Annette Gordon-Reed wrote the following dissent in response to the recommendation to remove the Harvard Law School shield. The university announced its decision to retire the shield on Monday.

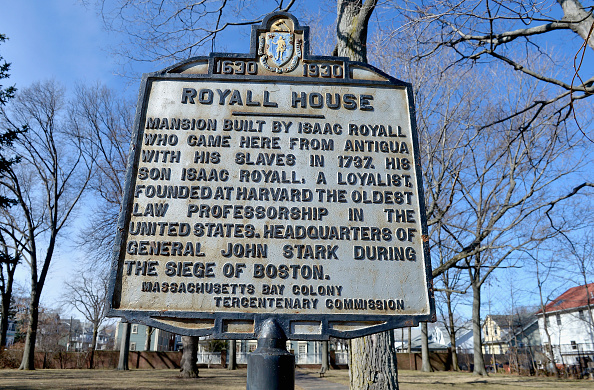

I write to express a different view about whether the Law School should change its shield, mindful of the heartfelt sentiments expressed on the other side and cognizant that mine is the minority view. To state upfront, from the moment I learned, some years ago, about the wheat sheaves’ connection to the Royall Plantation and the plantation’s connection to the Law School, the burning question for me has been, “What would be the best and easiest way to keep alive the memory of the people whose labor gave Isaac Royall the resources to purchase the land whose sale helped found Harvard Law School?” And when I say, “keep alive,” I do not mean keep the Royall connection as a story that we tell just amongst ourselves when students first enter the Law School— although we should obviously continue to do that. “Keep alive” means to be unrelentingly frank and open with the whole world, now and into the future, about an important thing that went into making this institution. Maintaining the current shield, and tying it to a historically sound interpretive narrative about it, would be the most honest and forthright way to insure that the true story of our origins, and connection to the people whom we should see as our progenitors (the enslaved people at Royall’s plantations, not Isaac Royall), is not lost.

Why do I think the current shield can—and should—be made to carry forward the story of, and our connection to, those enslaved at the Royall Plantation? For nearly its entire existence, the shield has sent no singular public message or had any function besides announcing the “arrival” of the Harvard Law School, generally viewed positively as one of the premier educational institutions in the world. Therefore, the shield is not, as I have heard it said in formal conversations about this issue and in informal ones, in any way akin to the Confederate flag or the Nazi flag. Individuals can say they feel it is, but if they do they ought to think seriously about, and associate themselves with, the problematic implications of that position.

The Confederate Flag came into existence as part of a clear and unambiguous project: it was a battle standard flown against the United States of America in order to protect African-American chattel slavery by means of a war that took half a million lives. In the years since the Civil War, that flag has been hauled out to intimidate black people and to serve, at key moments, as a symbol of opposition to racial equality. By this point in our history, these associations are too strong to totally divest that flag of its original meaning, and the very public meaning it has been given in the decades after the war. On the Nazi flag, I should not have to belabor why an image of wheat, an image that has appeared on many shields and crests for centuries, and was even on America’s penny, cannot be equated with a flag that sent armies marching across Europe, provoking a conflagration that killed over 60 million people worldwide.

The shield, it should be added, contains no physical representation of Royall, which would be an unambiguous celebration of the man himself. It is, thus, not like the statue of Cecil Rhodes that has roiled Oriel College, Oxford and sparked the movement copied here at HLS. As lawyers, we are trained to distinguish situations—to notice how this particular thing is not like that other particular thing—and to find the reasoning about them that should flow from those differences. We can apply that here. Until Dan Coquillette’s excellent work on the history of HLS, most people did not know of the connection between the Royalls, the sheaves, and the Law School. Since the shield’s adoption in the 1930s, any HLS graduates who have paid attention to the shield (and I am one) have been forced, by the obscurity of the shield’s origins, to make their own internal meaning of the image. It has carried no one specific and dominant association. This is nothing like the situation with the more famous symbols mentioned above.

Whatever the shield has (or has not) meant personally to thousands of HLS students and graduates, those students and alums have made the school’s modern public reputation in the decades since the shield was adopted. Current students and faculty benefit from what the Law School’s graduates have done in the 20th and 21st centuries. Many of our graduates have been at the forefront of movements for justice and equality, and have exhibited a profound commitment to public service. They did this without any knowledge of the sheaves’ provenance or any intent to countenance Isaac Royall’s way of life. What they have done over the past 80 years, particularly in very recent decades when the shield has been the most visible symbol of HLS, certainly creates a stronger source for defining what the shield means than whatever the Royall family may have been thinking about the sheaves centuries ago. By their accomplishments, actions, and work, HLS students and alums have made a new thing of the shield, and their efforts should not come second place to Royall and his family.

The enslaved at the Royall Plantation and the graduates of Harvard Law School should be tied together as they have been without our knowledge for so many years, and as they always will be whether we choose to hide that connection from the world or not. Disaggregating the benefit achieved from the labor of the enslaved—the money accrued from the sale of Royall land—from the “burdens” of being constantly reminded of from whence that money came, and of letting people outside the community know from whence it came, would be an abdication of our responsibility to the enslaved and a missed opportunity to educate. We have been told that a number of the inhabitants of Antigua (the site of the Royall Plantation) are enthusiastic about the association with the Harvard Law School. I have not talked to them myself, but I am almost certain that any enthusiasm expressed, by however large or small a number, was not born of reverence for Isaac Royall. It is far more likely that these descendants of enslaved people understand what 60 years of slavery historiography have taught us: the Royall Plantation was not about Isaac Royall. It was primarily about the enslaved men, woman, and children whose forced labor enriched people like the Royalls and helped fuel the wealth of Western nations.

So, what is to be done? I understand that getting rid of the shield altogether may seem less confrontational and the more conservative option. But this is a moment for daring and creativity. We are in the midst of an explosion of interest in and scholarship about slavery in New England. As an educational institution, HLS should be among the leaders of the effort to explicate this history. We should be at the forefront of this, using our own history as a guide. We are coming upon our 200th anniversary. This would be a perfect time to re-dedicate the Law School and the shield—making explicit our debt to the enslaved and our commitment, in their memory, to the cause of justice. Though this could be accomplished without changing the shield, if it is to be changed, perhaps the word “iustitia” (justice) could be placed directly beneath the tablets spelling out “Veritas”, and the sheaves made slightly smaller to accommodate the added word. This would tie the past to the present and to the future. Referencing how the law school began would be combined with the spirit that has motivated HLS since the adoption of the shield.

This matter should not end with a ceremony. Brown University has moved forthrightly in the wake of the uncovered history of the Brown family’s slave trading activities. Perhaps we might study their model, taking only the things that are most useful to our particular circumstances. We might actually do some research, and acquaint ourselves with what is going on with slavery studies and how other public institutions memorialize it. Believe me, there is a lot out there. Of course, it would be near impossible for Brown to disassociate itself from the Brown brothers, and we are not in so stark a position with our shield. But a measure of character is when we do the right (as outlined above) and difficult thing when we do not have to. I say “difficult” because it is clear that, for many, there is great discomfort—disgust even—at the thought of looking at the Harvard shield and having to think of slavery. A number of people have expressed this sentiment to me face-to-face and in written comments. Of course, I think differently about this: people should have think about slavery when they think of the Harvard shield; but, from now on, with a narrative that emphasizes the enslaved, not the Royall family. I am aware that being required to do that will provoke strong and unpleasant feelings. But it is vital to learn how to govern strong and unpleasant feelings so that one can be ready to be of service to other people and to purposes outside of (and even more important than) one’s personal feelings.

When he became Dean of Harvard Law School, Erwin Griswold wanted to have a motto for the school – some admired lines from Chaucer. Though the motto was never formally adopted, the words are apt:

For out of old fields, as people say,

Comes all this new grain from year to year;

And out of old books, in good faith,

Comes all this new knowledge that people learn.

Thanks to historians, we have “new knowledge” that we are joined in history to a group of people entrapped in the tragedy of the Atlantic slave trade. This also joins us to the larger American story of slavery. We should take this knowledge and run with it, not away from it. I end where I began: the larger purpose outside of our own personal feelings is to marry the memory of the injustice done to the people enslaved on the Royall plantation to Harvard Law School’s modern commitment to justice and equality through a well-known symbol that connects both.

Annette Gordon-Reed is the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History, Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and a Professor of History at Harvard University.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com