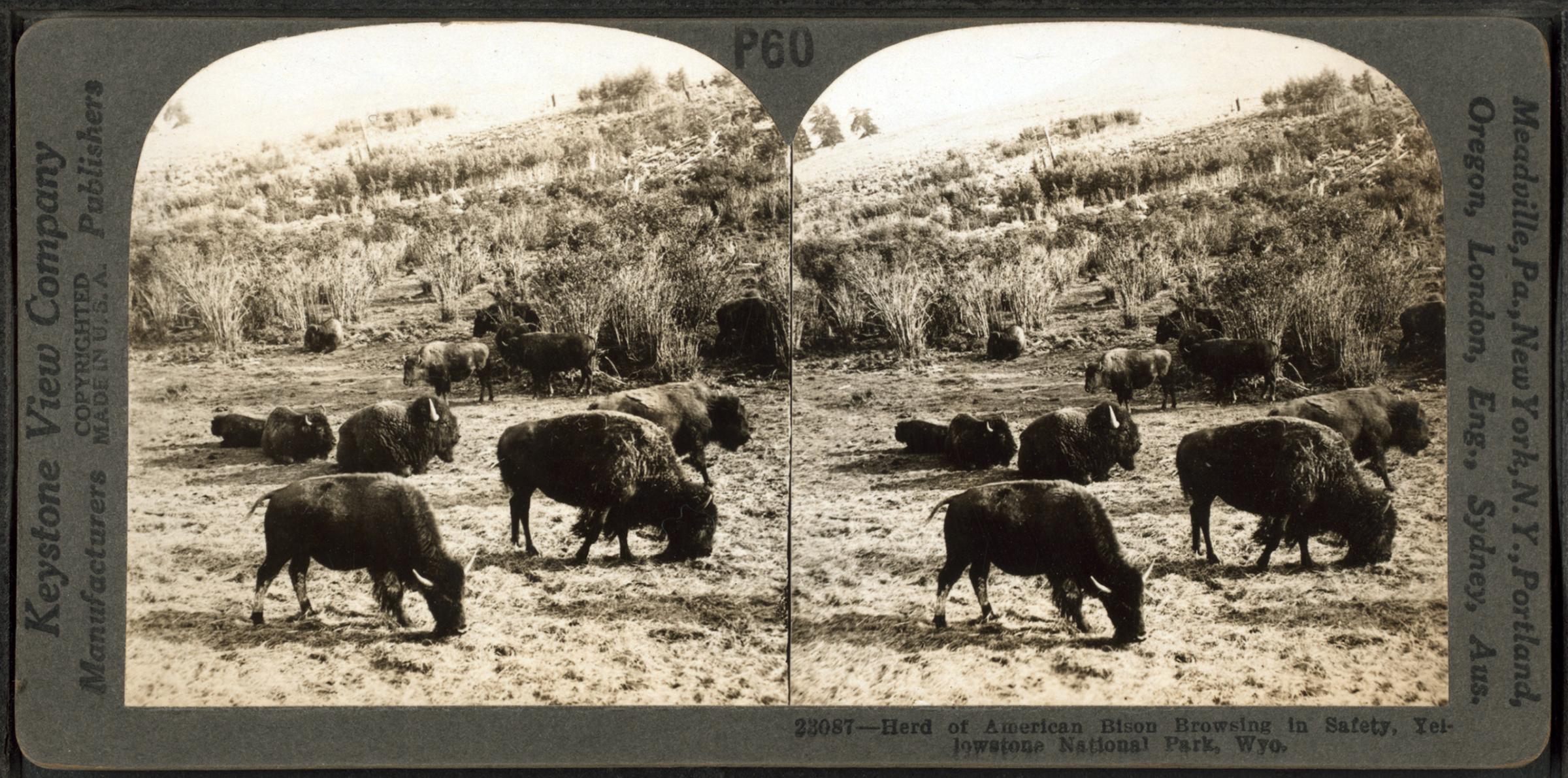

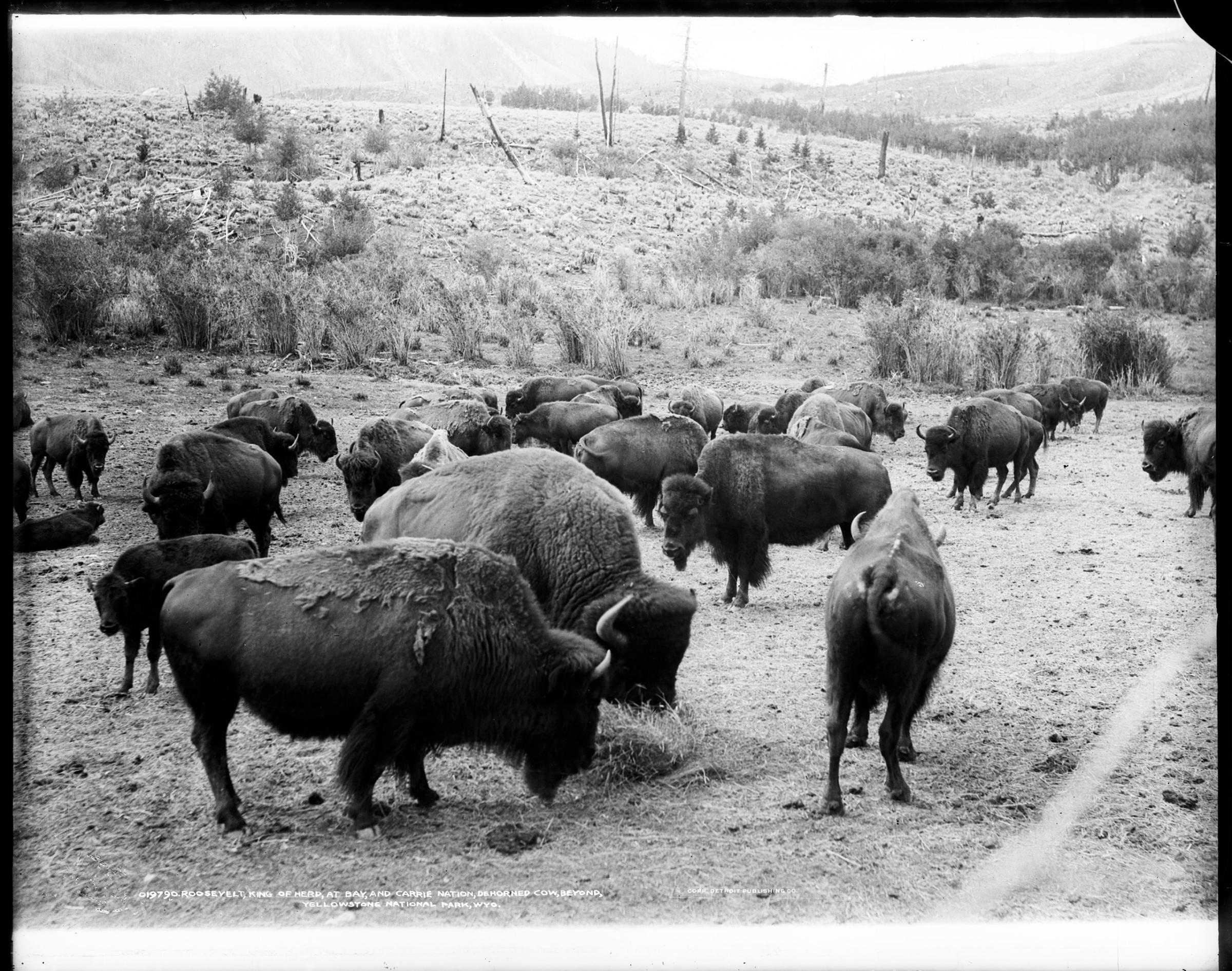

See Majestic Historical Photos of the U.S.’s New National Mammal

While some private ranchers rounded up some of the survivors to start small herds in the late 19th century, the Parks Service traces the beginning of a “concerted national effort” to preserve the species to Dec. 8, 1905, when the American Bison Society was formed by 16 people—including Theodore Roosevelt and William Hornaday, the first director of the New York Zoological Park (now known as the Bronx Zoo). Fifteen captive-bred bison were transferred from the Bronx Zoo to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, the oldest managed wildlife facility in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife system.

But, paradoxically, it was not just a desire to keep bison alive that finally prevented their extinction.

“Sometimes you have to eat an animal to save it,” as TIME explained in a 2007 profile written at a moment when bison were considered the fastest-growing sector of the meat business. By one 2011 count, the number of farmed bison, in herds meant for commercial purposes, is nearly 20 times the size of the “conservation” population. As the magazine summed up why private ranchers are key to the survival of the species:

[I]t wasn’t until the ’70s, when ranchers began acquiring bison with an eye toward encouraging a boutique meat market (Native Americans, Old West enthusiasts, health nuts), that the species rebounded in numbers significant enough to ensure genetic diversity and protection against disasters like that 1841 freeze . . .

The ranchers care for bison because they can make money selling their meat. And so bison are flourishing again because they have the evolutionary advantage of tasting good and having survived to a time when we all need to eat leaner. We win, and bison win. Of course, the individual bison we eat lose, but the nature of the paradox is that most never would have a chance at life at all if we didn’t provide a reason for their husbandry.

Read the full story from 2007, here in the TIME Vault: Why the Buffalo Roam

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com