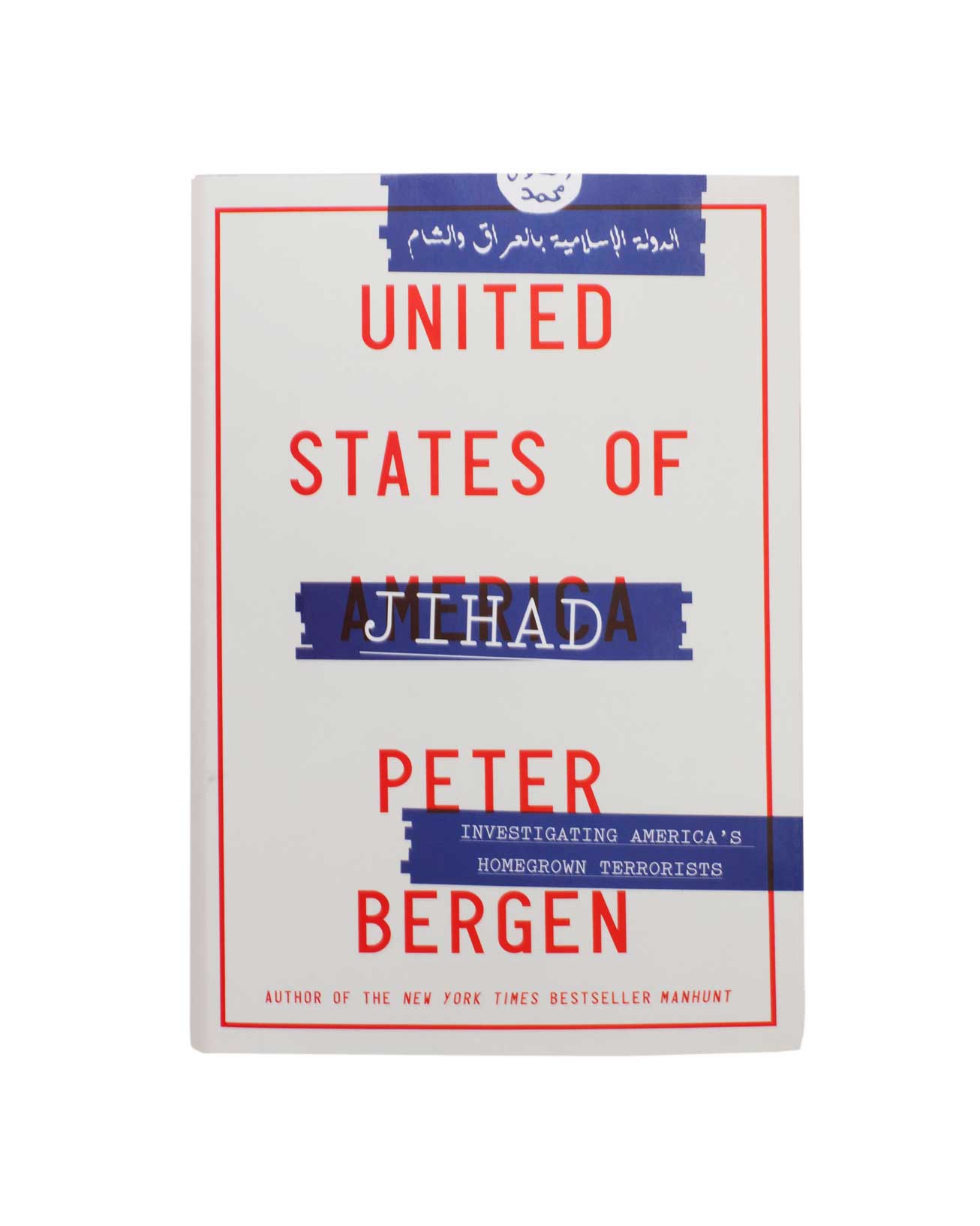

The people who know the most about terrorism are pretty much all on the same page, and in Peter Bergen’s United States of Jihad, that page is the last one. It’s where the author strives to put into perspective the sense of peril that has kept the reader turning the previous 279 pages, a pulsing urgency that propels TV series like Homeland, much of cable news and the smack talk of the Republican presidential field–this feeling that something’s going to happen, something terrible.

Except it’s probably not, Bergen concludes. There is terrorism, and there is fear of terrorism, and only one of those is actually rampant in the U.S. “I don’t worry about it very much,” says a former top counterterrorism official from the FBI, Philip Mudd, in the nuanced HBO documentary Homegrown, adapted from Bergen’s book. Andrew Liepman, a former No. 2 at the National Counterterrorism Center, lists bigger threats: obesity, cancer, gun violence. “But that,” he says, “doesn’t capture America’s imagination as much as the threat from ISIS.”

So here we all are, on the edge of our seats, when maybe we should be settled into the couch cushions–working it out with a counselor. Bergen points out that the enormous security apparatus put in place after 9/11 has prevented anything remotely similar from occurring since. Of 72 known plots, including a few of dubious inspiration, 56 were detected by law enforcement (44 with tips from Muslims). The death count from the few that succeeded narrowly trails the 48 people killed by right-wing extremists.

There’s drama in the cases Bergen relates at chapter length, but knowing what we already do, it’s nearly the vicarious sort produced by horror films and detective fiction. A decade ago, Garrison Keillor wrote that victory in the Cold War “left us feeling oddly bereft, so now we have embraced the War Against Terrorism, which nobody believes in–there is no rush to enlist–and yet the concrete barricades and the platoons of security at the airport do give us a sense of danger, which is satisfying.”

The anxiety is real, though, whatever its source. The beheadings of James Foley and Steven Sotloff awakened something that has only been amplified in the 17 months since, and now dominates all public concerns, polls say. Bergen is not the go-to guy on ISIS, or “punk jihad.” He’s more O.G., having made his bones interviewing Osama bin Laden in 1997. But he makes a highly reliable guide on the road to the present day, which turns out to be the information superhighway. U.S.-born terrorists followed logically from the arrival online of English-language jihadi literature, including sermons. The American-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki died by drone strike in 2011, but his teachings survive online and were absorbed by 87 of the 330 Americans charged with Islamic terrorism since 9/11.

Bergen also surveys the expert thinking on what makes a jihadi–a crucial evolution now that social media allow terrorists to groom recruits online. He ends up at Quantico, Va., where FBI profilers have developed promising tools to separate who’s all talk from who just might. If the assessments work, it would vindicate those who argued that, post-Afghanistan, countering terrorism should have been a job for law-enforcement and security services.

Instead, the U.S. invaded Iraq, blowing oxygen onto fading embers, and got ISIS. It pays to remember that the whole point of terrorism is to provoke an overreaction. (One jihadi handbook is titled The Management of Savagery.) As Bergen says, if 9/11 happened because we had our guard down, no one can argue that our guard is down now. It’s so far up, it may be obscuring our sight.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com