The first time that Gustavo carried out a hit, he got too close to the victim and the blood exploded all over him. Growing up in a slum of Medellin, Colombia, he had been doing jobs for the cocaine cartel since he was 13, and this assassination, which he did when he was 18, was his graduation to become a sicario – a hit man. An older sicario had mentored him, showing how he had to shoot in the head and heart from a safe distance. But in the heat of the moment, he panicked and sprayed. As a result, he had to throw his bloodied clothes away and he had nightmares of the victim’s guts clinging to him.

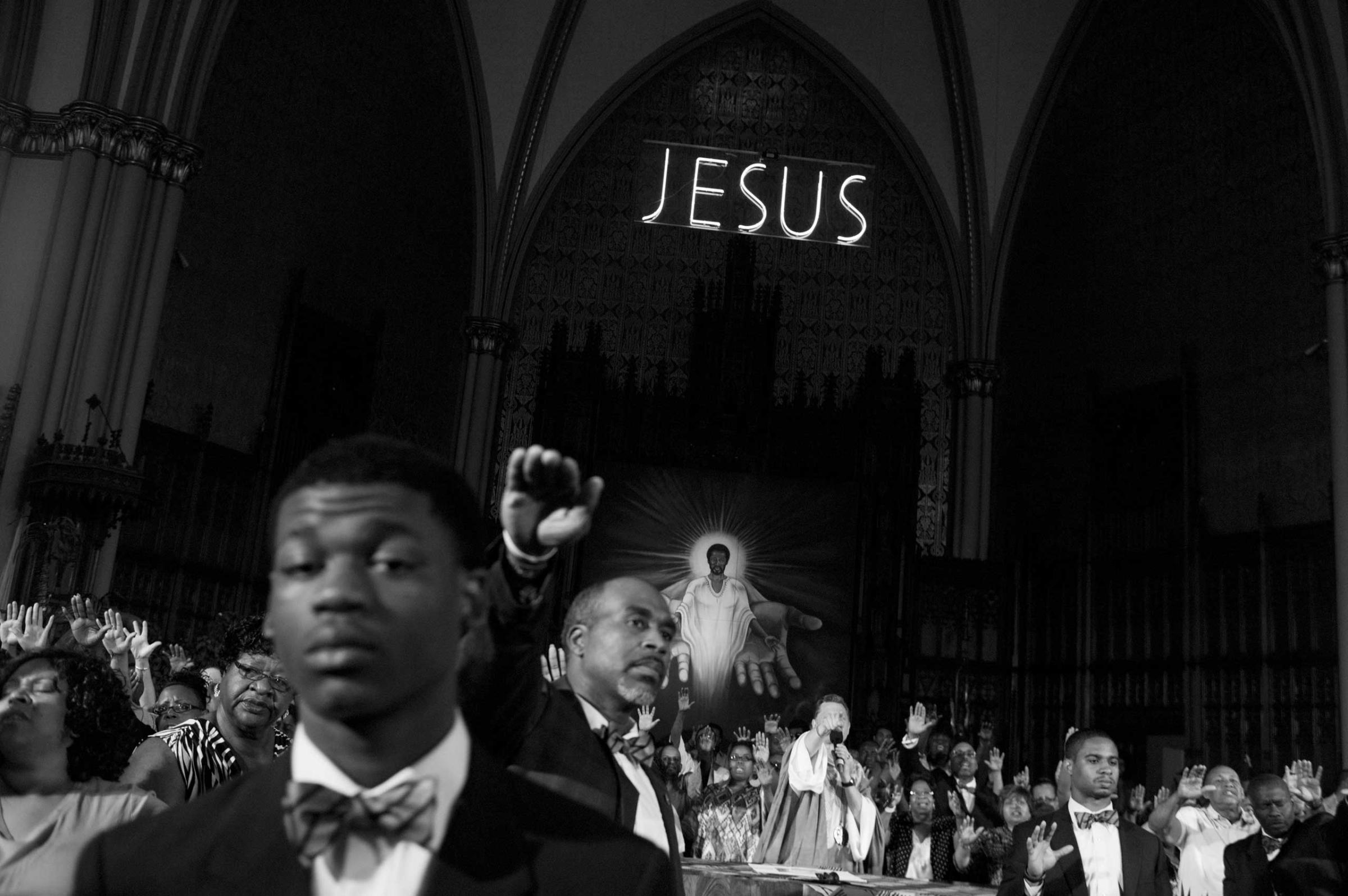

On his second hit, however, Gustavo was calmer, killing with two clean shots and driving away on a motorcycle unscathed. Getting new targets every few weeks, he killed ten, then 15 then 20 people, until he lost count. The bad dreams stopped, and he developed a mindset of not pondering on his victims. “I keep focused and do my work,” said Gustavo, a bone thin youth with a crew cut, dressed in a trendy green shirt and Hawaiian shorts. “Before I go out, I pray to Jesus and clear my mind. I never take drugs or drink before a job as I need my five senses. When I come back, I will relax and smoke a spliff and listen to music.”

I interviewed Gustavo in a safe house in Medellin, Colombia for a 2011 book, “El Narco,” along with photographer Oliver Schmieg, who had made the connections into the cartel. I was trying to understand the wave of bloodshed that made Latin America the most murderous region on the planet, and the testimonies of active sicarios was a big piece of the puzzle. In the years since his chilling interview, I have talked to more sicarios in Mexico, Honduras and Ecuador. I also interviewed similar paid assassins in Jamaica, who call themselves shottas, and in Brazil, who call themselves “soldiers,” and work for trafficking “commandos.”

Their stories paint a troubling picture of how armies of killers linked to drug cartels have grown across the Americas, driving the sky high murder rates and overwhelming security forces. While homicides have fallen in most of the world since 2000, they have risen in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the United Nations. A report this year found 43 of the world’s 50 most violent cities are in the region. The total death toll is staggering. Between 2000 and 2010, there were more than a million murders there, according to the U.N. While various factors drives this bloodshed, organized crime has a big presence in all the countries with the worst violence.

The word sicario was first used in Colombia in the 1980s, but was taken up in countries such as Mexico and Honduras as the cartels carved out new smuggling routes amid the war on drugs. Narco terms also spread through soap operas and songs from both Mexico and Colombia. With the release of the movie Sicario in American theaters last week, the word is finally working its way into English.

The Colombian traffickers formed the first sicario squads to protect the billions of dollars they made trafficking cocaine to the United States amid the 1980s boom in the white gold. In his book, “The Horseman of Cocaine,” journalist Fabio Castillo reports that the architect of the “most violent machine of death the country has ever known” was a cartel operative called Isaac Guttnan Esternbergef. Traditional assassins in Latin America had been well paid professionals who killed silently, but Guttnan saw that young men from the slums could be recruited en masse, drawn to a wage and a sense of purpose. They took their name from the Latin sicarri – which described Zealots in Judea who assassinated Romans with daggers.

Gustavo is typical of these sicarios, the son of a laborer from a tin-roofed house on Medellin’s slopes. Being a killer earned him a salary of $600 a month plus bonuses of $2,000 to $4,000 for hits, more than his father could ever make shifting cement. “Some people murder because they get pleasure out of it, because they actually enjoy killing and get addicted to the blood. But I do it out of need,” he said.

He felt less guilt about his bloodshed by seeing himself as simply obeying orders. “I get a call saying, ‘There goes the little girl (code for the victim). Take care of her.’ They will give me a photo of the target. And then we will go and hunt.” Sicarios across the region kill inside a command structure rather than out of individual anger, driving the machine of murder.

As Mexican cartels moved increasing amounts of cocaine, crystal meth and heroin over the U.S. border in the 2000s, they expanded their own armies of sicarios. Many were also ghetto youth but others were former soldiers or police officers. In a prison in Ciudad Juarez (where part of the film Sicario is set), I interviewed Gonzalo, a former police officer who became a head of a squad of sicarios in the city. He described how they were so effective at killing because they planned hits like operations and had a broad network of spies.

“We have all the points covered. We work like the police in the United States, you understand? In every job, we have points (operatives). If someone tries to get away, there will be a point that will respond,” he said. “A lot of women move in this environment as well as kids, 16 to 18 years old. They can be very important points, watching things.”

As cartel violence rages on through the 2010’s, sicarios have also taken to social media to show off their power over life and death. Groups of hit men with names such as “The Anthrax” release videos where they pose in masks and body armor holding high-powered weapons. Such displays gain millions of hits but they can also expose the killers. Twitter photos of Anthrax boss José Rodrigo Aréchiga were reported to help lead to his arrest in Mexico before he was extradited to the United States and pleaded guilty in a San Diego court in May.

Despite many sicarios ending up in prison or tombs, there appears to be no shortage of new recruits. Many young men, or often teenagers, join up, as well as some women. This flood of killers has pushed the blood wages down in places. In February, I interviewed a killer in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, who called himself Montana after Al Pacino’s character in the movie Scarface. He carried out his first paid hit when he was just 14, shooting a drug dealer who failed to give a cut to the local gang. He was paid 1,000 lempiras or about $45. “I felt excellent,” he said. “You get addicted to killing. You want to kill again just to get that buzz.”

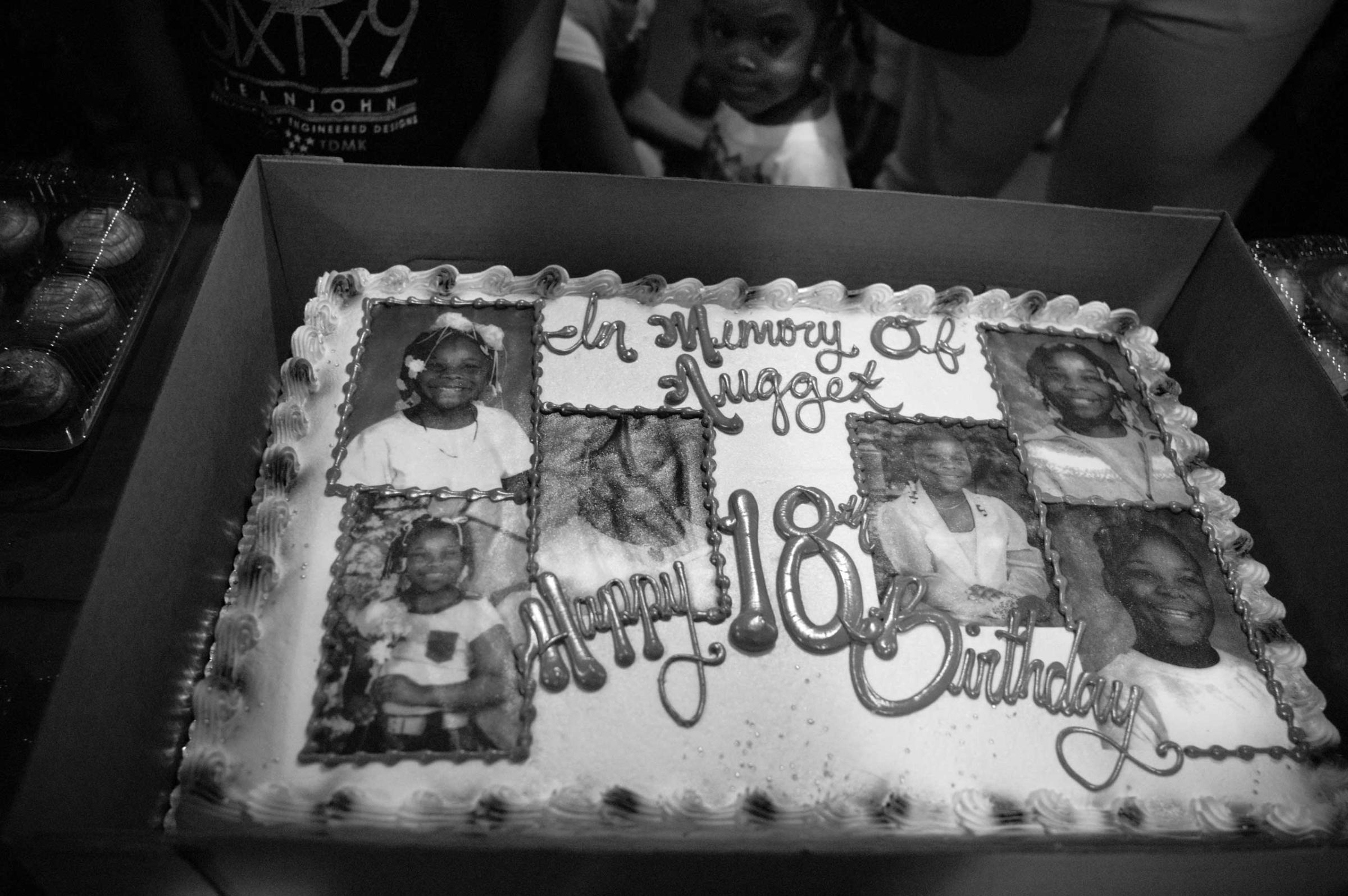

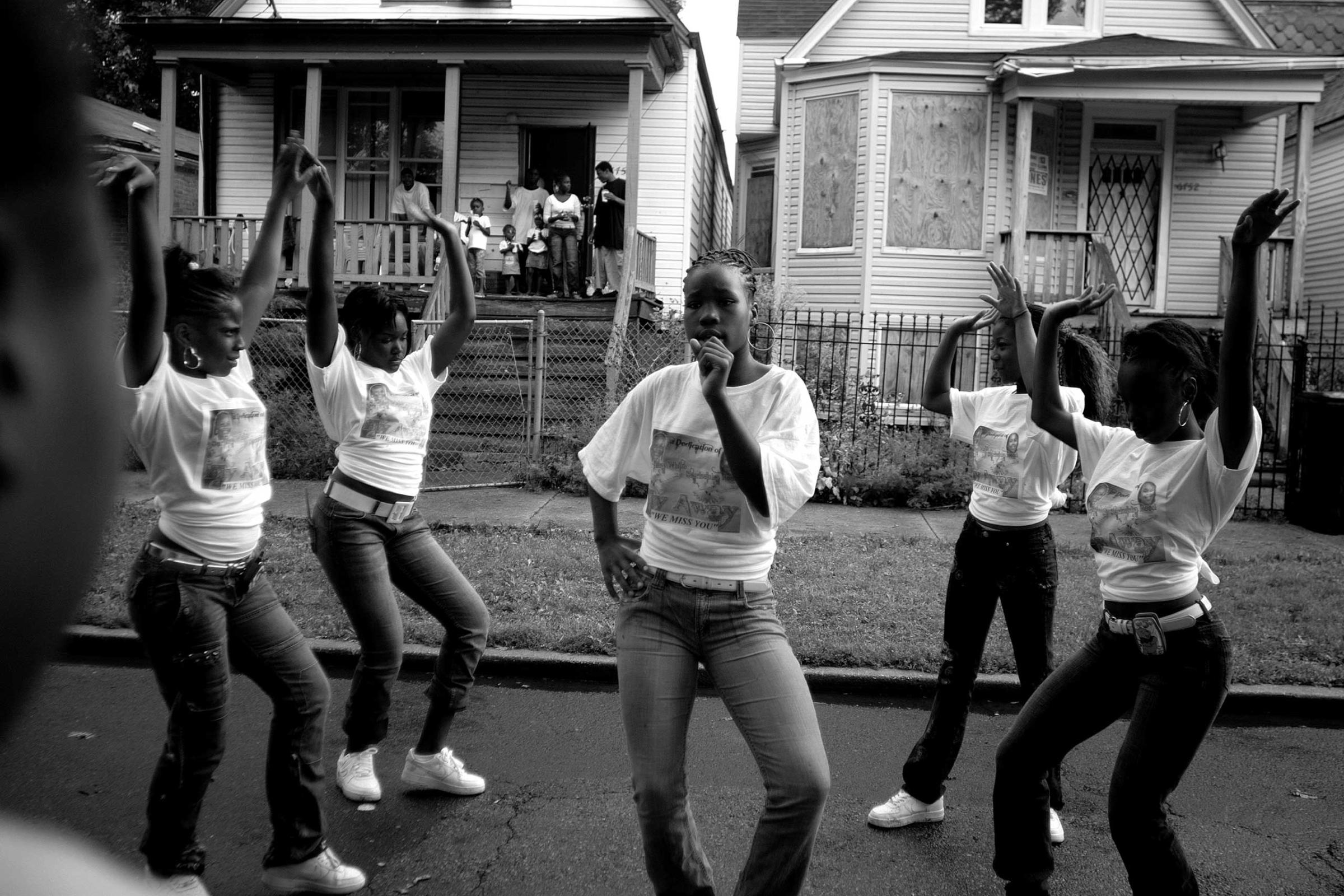

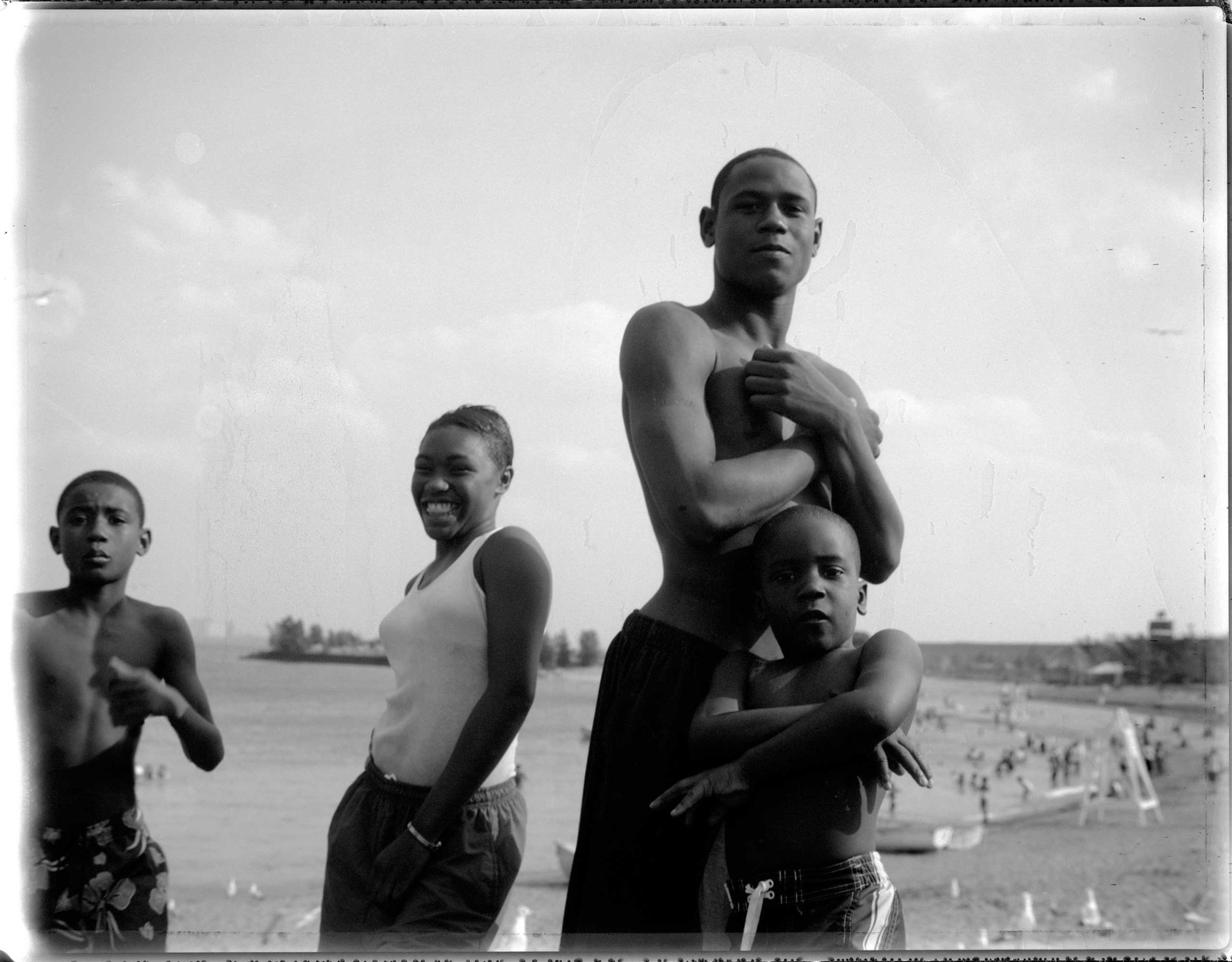

Go Inside the Lives of Families Affected by Gun Violence

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com