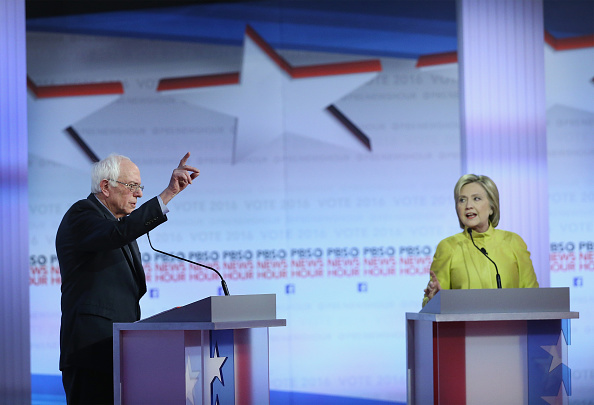

In Hillary Clinton’s opening remarks at Thursday night’s Democratic debate she highlighted her focus on women’s rights, speaking about the importance of “guaranteeing that women’s work finally gets the equal pay that we deserve.” Later in the event she returned to the topic of gender, effectively weighing in on a dispute that has raged like wildfire over the past week.

The argument, in a vastly simplified nutshell, goes something like this: Some journalists and Clinton supporters suggest so-called “Bernie Bros” have abandoned their liberal principles in a feverish obsession with promoting their candidate at any cost, and have sunk to the level of an opposition they claim to despise by using sexist tactics and online abuse. Some Sanders supporters claim this is a smear campaign based on cherry-picked social media examples that could be found by trawling through the supporter accounts of any major movement. They point to similar past accusations about “Obama Bros” as evidence that this argument will inevitably be used by Clinton supporters to score points by “playing the sexism card,” regardless of her opponent and his supporters’ behavior.

Some Clinton supporters suggest that female Democratic voters have a duty to vote for the first woman president to help secure a victory in a long and bitterly fought battle for gender equality that is far from over. Sanders supporters cry sexism at the notion of supporting any candidate based on gender alone and point out that Sanders has many female supporters, as if that somehow magically absolves his fans (male or female) of the potential for sexist social media abuse.

Clinton’s acknowledgement of the furore at the debate was prompted by a question about former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who had suggested young women should support Clinton using her oft-repeated mantra: “There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.”

At the debate, Clinton responded: “I have said many times, I am not asking people to support me because I am a woman. I’m asking people to support me because I think I am the most qualified, experienced, and ready person to be the president and the commander-in-chief.” But, crucially, she also added: “I have spent my entire adult life making sure that women are empowered to make their own choices, even if that choice is not to vote for me.”

What Clinton said was right, and it was true.

Rewards or payback are not the point. They can’t be. We can’t defend a woman’s right to state her opinions free from misogynistic attacks, but only as long as we agree with her. We can’t fight for women to have the vote but then dictate that they must use it to promote a specifically feminist agenda. And we can’t ignore the fact that different women’s feminist agendas might have different priorities and lead them to different candidates. For some feminists in the Milwaukee debate audience, the candidates’ responses about immigration, minimum wage or the criminal justice system may have held more pressing urgency than their rhetoric on equal pay.

But Sanders supporters also shouldn’t claim to care about equality and then stick their heads in the sand and try to airbrush out the misogynistic abuse a female candidate and her supporters are undeniably facing because they’re worried it might reflect badly on their preferred candidate. They shouldn’t use the fact that sexism has been a major problem in previous campaigns to dismiss the issue, or imply that current male candidates shouldn’t take responsibility when it happens in the ranks of their supporters. It is a particularly male and privileged position to focus on arguing about whether or not this is a new issue, and who should bear the blame for it, while women are experiencing abuse and coming up against sexist double standards at every turn.

The frustrating thing about so many of these familiar and repeated arguments is that they forego nuance in favor of political point scoring, and often miss the point entirely. The feverish attempts to distance Sanders from the issue of online abuse often run close to dismissing and denying women’s experiences and suggesting that the abuse itself is unimportant. When we see young women being pressured to vote for Hillary Clinton because she is a woman, we not only assign them an unfairly swollen burden of responsibility for the privilege of their vote, but also let young men (and indeed all men) off the hook. Seeing greater diversity in political representation shouldn’t be a women’s issue at all—we should demand that the consideration of diversity be a priority for all voters, not just those whose characteristics match those of a particular candidate. The “special place in hell” concept uncomfortably risks placing the burden for solving issues of structural discrimination at women’s feet, rather than demanding systemic change and universal condemnation of inequality.

Conversely, as Jessica Valenti has pointed out, to dismiss those who actively choose a candidate partly on the basis of their gender as irresponsible or sexist is to fail to acknowledge the importance and impact of representation; both at a policy level and for the sake of its influence on the next generations of potential political leaders.

The kerfuffle also risks alienating and insulting female liberal voters who might support neither of the front-running candidates. The tenor of this debate (particularly online) seems to assume that any young woman who has chosen to vote for either Sanders or Clinton is wildly in thrall to their every historical policy position and vote, rather than giving them the credit for having weighed a complex situation and made a complex decision. Funnily enough we don’t see young men’s voting habits being scrutinized and lambasted in the same way.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com