Watching the Oscars in light of the controversy over racial inequality reminded me of the difference between how society views privilege today compared to in the past. There was a time when, for many at least, privilege meant a life of service. Many of the wealthy who built this country had a code of honor that seems unimaginable today.

If you doubt me, read this fascinating passage from the autobiography of a preeminent historian of the 20th century, John Lukacs:

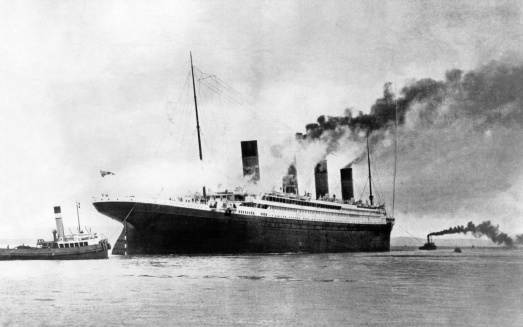

Of the many differences between the movie ‘Titanic’ and history, one in particular is telling. In the movie, as the ship is sinking the first-class passengers (all third-class human beings) scramble to climb into the small number of lifeboats. Only the determination of the hardy seamen — who use guns to keep the grasping men at bay — gets the women and children into the boats.

In fact, according to survivors’ accounts, the ‘women and children first’ convention was observed with almost no dissension, particularly among the upper classes. The statistics make this plain. In first class, every child was saved, as were all but five (of 144) women, three of whom chose to die with their husbands. By contrast, 70 percent of the men perished. In second class, 80 percent of the women were saved but 90 percent of the men drowned.

The men on the first-class list of the Titanic virtually made up the Forbes 400 of the time. John Jacob Astor, reputedly the richest man of his day, is said to have fought his way to a boat, put his wife in it and then stepped back and waved her goodbye. Benjamin Guggenheim similarly refused to take a seat, saying: ‘Tell my wife … I played the game out straight and to the end. No woman shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward.’ In other words, some of the most powerful men in the world adhered to an unwritten code of honor — even though it meant certain death for them. The movie makers altered the story for good reason: no one would believe it today.

In our day, we often associate wealth with advantage or flamboyance, but rarely with service. The renewal of this ideal is among the most important social changes that we could encourage. As the world grows more unequal economically, the decency and largesse of the privileged is both morally and socially vital.

The rich are undertaking new philanthropic initiatives, and in general there seems to be a growing philanthropic ethos. But the underlying philosophy of wealth used to be that it was a God-given benefit and had to be used for honorable purposes. After all, even the self-made success relies upon the infrastructure of society, the help of others and innate talents to succeed. No one makes it alone—as Mark Twain said: The self made man is as likely as the self-laid egg.

If we can keep the recognition that the Astors and the Guggenheims had—that wealth is a call to give—that success is expressed in service, and that we all owe each other a chance to have a chance, then perhaps despite the storms, we can save the ship.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com