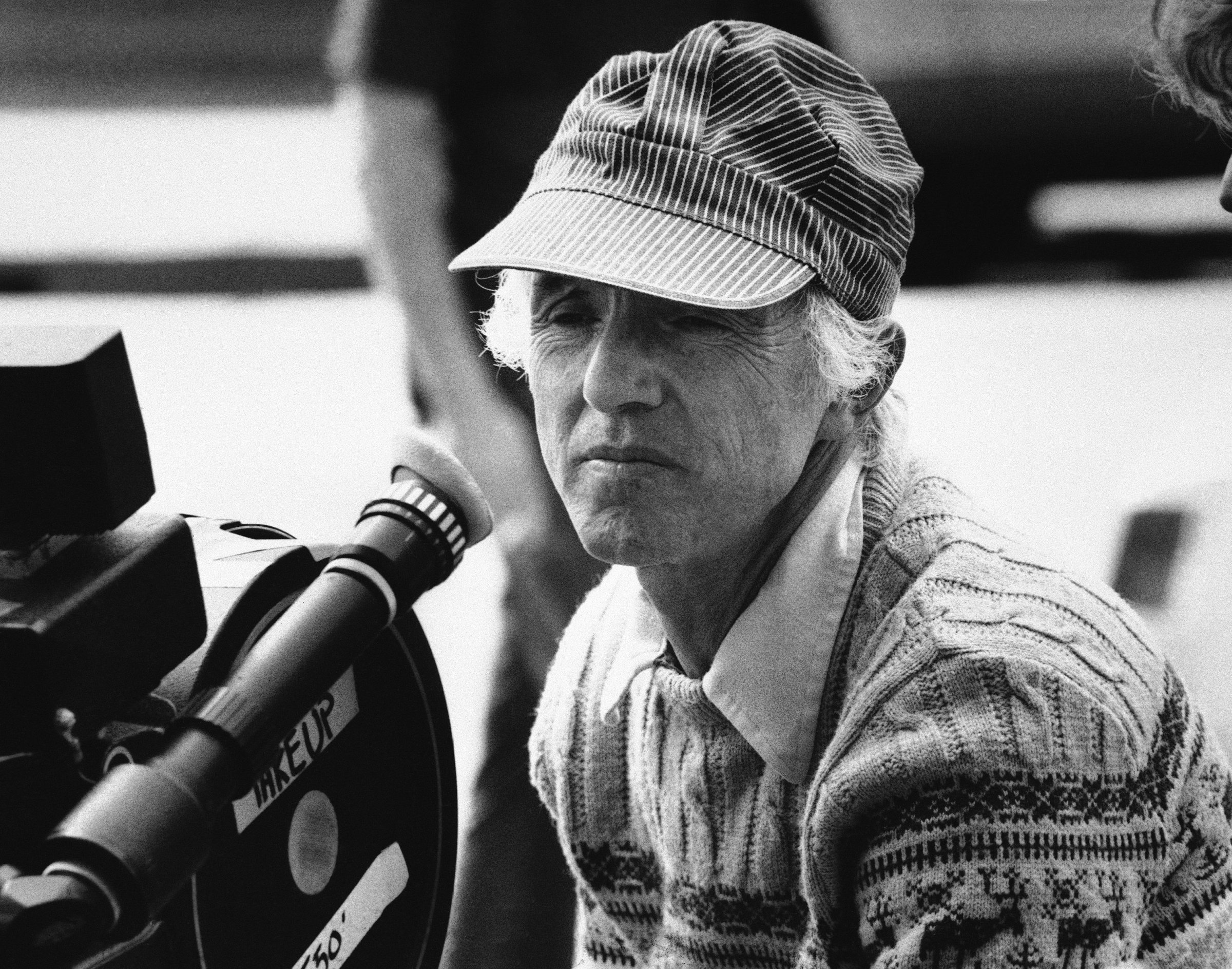

The cinematographer’s art isn’t just about using light creatively or developing a flashy, distinctive style: It’s about finding the right look for every story and still marking it with a subtle fingerprint. Master cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who died Sunday at age 93, had that down cold. For Mike Nichols’ 1966 Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor as a mutually destructive husband and wife, the satiny precision of Wexler’s black-and-white images sliced right through a disintegrating marriage, straight to the bone. A gorgeous-looking movie about hopelessly gnarled human relations, it earned Wexler an Oscar, the last one to be given specifically for black-and-white cinematography. Wexler also knew what to do with breezier popular entertainments: The 1968 heist romance The Thomas Crown Affair was a pop-art reverie swirled with cream, and Wexler shot the movie’s stars, Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway—looking luminous and glamorous yet also indisputably now—as if they were 1930s matinee idols whisked via time machine into a bouffant-and-miniskirt future.

But those are just two movies. During his long, vigorous career, Wexler shot many fiction features, documentaries and shorts (some 80 altogether), and made his mark as a director, too. His 1969 Medium Cool, starring Robert Forster as a TV news reporter who’s at first oblivious to the ethical issues attendant to his profession, was a scripted film shot during the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago: Wexler mingled fiction with documentary footage of the riots that broke out there. This approach wasn’t only artistically innovative—it also coincided with, and became a record of, a significant political flashpoint.

Throughout his career, Wexler was a passionate, vocal lefty, frequently working with director John Sayles (on films like the 1987 Matewan, which dramatized a real-life 1920 coal miners’ strike in West Virginia). He also made political documentaries like the 1976 Underground—co-directed with Emile de Antonio and Mary Lampson—which explored the activities of the radical, intensely reclusive Weather Underground. And he’d win his second Oscar for his work on the 1976 Bound for Glory, directed by Hal Ashby, a biopic of folk singer—and working-man’s hero—Woody Guthrie.

Wexler received five Academy Award nominations during the course of his career, but the value of the work he leaves behind can’t be adequately measured in official accolades. Wexler wasn’t nominated for his work on Norman Jewison’s 1967 In the Heat of the Night, starring Sidney Poitier as a detective from the north squaring off against Rod Steiger’s bigoted small-town Mississippi sheriff. The early scenes, in which Steiger needles Poitier in the sheriff’s office, have a sweaty, oppressive glow. Much later, in an extraordinary sequence set in Steiger’s drab, dismally furnished house, the two men begin to reach a tentative truce: As they talk about loneliness, among other things, their faces are bathed in lamplight that looks like a kind of benediction—at least until Steiger breaks the mood by growing surly again.

Another angle of the cinematographer’s art is knowing how to help shape a moment with color, light and texture, all of which Wexler does in In the Heat of the Moment. But he also knew what to do with faces, specifically Poitier’s. In his marvelous book Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, Mark Harris explains that Wexler, unlike most of his colleagues at the time, knew that white skin and black skin demanded different approaches when it came to lighting. Wexler used low light throughout In the Heat of the Night, in part to make sure Poitier’s facial features would always read clearly. In other movies, Poitier had often been overlit in a way that sabotaged the subtlety of his expression. “Wexler and Jewison,” Harris writes, “made sure that every unspoken thought that played across his lips and eyes would read on camera and be visible to moviegoers.” And that, maybe, is the most delicate facet of the cinematographer’s art: To make sure that even abstractions we can’t see, like thoughts and feelings, are always clearly visible. Wexler could do it all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com