In the movie Suffragette, out Oct. 23, a clear-eyed band of working-class British women, frustrated by the failure of peaceful attempts to secure their right to vote, employ militaristic tactics in pursuit of their goal. They set off bombs in public trashcans, hurl rocks through shop windows and set fire to politicians’ homes. These were not, as screenwriter Abi Morgan told TIME in a recent interview alongside director Sarah Gavron, “middle-class ladies in bonnets bashing tambourines.” They were a group of very angry feminists.

The film doesn’t use the phrase “angry feminist,” of course—it wasn’t around in 1913. The association between feminism and anger can be traced to the radical feminism of the 1960s, when that “ism” took on the connotations of bra-burning and man-hating. And those stereotypes still exist today, if less conspicuously, as evidenced by the responses of a bevy of young stars when asked, in recent years, if they identified as feminists. No, said Taylor Swift, Shailene Woodley, Kelly Clarkson and Lady Gaga—some of whom have since reversed their positions—with Clarkson explaining that the word is “too strong” and Woodley and Lady Gaga both protesting, “I love men.”

Ever since Beyoncé embraced feminism in front of millions at the 2014 Video Music Awards, the ideology has enjoyed a more mainstream following, albeit in a friendlier, more populist, generally non-angry form. The question for Suffragette, then—beyond the matter of its efficacy as a conveyor of underappreciated history—is whether a movie about angry feminists a century ago might help bring angry feminism back into vogue today.

Morgan isn’t particularly concerned with the word “anger”—after all, she acknowledges, “the world can make you very angry.” “I think what we have to take the curse out of is the word ‘feminism,’” she continues. “In the same way as [the suffragettes] were undermined and ridiculed in the press and in Westminster, part of the propaganda machine is to subvert that word and make women and men feel very uncomfortable with it.”

One challenge in depicting a movement as remote as the women’s suffrage movement is its potential to feel, at least for some viewers, too far in the past to fully identify with. It’s a challenge Morgan and Gavron thought long and hard about while making the film, and one Gavron addressed in her direction. “We tried to break with the convention of the period drama,” she explains, “to make it feel visceral and follow those women down the street and be in their shoes.”

The filmmakers also posit that despite the near universality of women’s suffrage today (women in Saudi Arabia, text at the movie’s end announces, still cannot vote, although that’s set to change this December), many of the ancillary issues invoked in the film are far from resolved. While researching the period for the script, Morgan found that “the women’s voices sounded so vivid and so contemporary.” The issues they described in interviews and testimonials—“equal pay, appalling working conditions, sexual violence and abuse at work and at home, parental rights, custodial rights, property rights”—are not exactly relics of ancient history.

A few weeks ago, at the film’s premiere at the BFI London Film Festival, two groups of women showed up to prove this point. Members of an anti-domestic violence organization called Sisters Uncut stormed the red carpet chanting, “Dead women can’t vote,” objecting to recent government cuts to domestic violence services. Another group of demonstrators rallied to protest unequal representation of women in Parliament.

Though some directors might have labeled the protests a disturbance to their film’s big night, Gavron felt otherwise. “The protests were actually extraordinary because they were in the spirit of the film,” she says. “The film is connecting with the fact that we still have issues to deal with in the 21st century, globally and in the U.K.”

For a photo-shoot in Time Out London, the movie’s stars, including Meryl Streep and Carey Mulligan, donned shirts emblazoned with suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst’s incendiary quote, “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave.” The shirts, and the suggestion some inferred from them that escaping slavery is a simple choice, incited admonishments for failing to acknowledge the intersectional nature of feminism.

But Morgan, in many ways, welcomed the controversy. “I think if it becomes the narrative of this film, whose intention is so sincere to promote the equality of all women globally, then that would be unfortunate, she says. But barring that, she explained, “I think it’s a really important conversation, I think we have to have it. It’s brilliant it’s been raised, and we have to keep talking about it.”

It may be easier for the average viewer in 2015 to justify the anger of the suffragettes—who were fighting for a right many today take for granted—than it is for some to swallow anger in this age of pop culture embracing feminism. But for Gavron and Morgan, it doesn’t matter so much what it is that inspires people to take action—be it anger, hope or desperation. Suffragette is not in the business of proposing how one should feel, but rather the lengths to which one might go if she wishes to inspire change.

We have a variety of tools at our disposal today—blowing up trashcans may be out of favor, where interrupting a red carpet event is more de rigueur—but Gavron and Morgan, not surprisingly, are here to promote one in particular. “Our intention was to advocate to use your vote, and to remind us all that it was hard-won.” Whether one’s feminism is angry or hopeful, it’s most effective, they insist, when channeled through the tug of a voting booth lever.

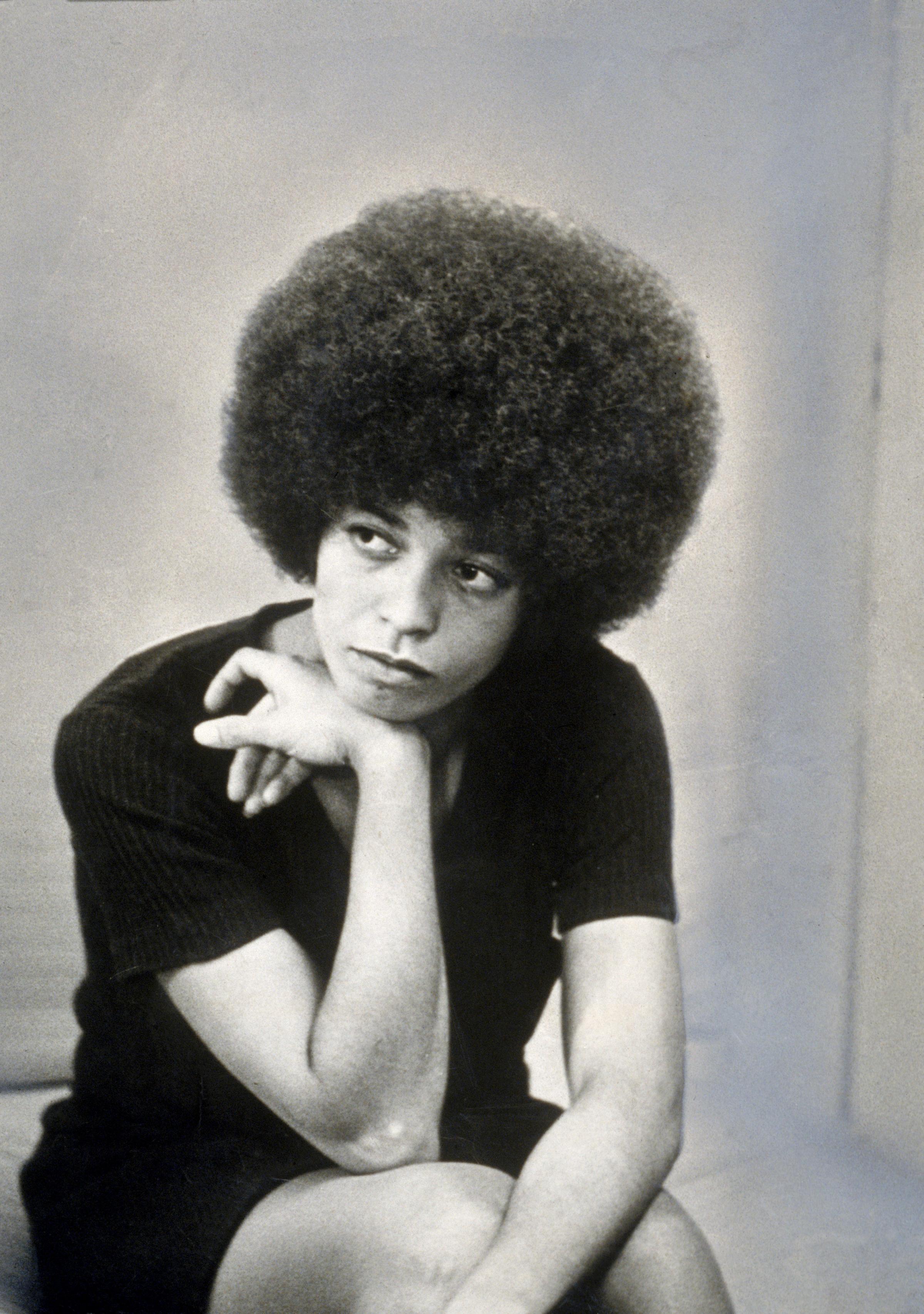

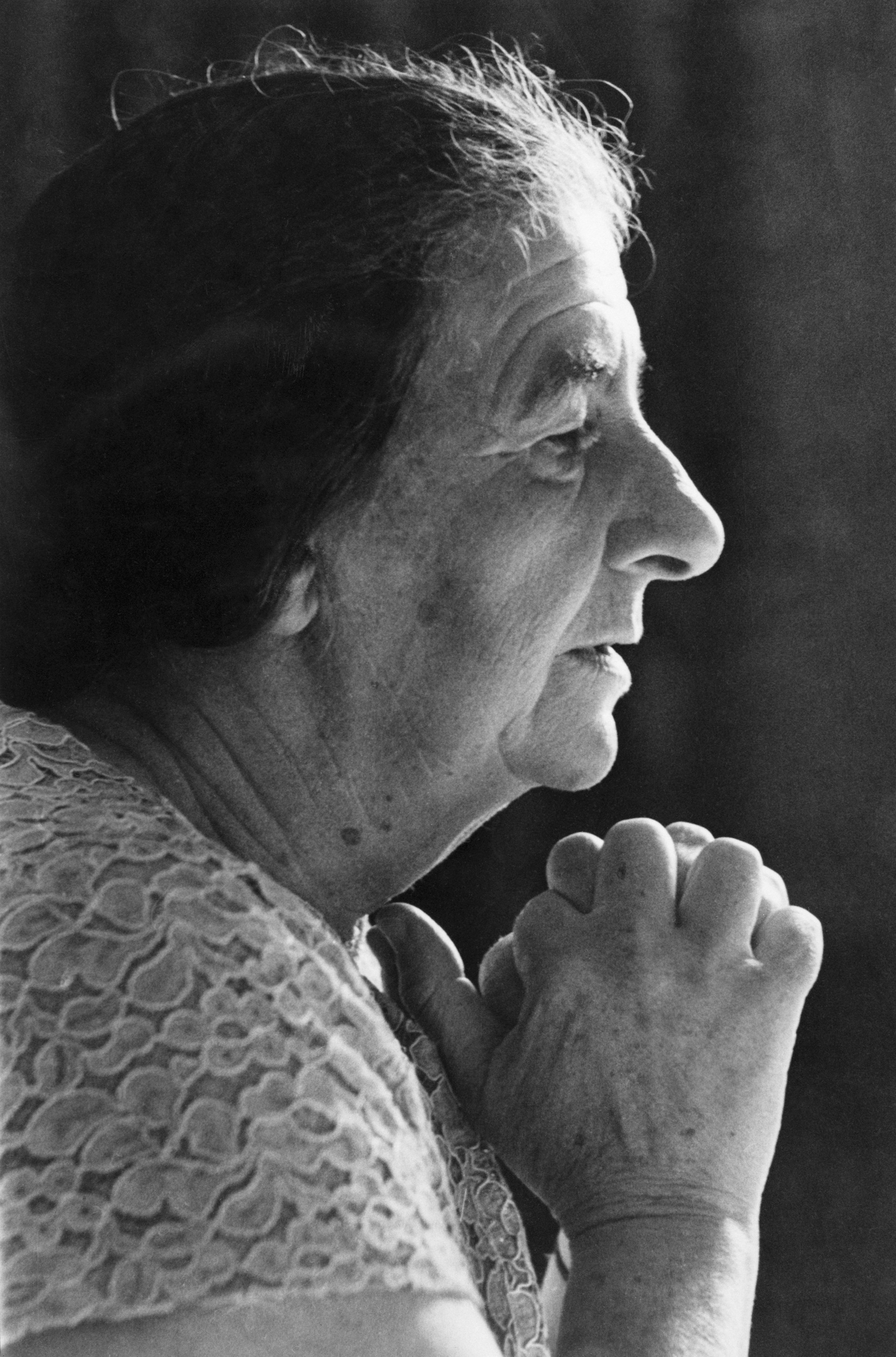

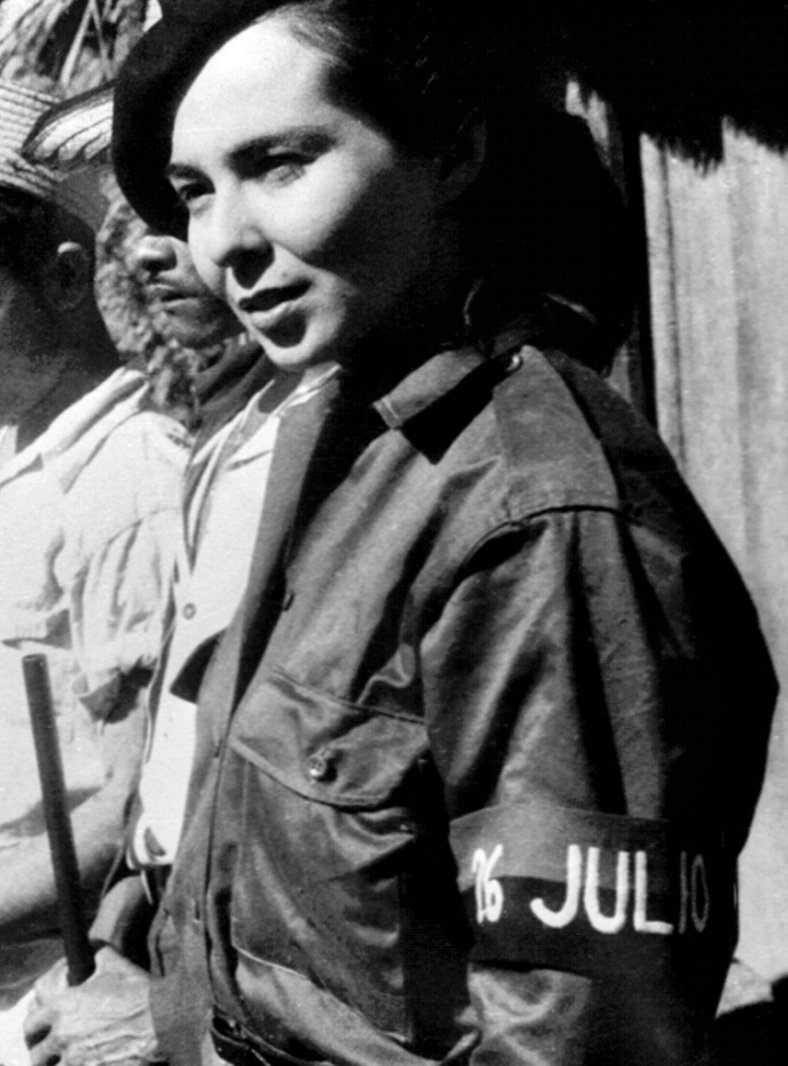

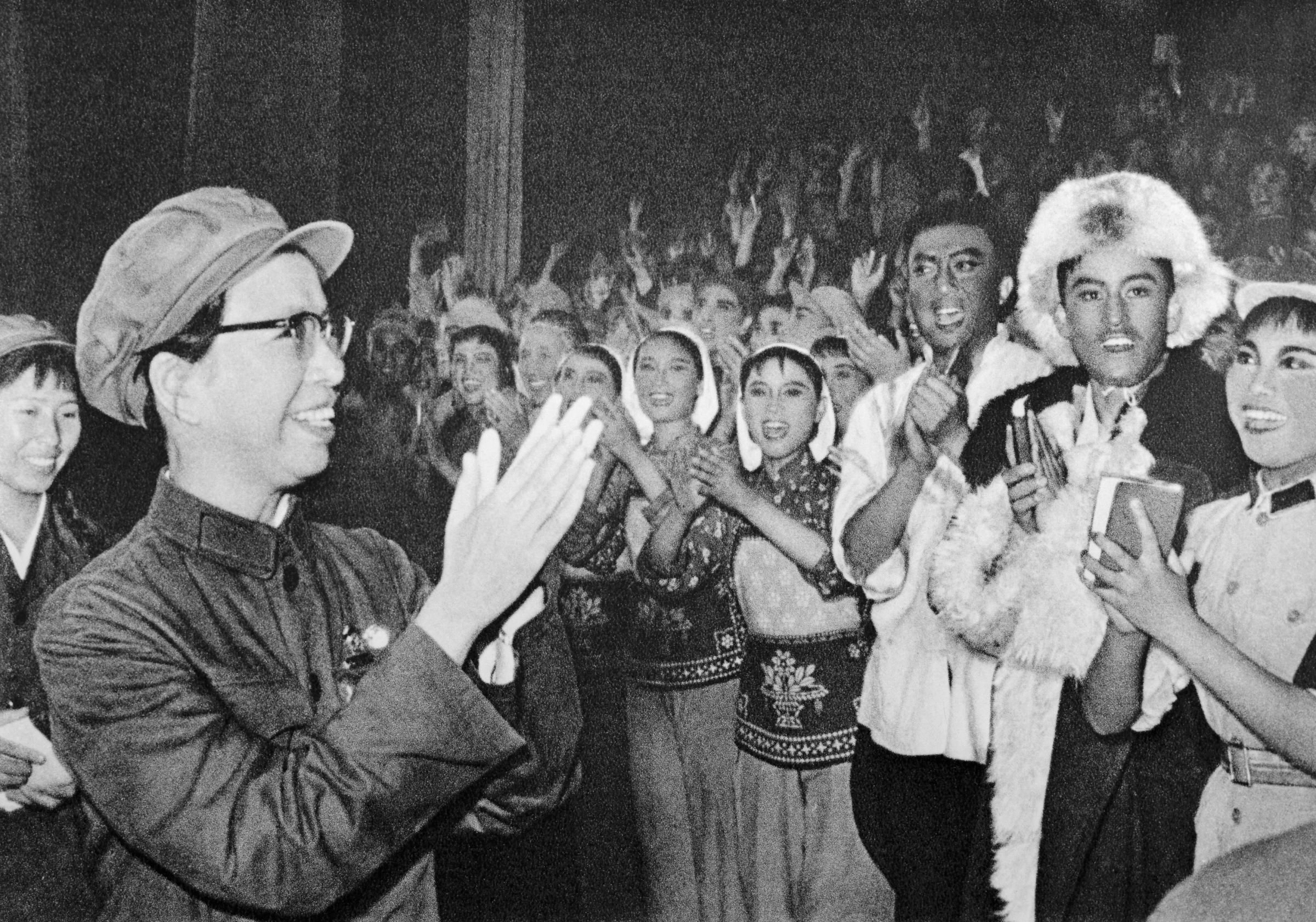

17 of History’s Most Rebellious Women

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com