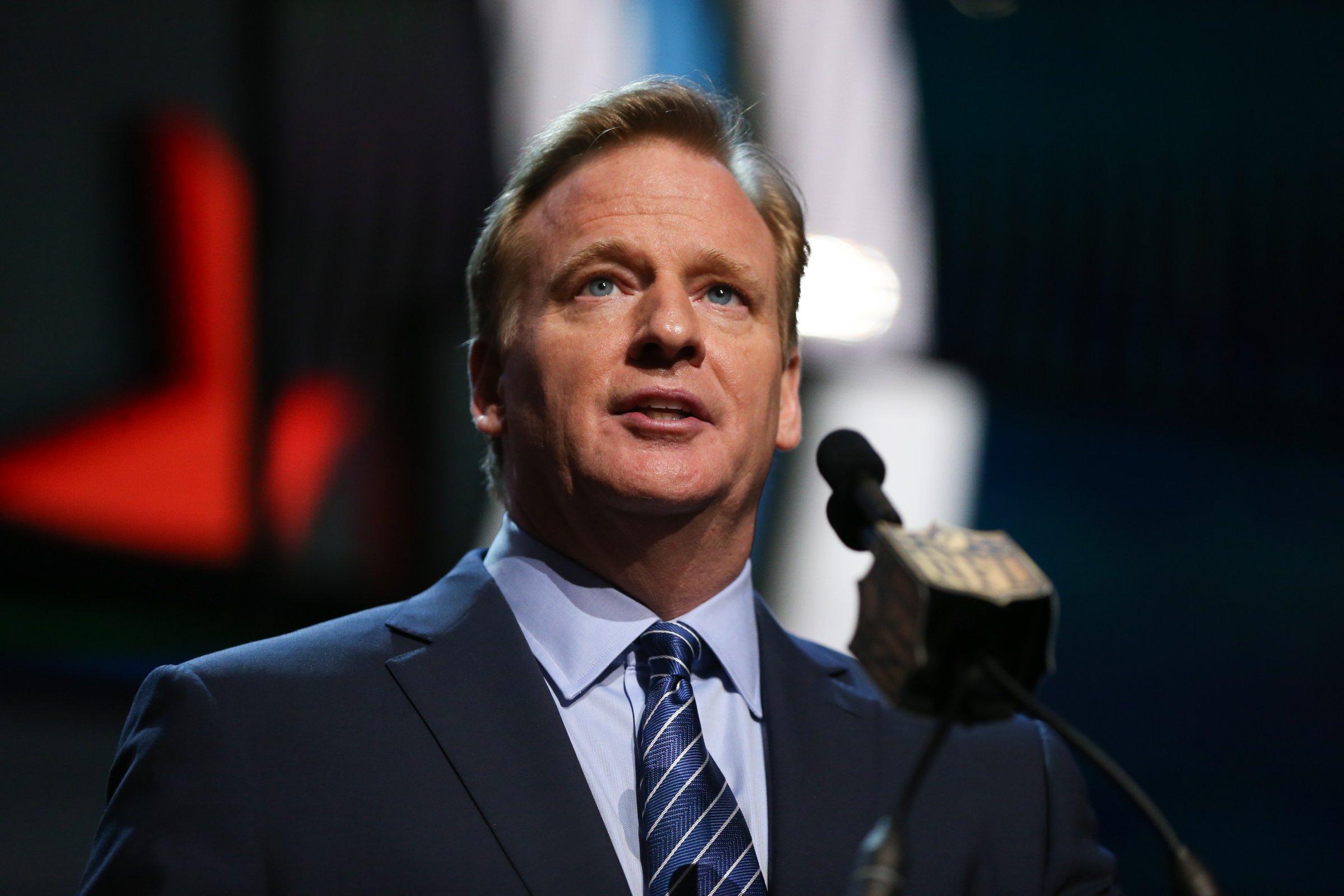

If the events of the last 14 months in the NFL have told us anything, it’s that commissioner Roger Goodell is in over his head. Charitable critics have figured him as a capable executive bungling his way through challenges whose difficulty he could not have anticipated (a star player punching his fiancée on tape but winding up essentially exonerated by the legal system; a marquee quarterback for a premier franchise accused of a vast cheating conspiracy, albeit one with dubious efficacy). And most critics have not been of this variety.

An outstanding extensive report Tuesday from ESPN’s Don Van Natta and Seth Wickersham primarily damns but kinda-sorta-a-little-bit-just-maybe-accidentally redeems Goodell for his handling of the two separate New England Patriots cheating scandals, 2007’s Spygate and 2015’s Deflategate.

The piece’s central revelation is that the Patriots’ Spygate-era taping of opposing coaches’ hand signals was a conspiracy more systematized and broad than previously known. Members of the team’s video staff who did the taping often disguised their true affiliation and said they were shooting footage for forthcoming documentaries. New England built dossiers matching opposing teams’ hand signals to the plays they ran.

And, the ESPN writers report, NFL executives including Goodell knew and concealed the true extent of the Patriots’ cheating regime. The league’s brisk investigation of New England meant that whatever punishment the Patriots received (the team was stripped of a first-round draft pick and fined $250,000 while coach Bill Belichick was fined $500,000) would not reflect anything beyond a superficial understanding of the team’s transgressions. When NFL executives turned up at the Patriots’ stadium to examine the evidence after the punishment had been meted out, they (not the Patriots) shredded documents and stomped on video cassettes. The ostensible goal was the immediate snuffing-out of any ill-gotten New England advantage. The actual goal was in all likelihood a coverup, for the sake of both an owner who had been very good to Roger Goodell and a league that didn’t want to see its so-called shield tarnished further.

Van Natta and Wickersham pick a lot of meat off that bone, explaining how Goodell stonewalled the inquiries of Sen. Arlen Specter and pressured at least one coach to endorse the league’s response to the crisis. And then they jump forward to the present day, reporting that Goodell’s dogged effort to sustain his flimsy four-game Deflategate suspension against Tom Brady is not the quixotic vendetta it has often seemed but instead an effort to placate the owners who felt he had been too soft on New England the first time around. Goodell in turn seems less like a moronic strongman and more like an executive pulled in too many directions by the various demands of his job.

I would be far from the first to suggest that Goodell surrender his role in player discipline. (In an interview with ESPN’s Mike and Mike, he said he was open to reducing his involvement but would not relinquish it.) That he is judge, jury, and executioner in the process, as other commentators have put it, remains an embarrassment to the NFL and gives the lie to any suggestion that its players enjoy the benefit of due process. There’s a reason the NFL has lost a string of appeals in federal court.

But the Patriots story exonerates Goodell at least somewhat by explaining that the league’s needs in 2015 are too many, and too divergent, for this man to run it. League revenue (TV deals, licensing and sponsorships) matters much more to the owners than when the gig was dreamed up in 1941. Under any executive but the most circumspect one, the game’s integrity necessarily takes a backseat to the league’s business operations. As a source told ESPN, “There are people who feel [Goodell] has made them a lot of money and they shouldn’t do anything. Others think, ‘He has embarrassed the league and if we had a better commissioner, we’d be making more money.'” (As if the only reason to avoid embarrassment is that you might make more money in doing so.)

Goodell ought to be free to do what to date he has done best—growing the business’s revenues through shrewd negotiations with media partners and sponsors—while someone else deals with the weightier questions of what’s good and fair and right for the game of professional football. This person could be anyone from a former player to a former coach to a former president, so long as the owners and NFL fans respect and trust him or her. There are names out there from the public-service world that might fit the bill: Tom Osborne, John McCain, Donna Shalala, Colin Powell.

The question is whether any worthwhile eminence, one who could choose from any number of positions in academia, nonprofits, or the corporate world, would cast his or her lot with a business as inherently blemished as the NFL. Football’s concussion problem will not dissipate soon; it may be unsolvable. If nothing else, that concern illustrates just how bad Roger Goodell has been at his job since last summer: He has made his easier problems seem like the hard ones.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jack Dickey at jack.dickey@time.com