On Oct. 13, the Democratic candidates for President will meet for their first debate, and billionaire conservative industrialist Charles Koch will release a new book. Strangely enough, the lefty debaters and the Republican donor will likely give similar answers, when asked, on the matter of what’s ailing the criminal-justice system.

In the past year, eminences from both parties have rushed to condemn this monolith. In July, President Obama became the first-ever sitting President to visit a U.S. prison, after Hillary Clinton gave a major criminal-justice speech in April. On the right, and somewhat more improbably, presidential candidates from Chris Christie to Jeb Bush have spoken of reducing punishments for drug offenders. (Rand Paul has long led this charge.) And then there are the Kochs, Charles and his brother David, who have made the issue a plank in their platform. “It’s created some unlikely bedfellows,” Obama said earlier this year.

Into this curious consensus arrives Michael Javen Fortner, an assistant professor at the School of Professional Studies at the City University of New York, whose new book, Black Silent Majority, attempts to rewrite some of the assumptions at the heart of all this agreement.

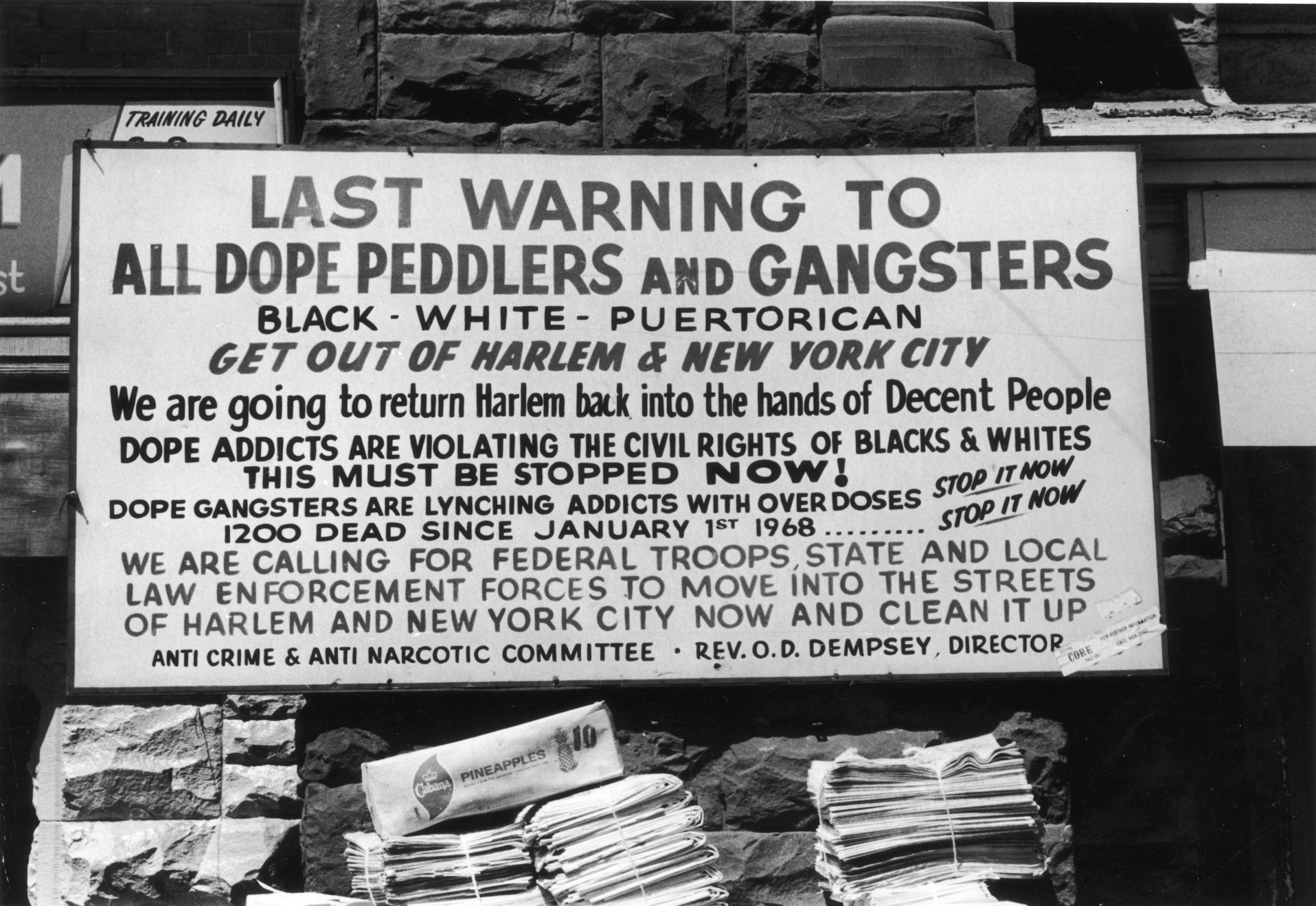

Fortner has a compelling personal story; he grew up in Brownsville, Brooklyn, where one brother of his was stabbed to death and another was incarcerated. His book is an academic history. With postwar Harlem as his focus, Fortner sets out to prove that New York State’s Rockefeller drug laws (responsible for so much black incarceration since their passage in 1973, thanks to the adoption of similar and eventually tougher statutes nationwide) were not simply dreamed up and forced through by cynical white politicians desiring to appear tough on crime. He locates instead a black middle class–aspirational and ascendant despite being trapped in Harlem by racist housing policies–which with the best of intentions used its political clout to attempt to drive drugs out and users and pushers to jail.

The drug on offer in Black Silent Majority’s Harlem is heroin, which brings with it a nasty epidemic. By the late 1960s, the state-funded treatment hospitals overflow, and the neighborhood streets turn dangerous and foreboding. A 1969 paper by the Manhattan NAACP discusses a “reign of criminal terror” in Harlem, and in 1973 a poll finds that nearly 75% of the city’s black and Puerto Rican population favors life sentences for drug dealers. While the offenders in question shared a skin color (and all that has historically entailed in the U.S.) with their neighbors, those citizens were no less inclined toward punishment than white politicians like Nelson Rockefeller. Hence an unlikely alliance of 40 years ago behind a policy that would one day sprawl enough to occasion today’s aforementioned unlikely alliance against it.

Critics have charged that Fortner errs in misidentifying a distinct political class–that his titular silent majority is a group full of hope and fear, yes, but also one skeptical of the police and without much meaningful electoral power. Yet even the reader who questions the strength of his claims would concede that existing narratives have had little to say about black anticrime efforts, even when in 2014 a black American was 27% likelier than his fellow citizens to be a victim of a violent crime.

As the cries for reform grow louder, Fortner’s book aims to complicate the way we think about policing and the penal system. It does so in ways both intended and not. Fortner says he means only to reinsert the wishes of crime victims, and the agency of the black middle class, into the conversation. And he does, with the goal that these groups’ present-day heirs will have a voice in the coming planning of reform.

Yet this provocative history also alerts a rising generation of would-be reformers–the young masses that have recently filled the streets of New York and other cities to protest after each new tragedy–to how a well-intentioned proposal can lead to something unintended and disastrous, like mass incarceration. This lesson should resound, given the political clout the criminal-justice-reform movement continues to acquire. Five decades later, they face a mirror image of the ’60s problem. A solution may be just as elusive.

For more on these ideas, visit time.com/theview

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jack Dickey at jack.dickey@time.com