The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, a show about a street-smart teen from West Philadelphia whose mom sends him to live with his conservative relatives (the Banks family) in Bel-Air, California, premiered 25 years ago this week. The sitcom, which ran from 1990 to 1996, launched the career of its star Will Smith, known as the rapper The Fresh Prince, along with many others.

With reruns still airing and the theme song still playing on dance floors and being remixed on YouTube, TIME catches up with award-winning composer and record producer Quincy Jones, 82, who was the show’s executive producer, and its creators (who were married at the time) Andy Borowitz, 57, author of the satirical column The Borowitz Report, and Susan Borowitz, 56, a former writer for Family Ties and the author of When We’re in Public, Pretend You Don’t Know Me. In separate interviews, the trio talks about why NBC was scared to run a show starring a rapper, how the show influenced pop culture and why not to get your hopes up for a Fresh Prince reboot.

How the show got started

Andy: I was under contract to create comedies for NBC, and the network wanted to develop a show for Will. Quincy Jones was one of the executive producers, and he had a lot of stories about bringing up his children in Bel-Air. According to Quincy, he received this phone message from one of his daughters who was away at camp: “Dad, the water here sucks. Please FedEx Evian.” So the idea for the show was to drop Will into a family like Quincy’s.

Susan: I had been reading this New York Times series on being black in America, and there was this one article that really disturbed me about how being successful in some corners of the American black experience was akin to selling out. It was a really upsetting story because it was like, how do you get out of the poverty, the more violent neighborhoods, if succeeding is considered tantamount to turning your back and becoming white? So I said to Andy, why don’t we make it about that? Why don’t we make it about how there are all these different ways of being black?

Twenty five years ago, there was a sense of this monolith of a black experience, that there was one kind of black American, and they all think alike and do the same thing. We liked the idea of challenging that.

Quincy: If the show allowed people to have a better understanding of our culture, all the better.

How two white television writers made a show about a black family

Andy: In terms of the characterizations of the black characters, I was naturally concerned, as a white writer, about getting things wrong.

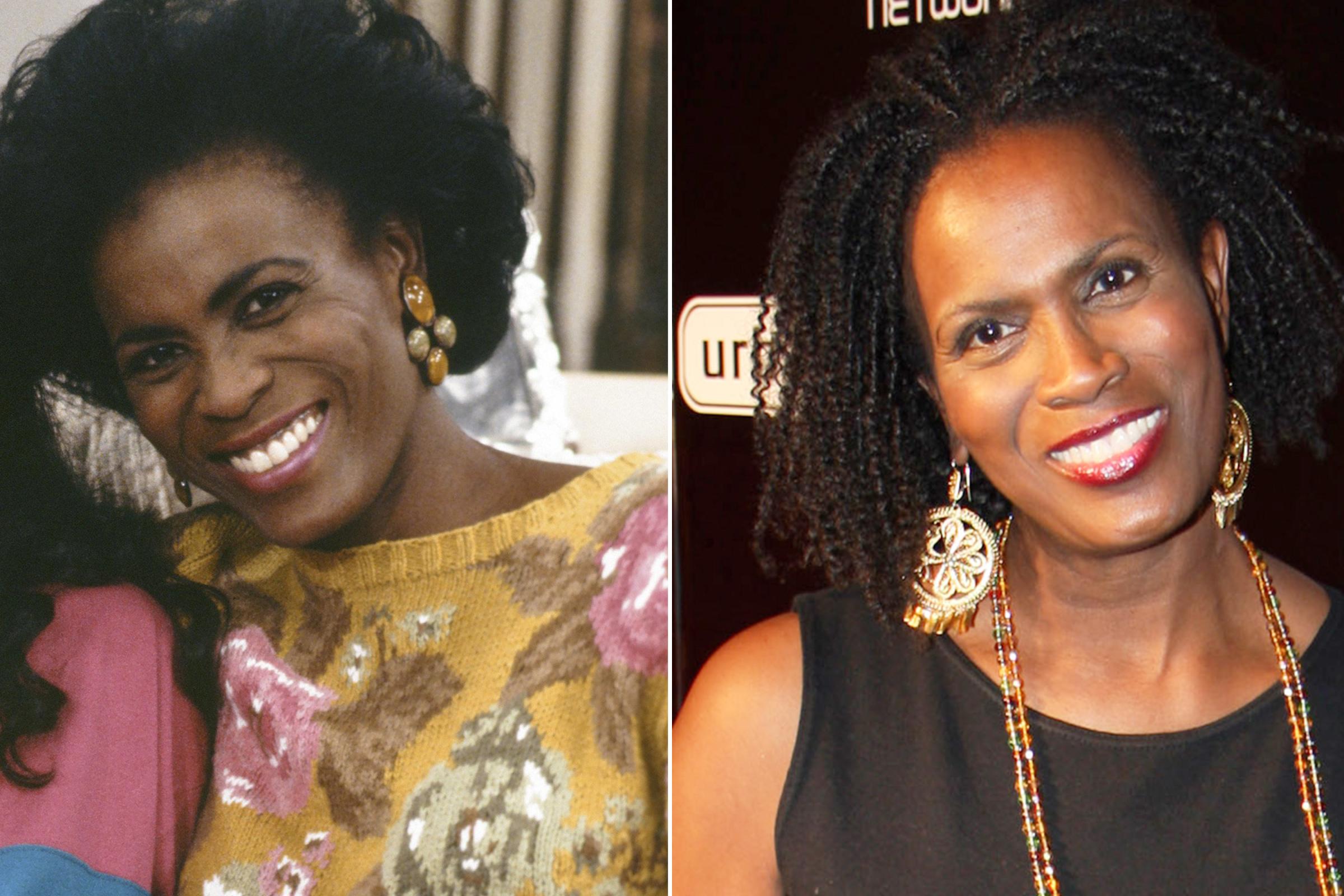

Susan: We made sure we had a lot of black writers and black crew people and were very open about “Hey, if we get something wrong, let us know.” How many white writers grew up around so many black families that they’re able to see the nuances? For instance, one of our white writers wrote a Thanksgiving episode with pumpkin pie, and the black writers laughed and said a black Thanksgiving has sweet potato pie. We didn’t know if Hilary [Karyn Parsons] was accurate, but Quincy called his daughters “black American princesses” and said, “You’ve got have the daughters be BAPs.” Oh, okay.

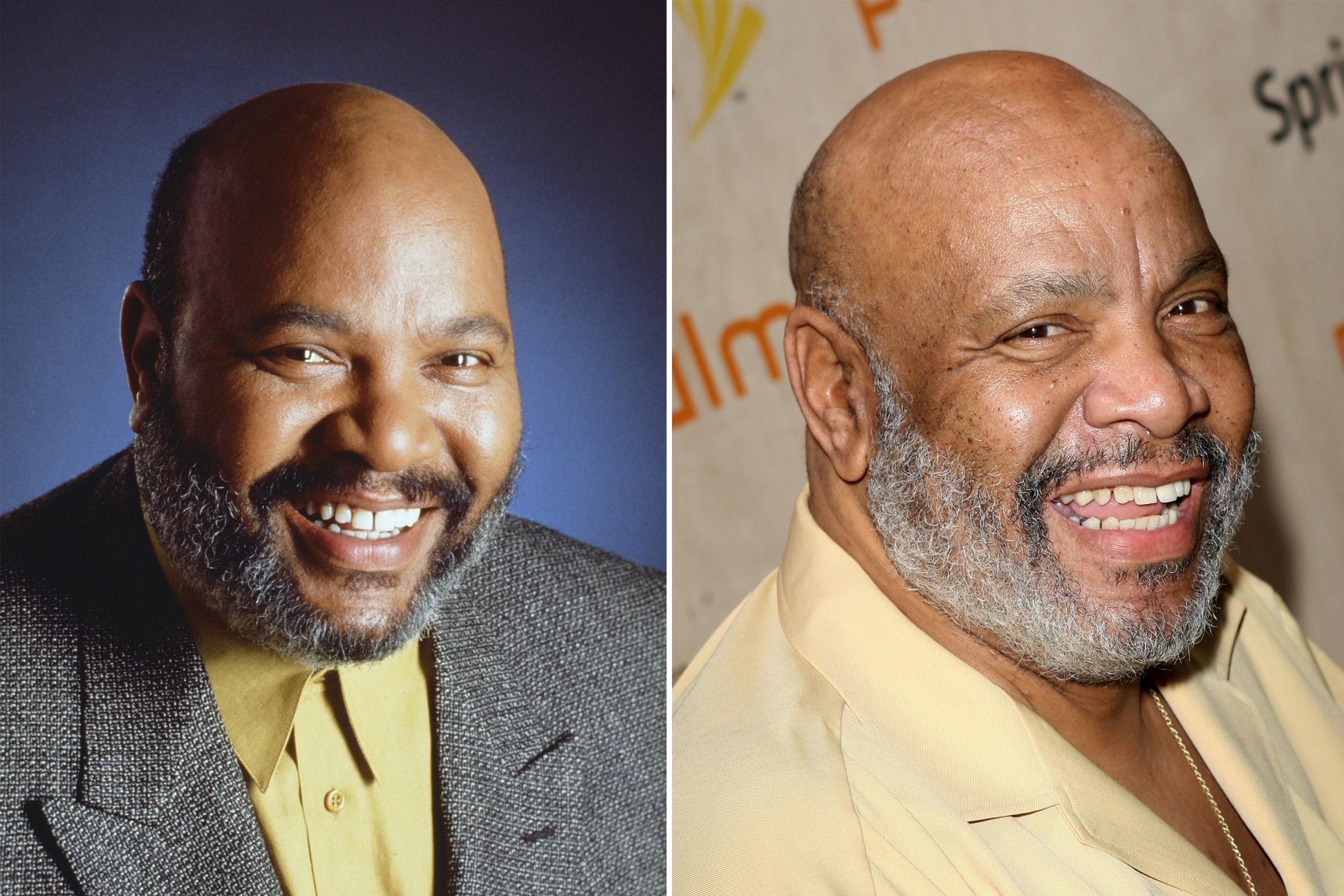

Andy: One thing that’s interesting about the characters on Fresh Prince is that they didn’t have a lot of obvious antecedents. We hadn’t seen black actors portraying English butlers, millionaire corporate lawyers, and Princeton-bound preppies in 1990. And one thing Quincy stressed, which was so important, was that the characters had to have duality: Uncle Phil [James Avery] was excited to live in the same neighborhood as the Reagans, but he was also proud to have heard Malcolm X speak.

Quincy: The Cosbys were affluent, but the Banks’ were wealthy. I don’t think you’d ever seen a wealthy African-American family on television until Fresh Prince, and you definitely hadn’t seen a kid from the hip-hop generation until Fresh Prince.

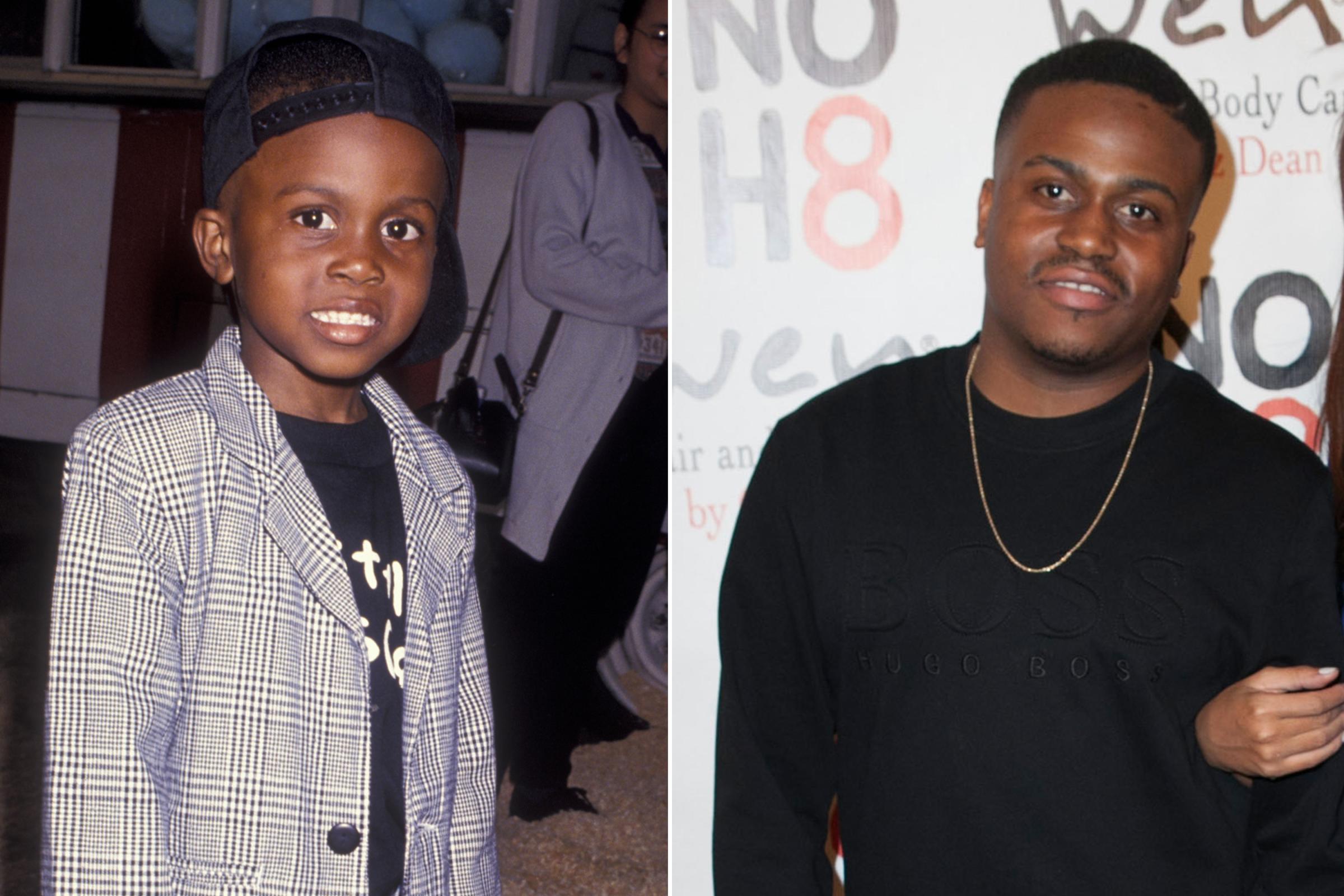

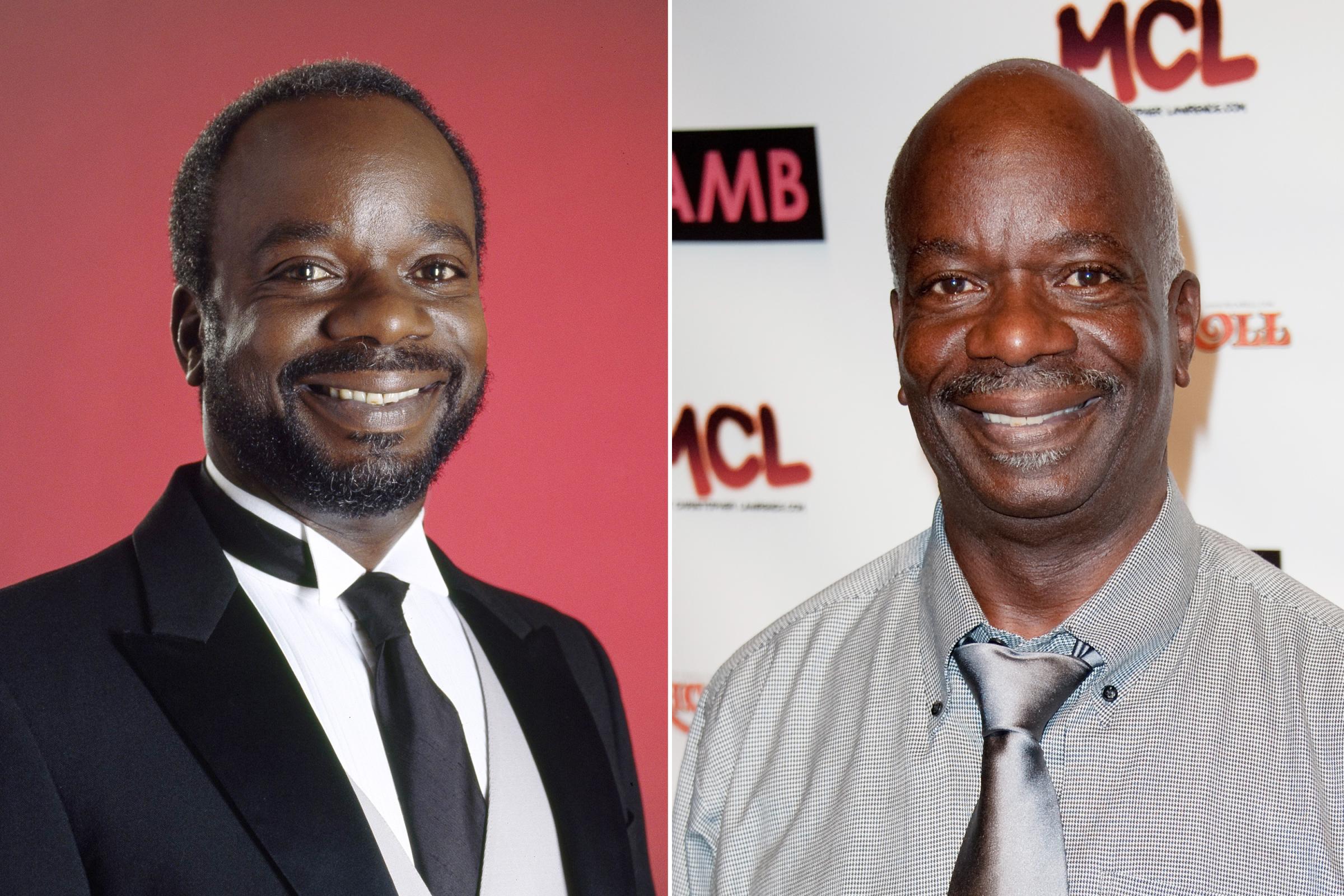

See the Cast of 'The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air'

How Will Smith became a star

Quincy: Will had never acted before Fresh Prince, but after a 15-minute read through, we knew he was our guy. You could tell that there was no mountain too high for him, and I’m so proud of everything that he has achieved. But he was surrounded by an absolutely stellar cast, and a great writing staff and crew, and that should never be overlooked.

Susan: The network also would listen to Will. NBC wanted us to make Carlton [Alfonso Ribeiro] cool, and we said, “No, he’s a great foil,” and won on that because Will weighed in and said, “Absolutely not, this is what makes the comedy.” [The network] didn’t want to hire Joseph Marcell, who played Geoffrey the butler, because he wasn’t a name. They wanted us to go with Ron Glass who was on Barney Miller. Luckily, Will said, “No, I like the British guy with the big nose.”

How the show influenced pop culture

Quincy: I think Fresh Prince and the success of the show was the final piece that cemented hip-hop into the pop culture lexicon. Throughout our history, African-American music and culture has always been a barometer for a coming social change in America – the Jazz Age in the 30’s and 40’s, be-bop in the 50’s, rock-and-roll which is really the blues in the 60’s, the empowerment movement of the 70’s with Marvin Gaye, Aretha, James Brown and others, and hip-hop in the late 80’s. I had a lot of the rappers on my album “Back on The Block” in 1989, so I was very aware of the shift that was happening with hip-hop and its genesis early on. It was the next evolution of our music.

But you have to remember what was going on in the country at the time culturally. Hip-hop was blowing up, selling millions of albums a week. The kids, both black and white, had cloaked themselves in the culture. You had white kids in Iowa walking around with their baseball caps on backwards, but the establishment, as usual, was freaking out about the reality of the message in the music. You had C. Delores Tucker, Tipper Gore, and other groups doing everything possible to kill the music, but they couldn’t. The kids had found a voice in hip-hop that spoke to them.

Susan: By the time we moved back [to the East Coast], we’d hear white kids on the playground using these words we wrote into scripts, and it cracked us up — these wealthy Westchester white kids using “Yo, dawg.” A lot of the language crossed over into white suburban culture. Some rappers were very angry Will had done this. They felt he had watered down their culture for this white middle class audience.

Andy: I’ve seen the show referred to fondly as a “’90s time capsule” and the wardrobe described as “typical ’90s fashions.” I think both of those assessments are wrong. The show was extremely stylized and kind of inhabited a universe of its own. If you look at other sitcoms from that decade, they look nothing like Fresh Prince because everything in the show is so amped up – the huge mansion, the English butler, Carlton’s dancing. Having said that, I’m sure there are kids who watch it now and think they’re seeing what life was really like in the ’90s. That’s hilarious to me.

How the show changed television

Quincy: In business, particularly in Hollywood, success makes a lot of fear go away, and I think the success of Fresh Prince gave the networks permission to move in directions they may not have normally. We followed Fresh Prince with In The House which starred LL Cool J, and that show ran for three years.

Andy: I didn’t see the show as being trailblazing, but it sort of turned out to be, since it was the first network show to feature a hip-hop star. That might not seem like a big deal in 2015, but in 1990 it was. At the time, the media were freaking out about controversial rappers like 2 Live Crew, and even though Will’s rapping had zero in common with theirs, NBC was irrationally nervous about how the network audience would respond to a show starring a rapper. As it turned out, the show was the highest-rated new sitcom in its first season. In 1990 I had no idea that, 25 years later, it would still be on TV and people would still be enjoying it.

Susan: It was surprisingly forward-thinking. The show launched a lot of careers. It started a wave of black shows. Ironically, BET was harmful to mainstream black network shows because it became the place where black shows went when you’d pitch. It was very easy for networks to say, “This sounds more like a BET show than a network show.” Then Shonda Rhimes comes along, earns her credit doing white shows, and then she’s able to do How to Get Away with Murder. I have such respect for her.

With Empire and Blackish, now apparently they’re asking for black shows again. My fear about this newfound black programming is that the networks will say, “Great, so to repeat the success of Empire, what we have to have is an all black cast, shady dealings, and danger.” But it may not be good. And to repeat Blackish? “What we need are more black family comedies.” But they may not be good. And if these fail, they’re just say, “Oh, I guess Blackish was a one-off, Empire was a one-off, so we’re not going to do those anymore.” They won’t persist in actually broadening.

How likely the chances of a Fresh Prince reboot are

Andy: They’re doing a fish-out-of-water show that’s not a continuation of Fresh Prince in any way. I’m not involved with that show. As for actual TV reboots, which are all the rage right now, I oppose them on principle. I think the reboot of The Brady Bunch as The Brady Bunch Hour variety show in 1976 should be a cautionary tale for all of us.

Susan: I’d be interested to see how [Will Smith would] do a fish-out-of-water situation because things are so different in good ways and bad ways. In good ways, I think America recognizes now that there can be Ben Carsons and Kanye Wests, and I don’t think people blink an eye, especially after Obama. The bad thing that’s happened in America that I think would be a challenge for this show: How do you talk about the black experience without dealing with Ferguson and police brutality? How do you do that in a comedy? It’s one of the reasons I wouldn’t be involved even if he asked me, because I would say I don’t think this is a winning…I don’t think this is an easy thing to do.

How The Fresh Prince would look if it premiered today

Susan: Honestly, when I think about doing a reboot of this, it all becomes very schematic to me, like going backwards. Unless you do the Rachel Dolezal story. That’s the modern thing — the person who is masquerading.

Andy: I guess if the show were premiering today, cousin Hilary would have a very active Instagram account and would be constantly taking selfies, and… as I describe this … it sounds truly horrible. Why are you asking me to wreck Fresh Prince, Time magazine? Let’s just stick with the ‘90s version, okay?

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com