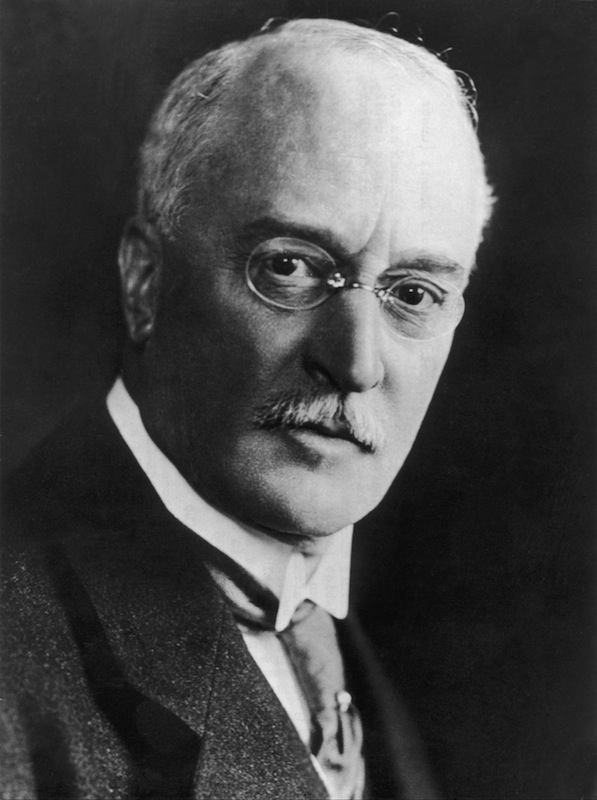

The engine that bears his name earned him a fortune in royalties, and the German engineer and inventor Rudolf Diesel was apparently doing well when he boarded a steamship from Belgium to England on this day, Sept. 29, in 1913. But he never got off the ship the following day. When it docked in England, Diesel simply wasn’t on board.

The circumstances of his disappearance were mysterious, to say the least. The bed in Diesel’s cabin hadn’t been slept in, although “his night attire was laid out on it,” according to the New York Times. Friends and relatives were flummoxed. They speculated that he had fallen overboard, arguing that his frequent insomnia might have made him pace the deck when everyone else was asleep. But the sea had been calm that night, and as the story developed, a more likely explanation emerged: suicide, motivated in part by financial troubles.

The New York Times’ headlines chronicle a strange story that grew stranger every day, starting with “Dr. Diesel Vanishes From a Steamship”(Oct. 1), then “NO RAY OF LIGHT ON DIESEL MYSTERY: German Inventor Was a Millionaire and His Home Was Happy”(Oct. 2), followed by “DIESEL FAMILY IN STRAITS: Missing Inventor Said to Have Left Them in Extreme Need”(Oct. 13) and then “DIESEL WAS BANKRUPT: He Owed $375,000 — Tangible Assets Only About $10,000”(Oct. 15).

By the following spring, an even stranger headline cropped up: “REPORTS DR. DIESEL LIVING IN CANADA: Munich Journal Hears Inventor, Supposedly Drowned, Has Begun Life Anew.” This report doesn’t seem to have held water, however; no follow-up stories could confirm the account.

As TIME told it, in a 1940 story, Diesel had long been plagued by health woes and money troubles — he was a better inventor than investor. But, the story questions suicide as an explanation for his disappearance, arguing that “in 1913 things were going fairly well.” And, it notes ominously, “[n]o note, no clue, no trace of his body was ever found.” (This last point is also up for debate: a body turned up 11 days later, at the mouth of a Dutch river, matching Diesel’s description in appearance and dress, but public opinion was mixed on whether this was sufficient proof of his death.)

Of course, conspiracy theories abounded. One was that Diesel was snuffed out by the German secret service because the Diesel engine played an instrumental part in the development of the U-boat — and they didn’t want him to share its secrets with the Brits. Others suspected rival inventors or business competitors.

While there was never an official investigation into Diesel’s disappearance, its strangeness and his relative celebrity kept the case in the public eye, and a few tantalizing details eventually emerged. One, according to Greg Pahl, the author of Biodiesel: Growing a New Energy Economy, was that just before he left, Diesel gave his wife a bag he told her not to open until the following week. It contained 20,000 German marks, along with financial statements that revealed the depths of the family’s debt.

An even more persuasive piece of evidence was found in his notebook — where he had penciled a small cross next to the date Sept. 29.

Read more about Diesel, here in the TIME archives: His Name is an Engine

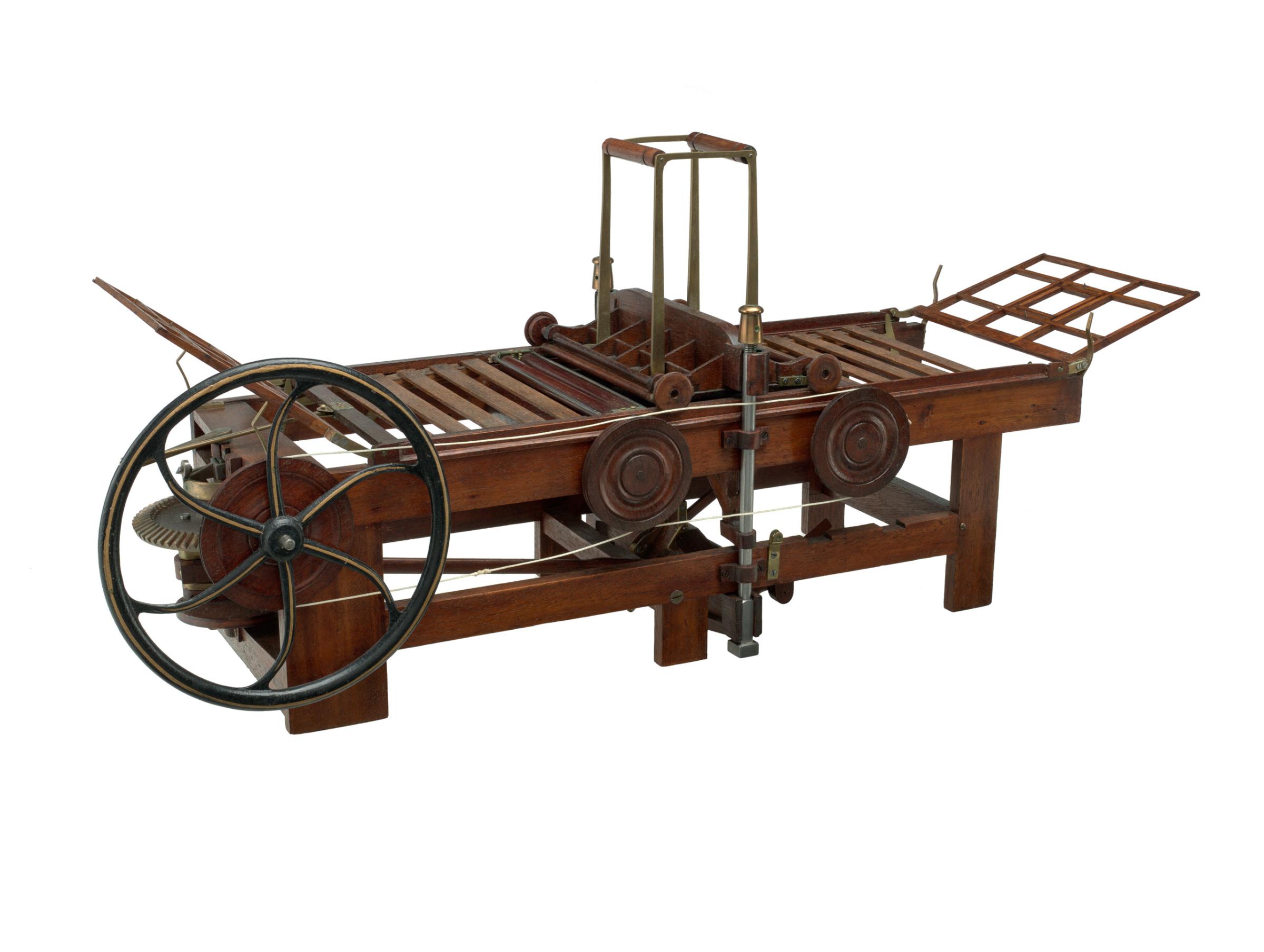

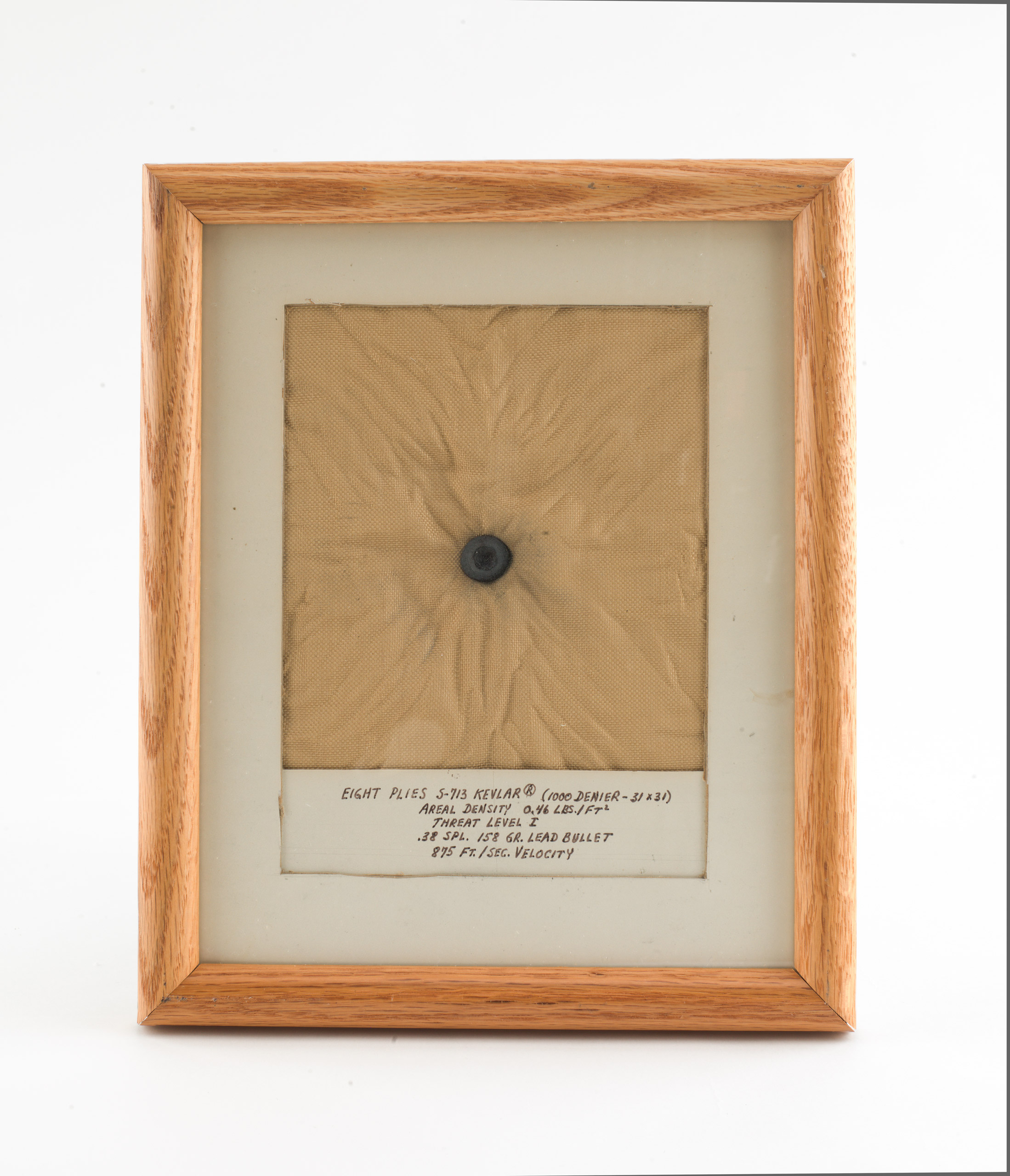

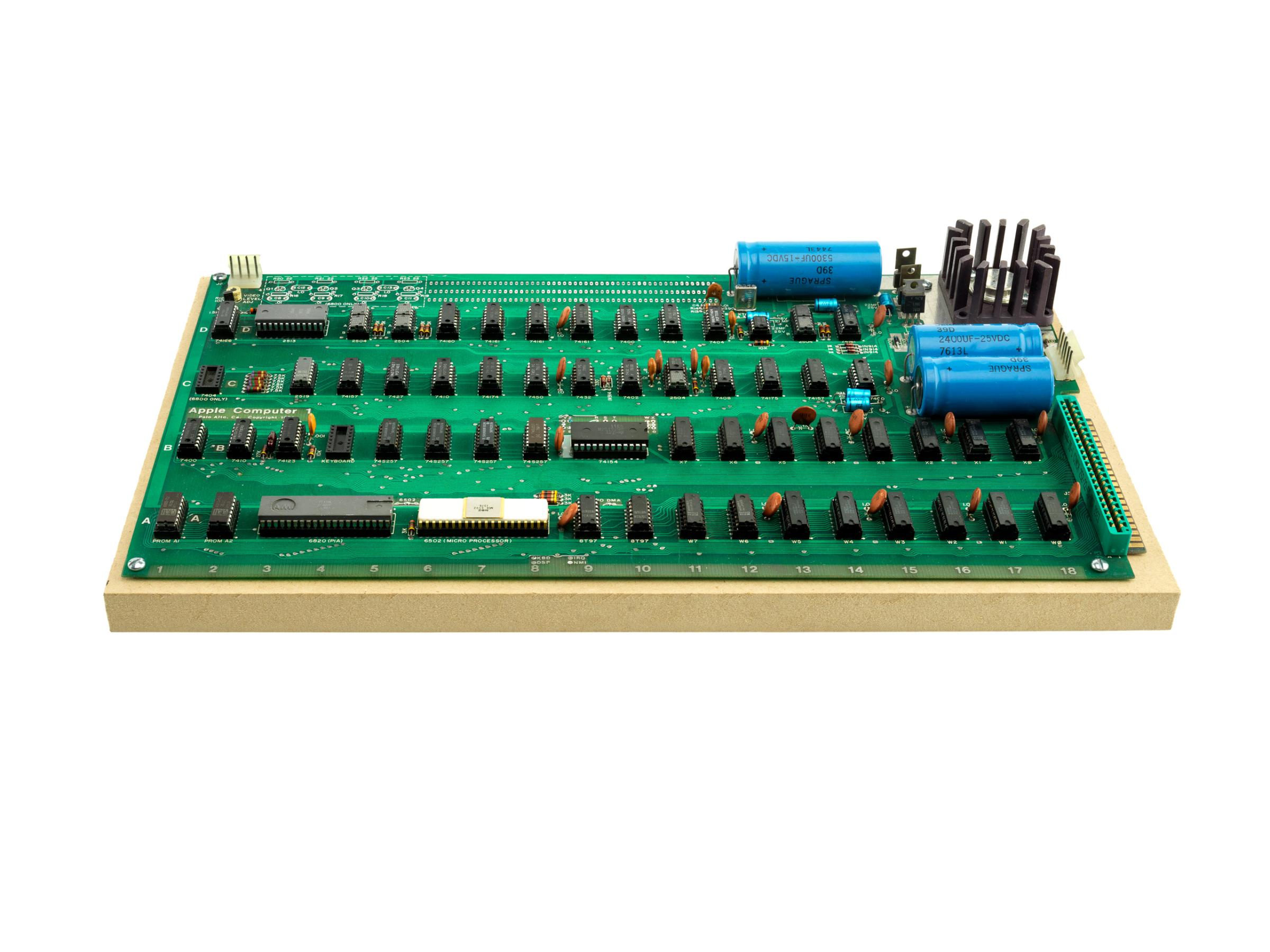

See Original Models of the Apple I and Other Iconic American Inventions

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com