The southeast is a strange place for a political pilgrimage. Presidential candidates favor states that are first or fickle, and the heartland of the Republican Party is neither. Yet for a week in August, Ted Cruz crisscrossed the Bible Belt, dropping in on churches and chicken joints in campaign backwaters like Birmingham, Ala.; Chattanooga, Tenn.; and Bartlesville, Okla. The first presidential debate had boosted his poll numbers and turbocharged his fundraising. Big crowds greeted him like a gridiron legend. But this was no victory lap. The Texas Senator has a new Southern strategy. Seven Southern states with about a third of the delegates needed to win the nomination are likely to be up for grabs on March 1, a Super Tuesday bonanza Cruz calls the SEC primary. So while rivals jockeyed for scraps of territory in Iowa and New Hampshire, Cruz barnstormed the nation’s reddest precincts in a bus with Right turns only plastered above the bumper.

The message doubles as a campaign mantra. Rafael Edward Cruz, 44, has sought to position himself as the most conservative member of a very conservative field. In recent weeks alone, he has dismissed global warming as a fiction cooked up by government stooges, saluted Donald Trump for his rants against Mexican border crossers, called GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell a liar and hinted at a fall standoff over Planned Parenthood funding that could once again shutter the federal government. “If you’re running for President, you get to decide what your narrative is, and that narrative is a clarion call,” says a senior adviser. “He’s a ‘f-ck the police’ guy.”

All this cage rattling is a conscious tactic. Most GOP consultants think the way to win the White House is to expand the party’s contours, courting Hispanics, women, millennials and other Democratic-leaning groups. Cruz is convinced there are enough true believers to push a proven warrior into the White House.

“Voters should ask every candidate, Show me where you’ve stood up and fought,” Cruz explains, digging into a double cheeseburger with jalapeños at a Whataburger outside Houston. The people who stop him on the campaign trail, he adds, all say the same thing: “Thank you for fighting for me. Nobody else is fighting for me.”

The Texas Senator has likened this hard-line style to a “disruptive app.” The pitch has attracted plenty of seed money–more than $50 million between his campaign and affiliated super PACs, a total that ranks second only to Jeb Bush’s. Cruz boasts that he is the rare true conservative with the fundraising firepower and organizational muscle to slug it out with the GOP’s Establishment favorites through a grinding national campaign. Instead of softening his rhetoric, he believes a pure conservative message can drive millions of disaffected white and evangelical voters back to the polls. The bet spooks Republican consultants, who see in Cruz’s uncompromising candidacy the threat of ruin. “It’s a huge gamble on the future of the party,” says Ari Fleischer, a former White House press secretary who worked with Cruz on George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign. “That’s what’s at stake.”

Cruz describes politics through a lens of perfect moral clarity. The characters in his narratives are good or evil, courageous or corrupt. His own story is more complicated. Cruz is a constitutional scholar who commands a populist army, a careful tactician who picks long-shot fights. The mystery that’s most confounding is how a man who spent much of his professional life inside the clubby Republican establishment evolved into its fiercest critic. Cruz offers a simple answer. “I grew up a movement conservative. That’s who I am,” he says. “I don’t have to fake it.”

It was early July, the first day of the promotional tour for Cruz’s newly released memoir, A Time for Truth. The candidate was savoring a rare moment of downtime between book signings in Texas. To unwind between campaign stops, he plays iPhone games like Candy Crush and Plants vs. Zombies. He trawls Twitter to read the invective hurled his way, sometimes chuckling as he quotes memorable insults aloud. He has a knack for mimicry, with a repertoire that includes impressions not only of statesmen like Churchill or John F. Kennedy but also of Homer Simpson, Darth Vader and Jay Leno. On Sunday nights, he plays cashier in a family game called Store, in which Cruz and his wife Heidi, who is on leave from her job as a managing director at Goldman Sachs to help the campaign, award toys to their two young daughters for good deeds they’ve done throughout the week.

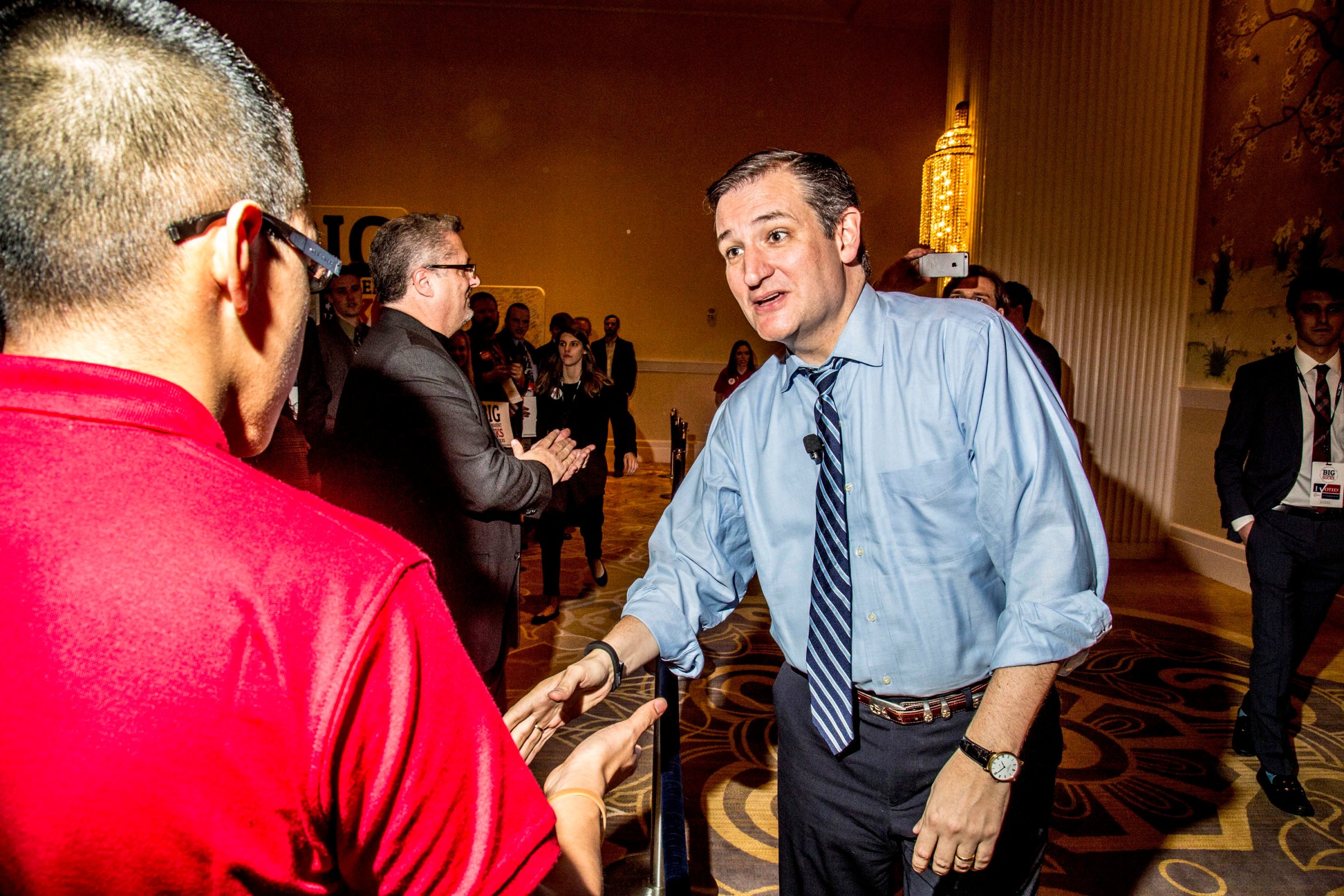

In front of a crowd, Cruz is as disciplined a performer as anyone in politics. His stump speech, delivered without notes or teleprompter, is precisely honed, down to the canned jokes and the pauses for emphasis. When he preaches to the party faithful, Cruz ditches the lectern and roams the stage, carving up his targets in tightly constructed paragraphs. There are no rambling asides, no rhetorical stumbles. He sprinkles his speeches with social cues–ain’ts and God-bless-yous and Chuck Norris jokes–that show the audience he’s one of them. No Republican candidate has a better ear for the angst and anger of the party base.

And he is relentlessly on message. In late June, I watched Cruz work a Dutch bakery in Orange City, Iowa, where the specialty almond patties retail for $1.50. He sidled up to a pair of preteen girls playing a card game called Trash and made small talk about how neat it had been to come of age with Ronald Reagan in the White House. Even in private, says a Cruz campaign staffer, “I almost feel like I’m getting talking points.”

Few politicians milk as much mileage from biography as Cruz. And not only his own. “When you’re raised as a little boy with an aunt and a dad who were imprisoned and tortured,” he explains, “standing and fighting for what you believe is drilled into your head from an early, early age.” Cruz’s father was a Cuban revolutionary who fought against Batista, fled to the U.S. with $100 sewn into his underwear, launched an oil business and has recently become an itinerant minister with a fervent Tea Party following. His mother was the first in her family to attend college, escaped clerical duties after graduation by refusing to learn to type and became a computer programmer instead. “Both of them demonstrated courage to stand up for principles,” Cruz says, “even when there was a price to pay.”

Cruz was born in Calgary, Alberta, where his parents worked in the oil industry, and moved to Houston as a child. Young Ted was still known as Felito when it dawned on his parents that they had an academic prodigy on their hands. At 13, he enrolled in an after-school program designed to inculcate the merits of free-market economics. By then his obsession with the Constitution had taken root. (“I was kind of a weird kid,” Cruz writes in his book.) As a sophomore in high school, he joined a performance troupe that toured Texas, mesmerizing audiences by scrawling its text on easels from memory.

At Princeton, Cruz was a national debate champion. He went on to Harvard Law, where he relished the flak he received as a rare conservative rabble-rouser. “Even at Harvard he was the scourge of the Establishment,” says Alan Dershowitz, a liberal law professor who recommended Cruz for his Supreme Court clerkship. “The constant has always been that he very much enjoys his role as a provocateur and as someone who stands for principle. I’ve warned my liberal friends: Do not think he is just an opportunist.”

Cruz was so keen to succeed at his clerkship that he took tennis lessons to improve his game at Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s weekly Thursday-morning doubles match. From there, Cruz spurned a bigger salary for a job at a small, politically connected Washington firm run by some of the conservative movement’s top constitutional lawyers. One of his clients was Representative John Boehner, then the No. 4 Republican in the House.

The entrée to elite GOP circles led to Cruz’s recruitment as one of the brainy “propeller heads” charged with crafting domestic policy for George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign. After the impasse on election night, he was dispatched to Tallahassee, Fla., to assist with the recount, joining the team of Republican superlawyers who clinched Bush’s spot in the White House. But when it came time to divvy up the spoils of victory, Cruz was blackballed from the job he desperately wanted as a senior adviser to the President. His cockiness had rubbed powerful people the wrong way. “Ted was sharp, humorous, incredibly smart and with an ego to match,” Fleischer recalls.

It was the first setback in a career that had been an uninterrupted string of successes. “I failed miserably,” Cruz says, riding shotgun in the black Chevy Tahoe SUV ferrying him to another book signing in Texas. “And there was no one to blame but myself.”

But it was also a gift of sorts, freeing him from the Republican establishment that became his foil. Cruz spent a few years bouncing around Washington before returning to Texas as his home state’s solicitor general. When he considered running for attorney general in 2009, he was still tight enough with Texas bigwigs to wangle an invitation to Kennebunkport for a meeting with George H.W. Bush.

But when Cruz launched a long-shot bid for the U.S. Senate in 2012, he campaigned as a self-styled insurgent. The reinvention prompts some Republicans to suggest the party-crasher routine is an act Cruz created as he watched the GOP rank and file lurch to the right during the early years of the Obama presidency. From the time he arrived in the Senate in 2013, Cruz grasped that pariah status in Washington can be a powerful weapon, so he wears his colleagues’ contempt as a badge of honor. His taste for skewering his own party often surprises even those familiar with his scorched-earth style. “The Senate, as bad as you think it is, it’s worse,” he tells voters. “They stand for nothing.”

If Cruz’s politics are guided by gut, his campaign is ruled by data. Its headquarters, in a spacious suite with sweeping views of the Houston skyline, contains brightly colored nooks designed to inspire Google-style collaboration. At the front of the office, near a children’s playroom strewn with teddy bears, sits a team of 12 data scientists working to divide primary voters into “psychographic clusters” on the basis of their personalities, interests and values. The goal is to determine their target audience and feed each segment a message calibrated to sway them.

It’s all part of a strategy that chucks the old model for an insurgent campaign. “It is unlikely to be possible for a candidate to do what some candidates in previous decades have done,” Cruz explains, “which is go camp out in an early state, spend a year there, throw a Hail Mary and get enough momentum to win the nomination.” The party has compressed the 2016 primary calendar into a few months in order to limit the damage the race inflicts on the eventual nominee. But with so many hopefuls like Cruz raising so much early money, the prospects of a costly, drawn-out fight are now very real. And Cruz is digging in for the long haul.

The campaign describes the race as a series of “brackets,” each of them mini-competitions for subsets of the GOP electorate. There is the Establishment bracket (with Bush, Chris Christie, John Kasich and others vying for supremacy), the libertarian bracket (a category of one: Rand Paul), the social-conservative contest (Mike Huckabee, Ben Carson, Rick Santorum) and the Tea Party crowd. Cruz’s plan is to corner the market for Tea Party conservatives and compete for swaths of the evangelical and libertarian vote. And even if he stumbles in the first few states, he sees the cascade of Southern contests in March as an opportunity.

“It’s entirely possible that one person wins Iowa, a different person wins New Hampshire, and a third wins South Carolina,” Cruz says. “Which means then you’re fighting trench warfare nationwide.” If it all unfolds as planned, he expects to emerge around mid-March as the conservative alternative to the Establishment favorite.

“Don’t underestimate him,” says Republican strategist Ed Rollins. “I don’t know whether he wins this thing or not, but he certainly is going to be someone who’s in the top four or five and probably stays in to the end. He’ll move out of this campaign as a leader in the party.”

The strategy of staking out the most conservative position in every political skirmish may boost Cruz in a primary, but it often puts him on the wrong side of public opinion. His embrace of Trump is a case in point. Virtually every other GOP candidate has denounced the developer’s inflammatory rhetoric. But Cruz takes a similar hard-line position against “amnesty” and hopes to scoop up Trump’s supporters when their summer fling fades. It’s all a reflection of Cruz’s abiding belief that the most powerful force in politics is fidelity to principle. “When he takes on an issue,” says campaign manager Jeff Roe, “we ain’t backing up.”

Cruz is a fan of the ancient Chinese military general Sun Tzu, whose famous aphorism holds that battles are won by choosing the ground on which they are fought. “What I ask activists to do is to pick the 10 or 12 most important fights of the last several years,” Cruz says as his SUV wheels toward another book signing in Texas. On every big conservative battle, he says, from Obamacare to government spending to religious liberty, “I’ve been leading the fight.”

History suggests the race for the presidency is more than a purity contest. But if the 2016 battle is waged on those grounds, it may favor the fighter who only turns right.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com