Charlie Sheen’s announcement Tuesday morning on Today that he is HIV-positive came along with confirmation from his doctor that his viral load is undetectable and that he’s on a rigorous medication schedule—and, perhaps more notably, that he sees going public about his status as the beginning of “another chapter in [his] life.” It’s a marked difference from another celebrity press conference that took place almost exactly 24 years ago. The change in tone is clear evidence of the progress that has been made possible by a quarter-century of research.

Back in November of 1991, NBA star Magic Johnson’s announcement that he had tested positive was clearly marked as an ending, not a beginning. It was also a retirement announcement and, though he had not yet displayed symptoms and he maintained an upbeat tone during the press conference itself, the news did not go down easy. As TIME reported, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar “simply broke down and wept.” Though Johnson was not the first celebrity to have contracted the virus—the others ranged from Rock Hudson to NFL player Jerry Smith—he was notable for the extent of his fame, his outward appearance of health and his willingness to speak about what was, TIME could say without editorializing, “the saddest moment of his life.”

Though some treatments were available by that time, there was no concealing the fact that Johnson’s announcement was seen by many as advance warning of his impending death. (Nearly 25 years later, Johnson is very much alive.) In addition, it was a shock to a society that still believed, as TIME put it, that “AIDS was something that happened to ghetto dwellers, drug addicts or gays, not to middle- and upper-class folks who limited themselves to straight sex.” Though Johnson’s story helped shine a light on the fact that HIV and AIDS could affect heterosexuals, it also exposed the prejudice faced by many HIV-positive people. For example, when Johnson was scheduled to play in the 1992 Olympics, some competitors were warned against playing the American team, for fear of contracting the virus on the court. (By the time the Olympics actually rolled around, however, there was little controversy about his playing.) When Johnson said he might return to the NBA that same year, a TIME/CNN poll revealed that 30% of respondents believed he should stay away, whether out of fear of the virus spreading through in-game contact or fear for Johnson’s own health under such demanding conditions.

Today, as Charlie Sheen makes news, few observers are likely to be surprised that HIV affects a wide range of people or that he describes his medical status as just one turning point in a life that could be otherwise healthy. If anything surprises the world, it may be his statements that he is able to have unprotected sex without transmitting the virus, a testament to the effectiveness of the medicine available today. Johnson and Sheen do share one thing in common, in that both are aware that their celebrity makes them candidates for advocacy.

Of course, Sheen is not the first person to illustrate that medical and societal attitudes toward HIV and AIDS have changed. Magic Johnson himself did it in 1996, when he returned to the NBA.

“In 27 minutes, the Lakers’ old point guard and new power forward scored 19 points, assisted on 10 other baskets and pulled down eight rebounds. As impressive as those numbers were, it was the transcendent smile he flashed throughout the game that made the night so special—not just for the 17,505 who were there, or for the 3 million households that watched the game on TV, but also for the 19 million people around the world who are trying to cope with the fact that they, like Magic, are HIV-positive,” TIME noted. “Says Sean Strub, the founder and publisher of Poz, a bimonthly magazine with a readership of 315,000: ‘This is going to tell tens of thousands of people with AIDS and HIV that they don’t have to give up. They don’t have to believe the death hype. They can go on with their lives.'”

Read the full Magic Johnson cover story from 1996, here in the TIME Vault: As If By Magic

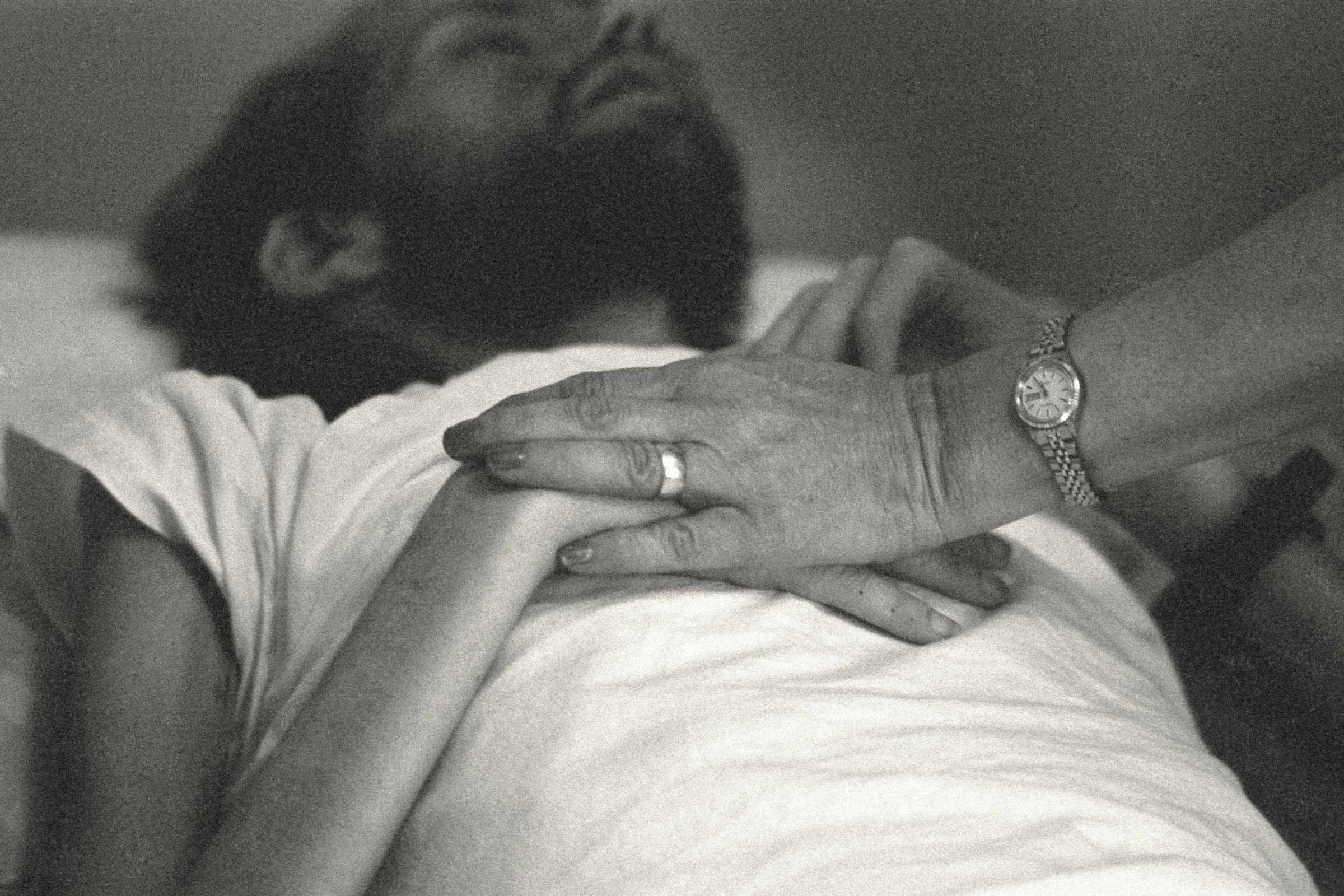

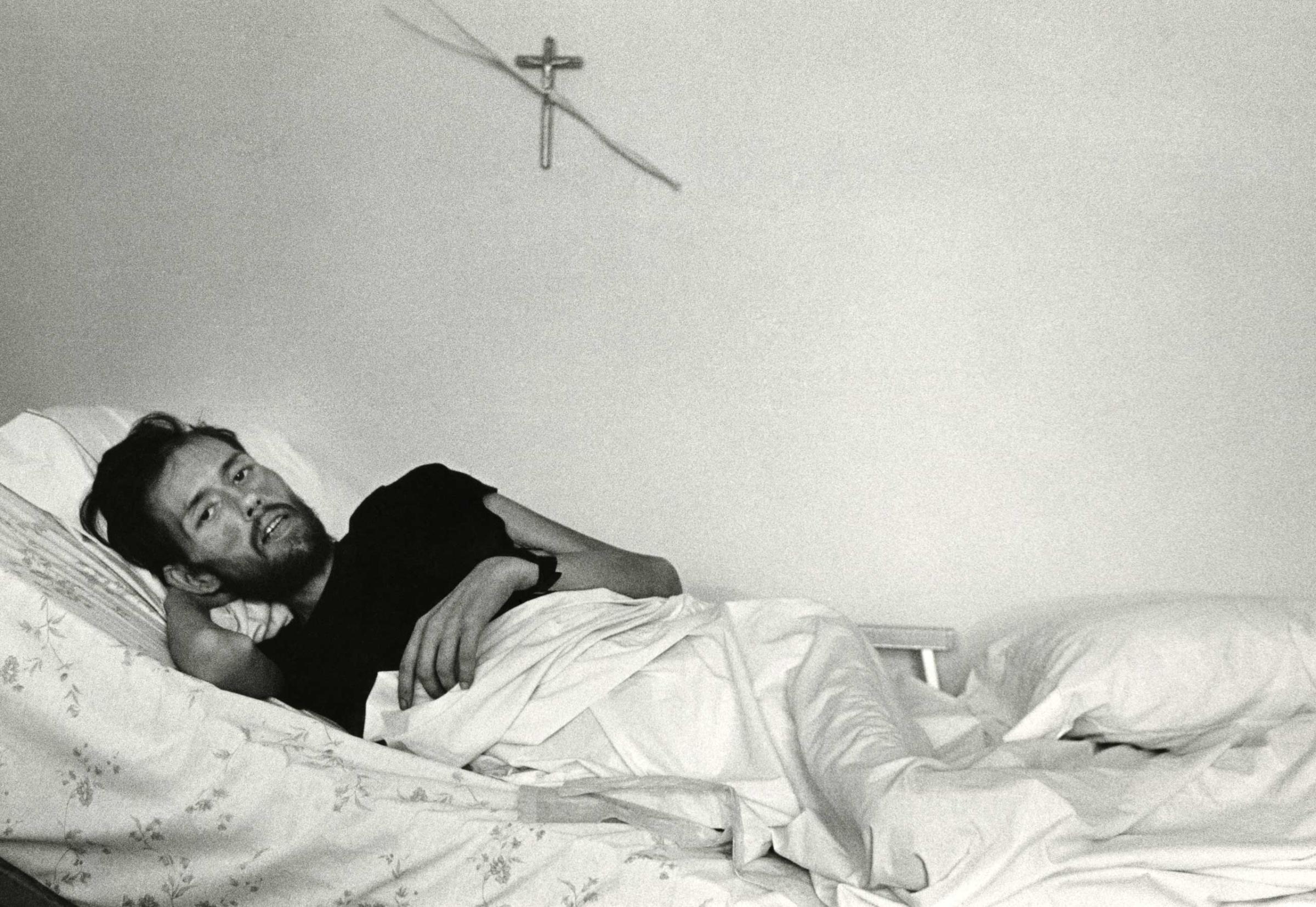

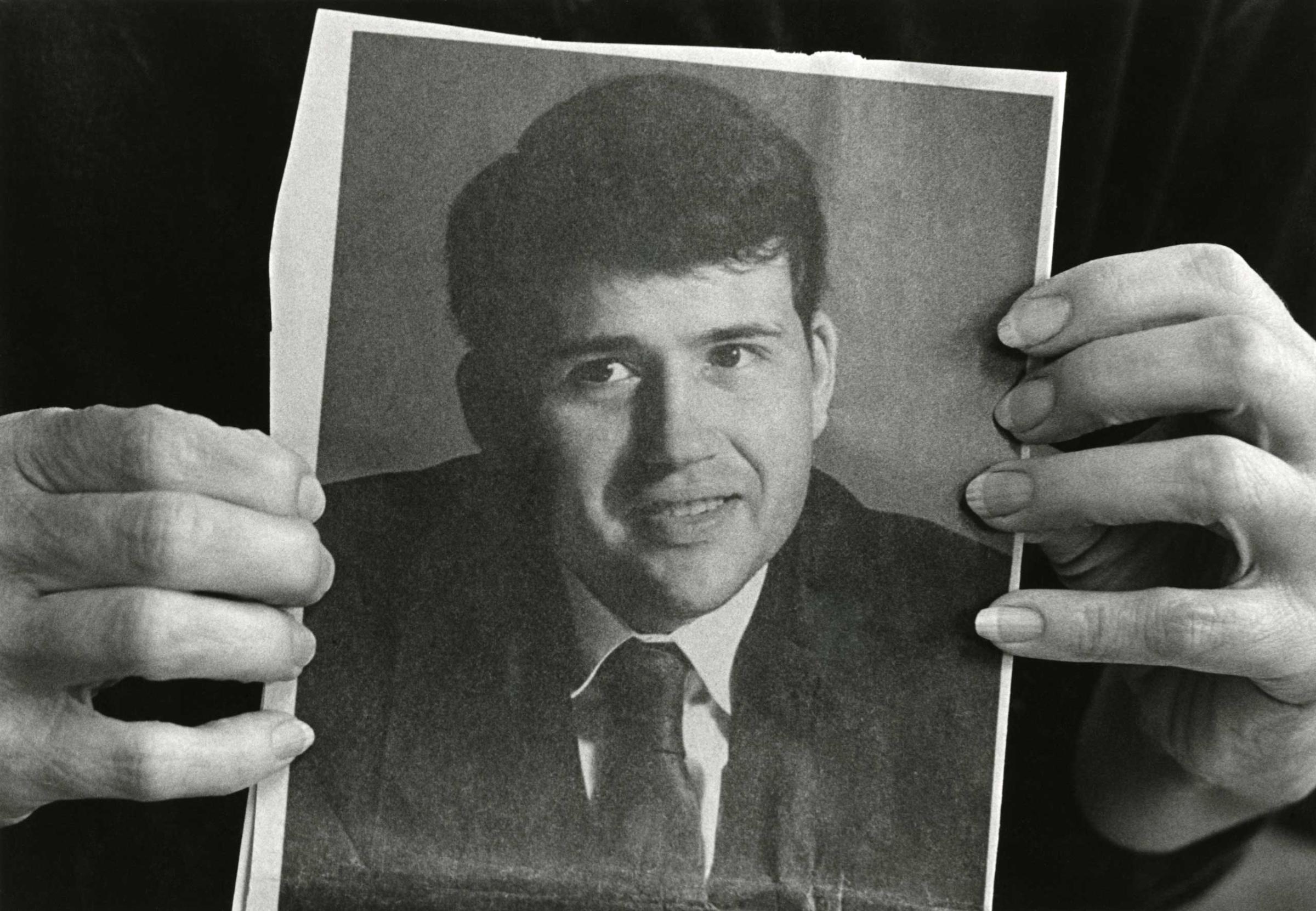

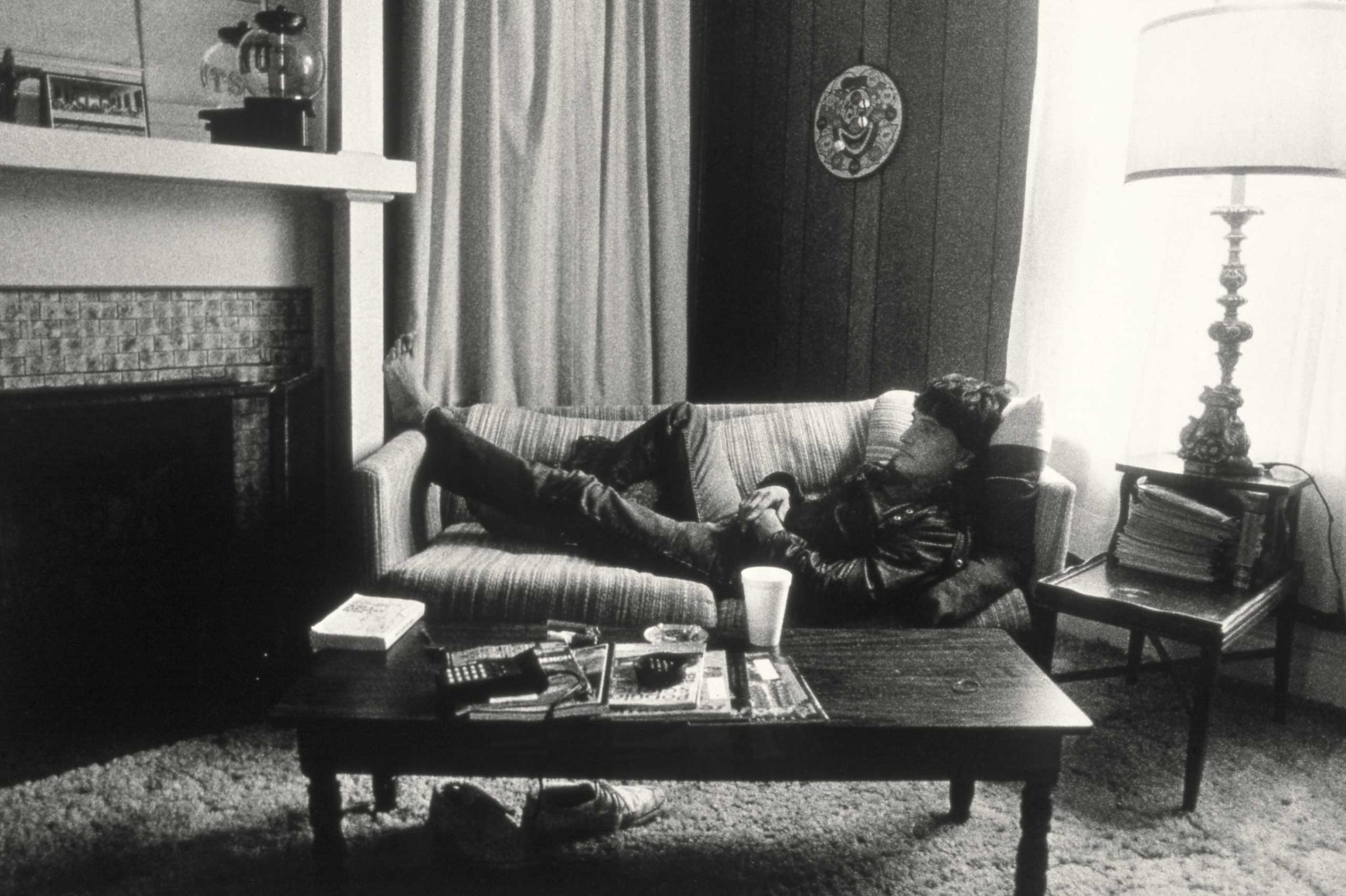

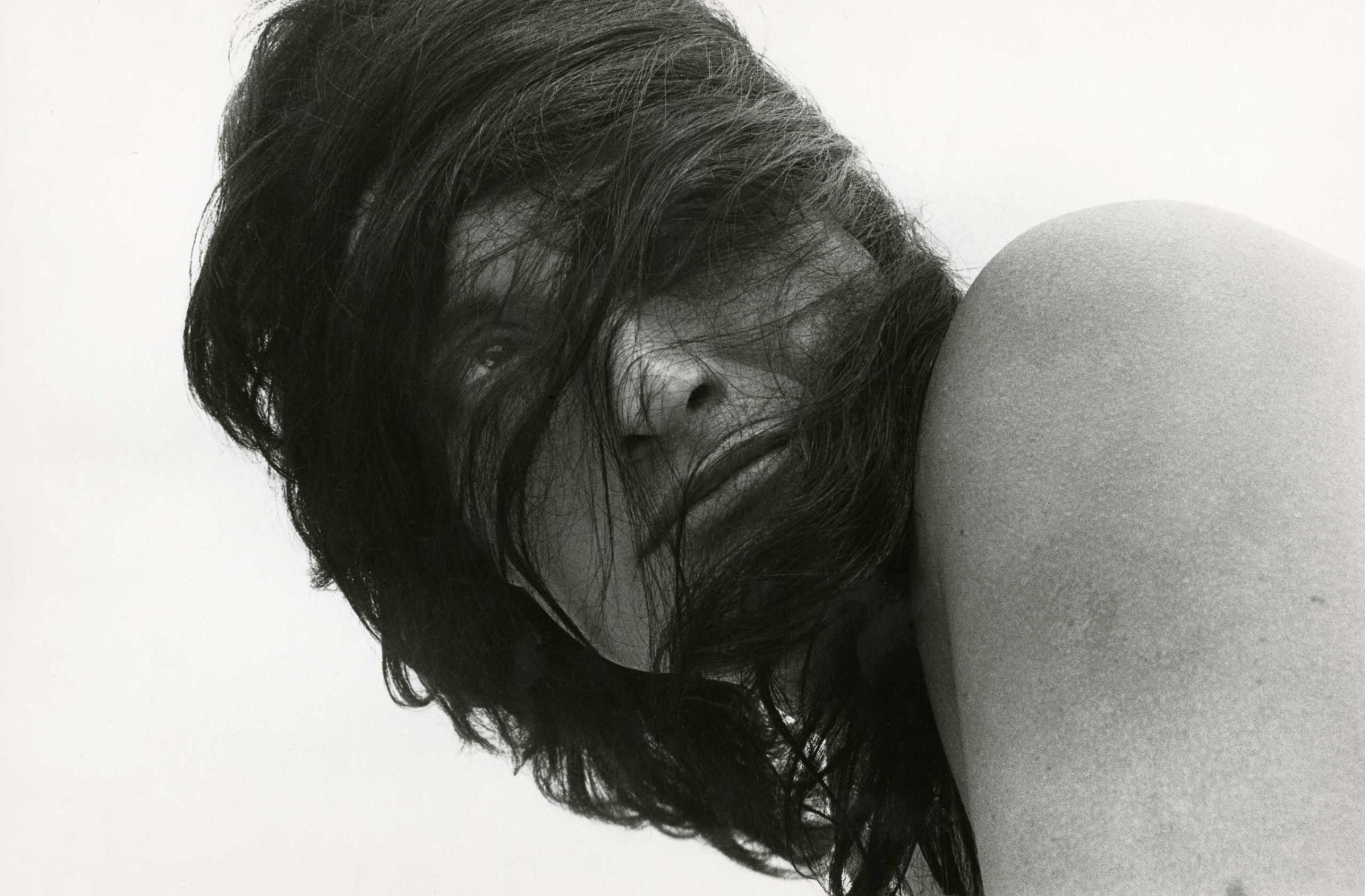

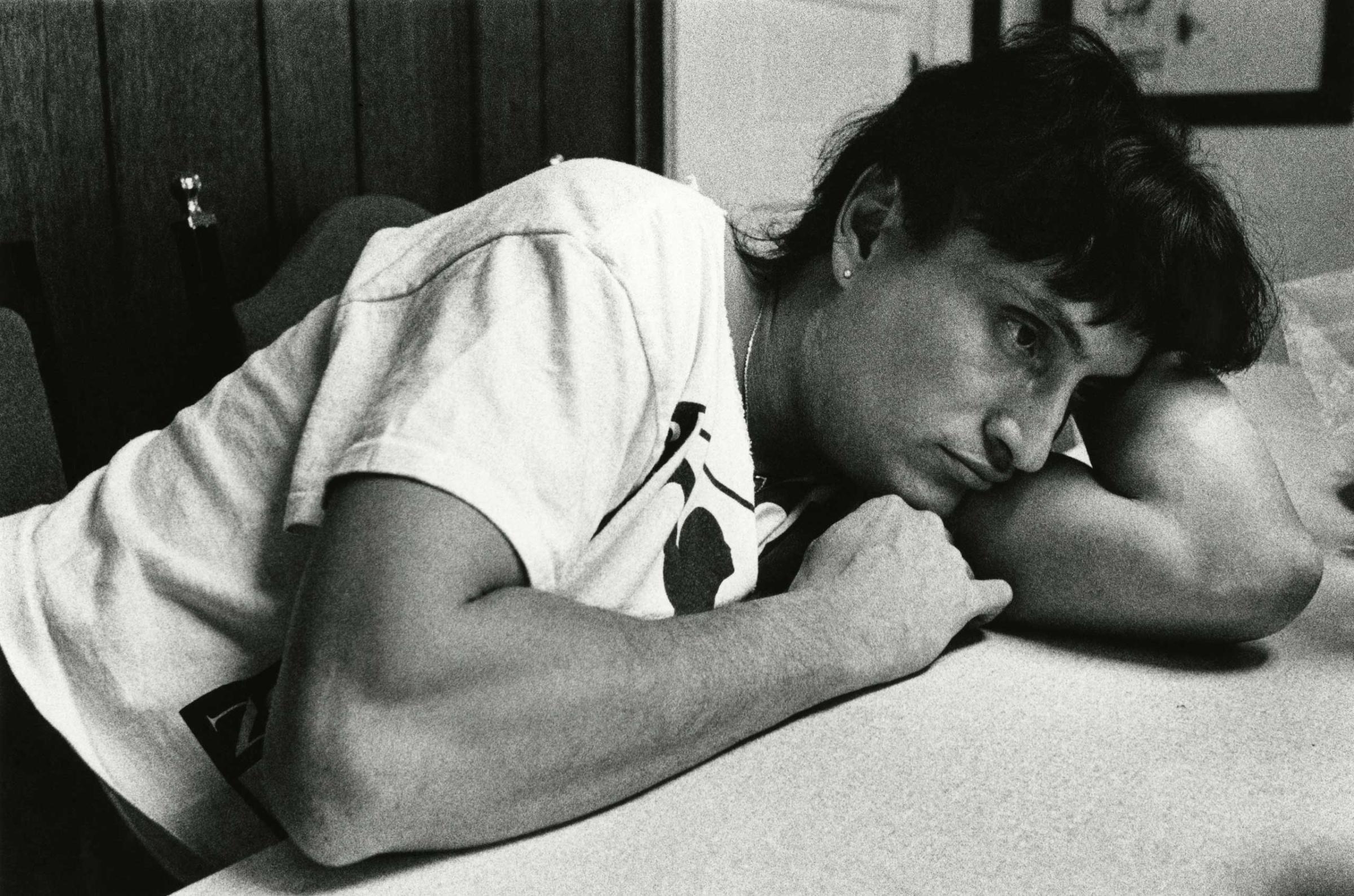

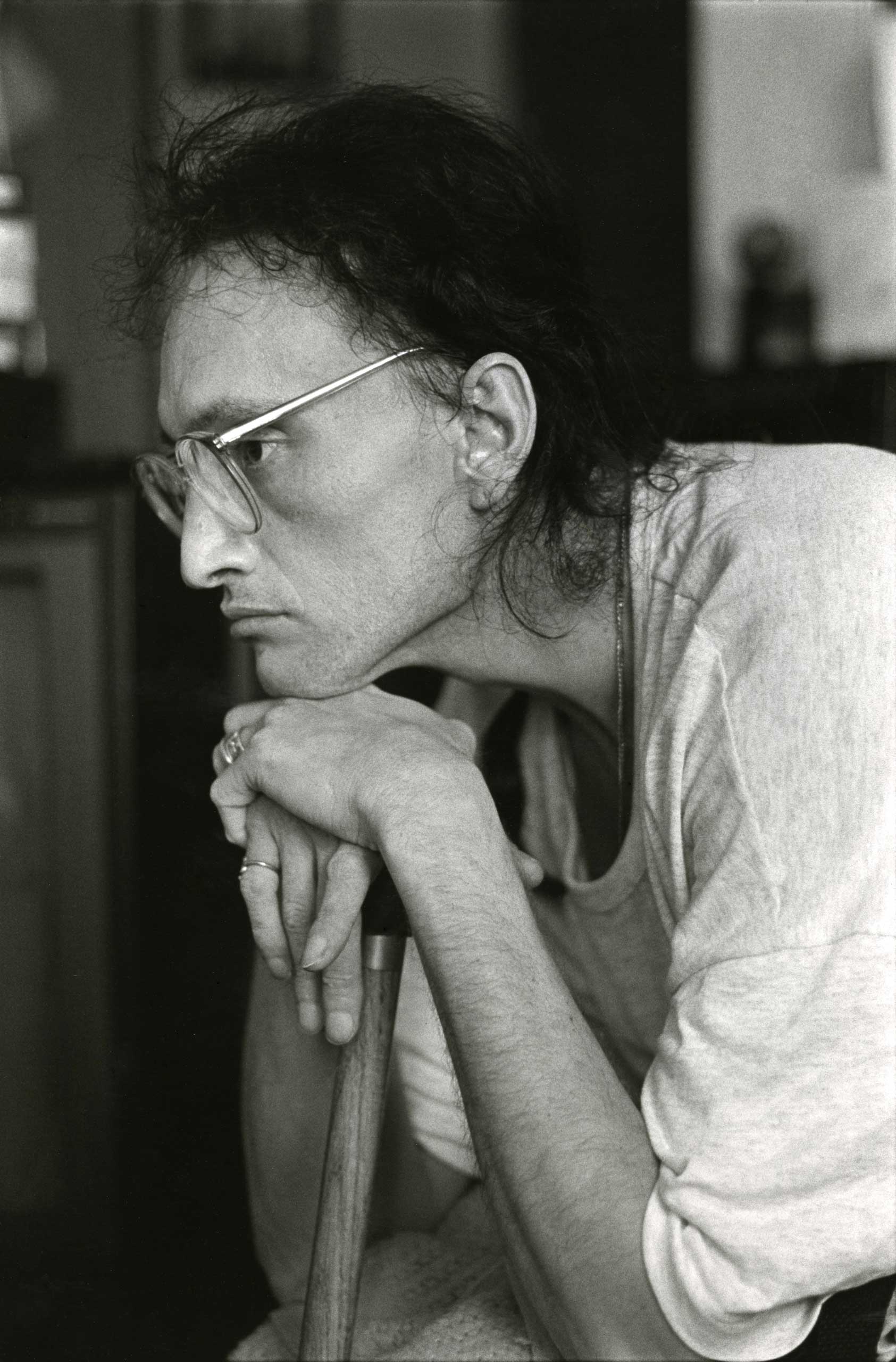

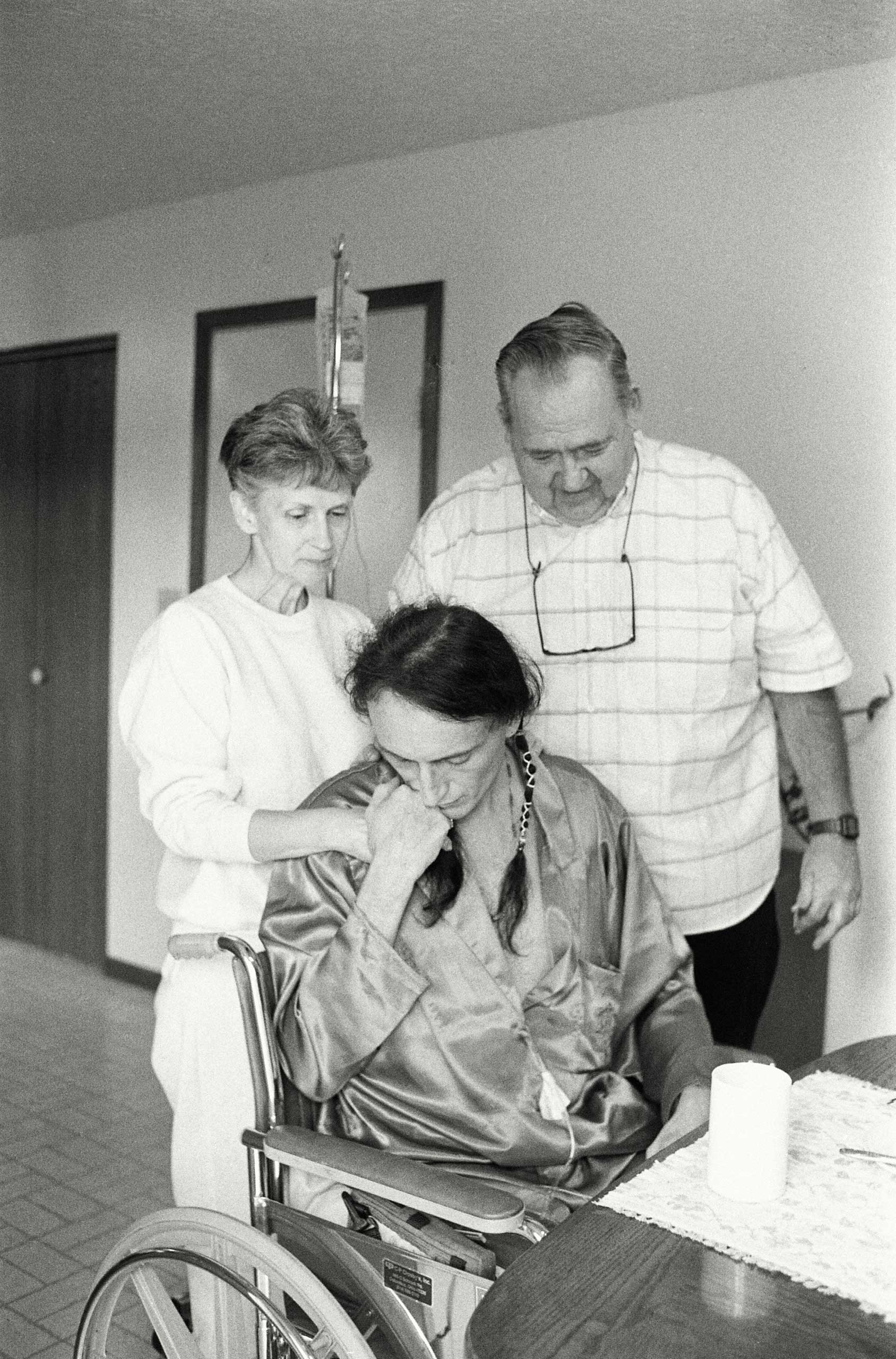

The Photo That Changed the Face of AIDS

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com