Without the French language, English speakers wouldn’t have adultery, crime, revenue, virgins, tarts or wardrobes. Students of feminism also wouldn’t have the raucous historical footnote that is the difference between the suffragist and the suffragette, the namesake of a new film starring Meryl Streep, Carey Mulligan and Helena Bonham Carter that hits theaters on Friday.

Though the meaning of the word has broadened, it originally referred to a very specific—and controversial—kind of woman.

The –ette suffix is a string of letters that came across the Channel—where the French still use it to denote that something is diminutive—and got absorbed into British English, before being shipped off to Americans in the New World. Over the centuries –ette has become a marker of things that are short or smaller-than-usual (cigarette = small cigar; roulette = small wheel), feminine and female (jockette = a female jockey; hackette = a female journalist), as well as imitative and inferior (leatherette = imitation leather; poetette = a young or minor poet).

By the time the early 1900s rolled around, -ette was widely known as a suffix that could be plopped onto the end of any word to convey that the thing was wee or womanly. So when newspapermen were tasked with reporting on a militant shift in the women’s movement that bubbled up in Britain circa 1906, away from polite petitions and editorials arguing for the right to vote and toward breaking windows, this suffix was brought off the shelf to mock the new wave of “hysterical” agitators and “violent cranks,” as one contemporary newspaper described them.

“The word was originally used in a denigrating way,” says Katherine Martin, head of U.S. dictionaries for Oxford, combining a patronizing view of femininity and triflingness that is “ultimately condescending.” Historian Nancy Rohr writes this of the term: “The newspaper label implied something not genuine … or even to be ridiculed. The movement was something less than the real thing, as a small kitchen became a kitchenette.” In newspaper articles describing the early days of the more militant movement, the word “suffragette” often appeared in scare quotes, also known as sneer quotes, which suggest that a label is being used ironically or dubiously.

A suffragist could be a man or woman who believed in extending the right to vote, also known as suffrage (which comes from a Latin word for prayers said after a departed soul; the word broadened to refer to a vote cast in favor of someone and eventually the privilege or right voting in general). The word suffragette, however, was used to describe strictly women, the type who were disrupting local meetings and spitting on policemen, the type who were getting arrested and going on hunger strikes in prison and, in one case, taking an axe to a famous Spanish painting of Venus admiring herself in a mirror, which happened to be hanging in London’s National Gallery.

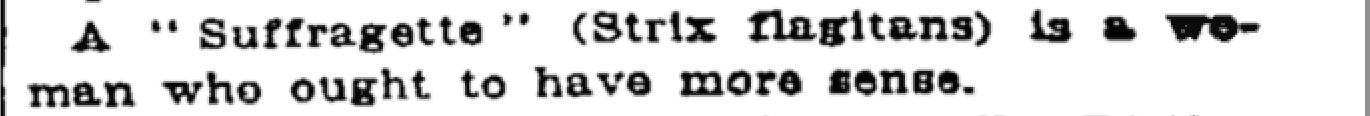

The word was mocked like this in an October 1906 New York Times article containing fake “definitions” from Oxford:

Strix flagitans is Latin that roughly corresponds to “demanding screecher.”

While the women in America continued to prefer the more serious and respected label suffragist, according to an American Heritage guide on usage, many high-profile British advocates, particularly those associated with the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), decided to embrace the term that had caught on so quickly in the press. In fact, the WSPU named their journal The Suffragette and published this note in 1914:

We have all heard of the girl who asked what was the difference between a Suffragist and a Suffragette, as she pronounced it, and the answer made to her that the ‘Suffragist jist wants the vote, while the Suffragette means to get it.’

The word might be used to mock them, and it might have connotations of disapproval, but it was also associated with action, disruption and demanding to be heard no matter the cost. “There’s not actually a lot of daylight between what’s being denigrated and what’s being embraced,” says Oxford’s Martin. “They were being criticized for something they were deliberately doing.” They were not, for instance, storming Parliament by accident.

So instead of ignoring it, many women decided to reclaim a word that their opponents tried to use to insult them, much like the LGBT community has adopted queer, Democrats have embraced Obamacare and women now proudly rap about being bad bitches. Their success is partly evident in the fact that, over time, people have forgotten the controversial connotations of the word, using it to describe any supporter of women’s suffrage in any country. “The word has become much more generalized in memory,” says Martin.

In the past century, the -ette suffix has, meanwhile, gone out of style, just as feminine-marker words like stewardess and even actress have, as preferences have shifted toward gender-neutral labels. Oxford Dictionaries Online notes that today, “new words formed using [the suffix] tend to be restricted to the deliberately flippant or humorous, as, for example, ladette and punkette.”

When World War I broke out, the WSPU also loosened their grip on the suffix, changing the name of their journal from The Suffragette to Britannia, in a show of nationalistic solidarity. British women won their suffrage in 1918, as the war ended. American women followed in 1919, with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

But the actors playing the historical figures in the film Suffragette are still causing a stir with words that shift and change in meaning over time and context. In a Time Out photo shoot promoting the movie, many of the stars donned T-shirts that read “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave,” a quote from a 1913 speech by suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. Some readers took offense at a comparison that they felt minimized the history of actual slavery, particularly in the U.S. The magazine didn’t apologize, but they did release a statement explaining that such a comparison was obviously not their intention. And they did publish Pankhurst’s quote in full, a lecturette worthy of her epithet:

I know that women, once convinced that they are doing what is right, that their rebellion is just, will go on, no matter what the difficulties, no matter what the dangers, so long as there is a woman alive to hold up the flag of rebellion. I would rather be a rebel than a slave.

13 Great American Suffragettes

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com