One hundred years ago this month, a 5-year-old boy spread a quilt and lay with his parents on the grass of the backyard of their house in Knoxville, Tenn. On this summer night, he listened to the music of the evening — the murmur of neighbors talking on porches, the clop-clop of horses on the street, the hissing of hoses watering lawns, the rasping of locusts and crickets, and the flopping of a few frogs in the dewy grass. He watched the last fireflies flicker out and wondered who he was.

How do we know this? Because James Agee wrote it in his rapturous prose-poem, “Knoxville: Summer, 1915,” in 1938 at the age of 28. Agee said later that he had written its five pages in a breathless 90 minutes, as a way to experiment with free-form writing. Originally published by the Partisan Review, and later placed as a prologue to his posthumous novel, A Death in the Family, it lives on as a contemporary classic, the most ecstatic piece of writing ever composed about an American summer. Samuel Barber set it to music for soprano and orchestra in his composition, Knoxville: Summer of 1915.

That summer was Agee’s last in an intact family. A year later, in 1916, his father was killed in an automobile accident. Agee himself would die of a heart attack in the back seat of a New York City yellow cab at the age of 45 in 1955. At the time, he was best known for his work as the film critic for TIME (and later The Nation) and for his screenplays (The African Queen, The Night of the Hunter). But Agee wasn’t the only one for whom that summer would be significant: thanks to his writing, 1915 has something to teach all of us.

What do we make of “Knoxville: Summer, 1915” now? It is nostalgic and sentimental yet also undeniably beautiful. In Agee’s imagination, a nozzle on a hose is a Stradivarius:

First an insane noise of violence in the nozzle, then the still irregular sound of adjustment, then the smoothing into steadiness and a pitch as accurately tuned to the size and style of stream as any violin. So many qualities of sound out of one hose … the almost dead silence of the release, and the short still arch of the separate big drops, silent as a held breath, and the only noise the flattering noise on leaves and the slapped grass at the fall of each big drop. That, and the intense hiss with the intense stream; that, and that same intensity not growing less but growing more quiet and delicate with the turn of the nozzle, up to the extreme tender whisper when the water was just a wide bell of film.

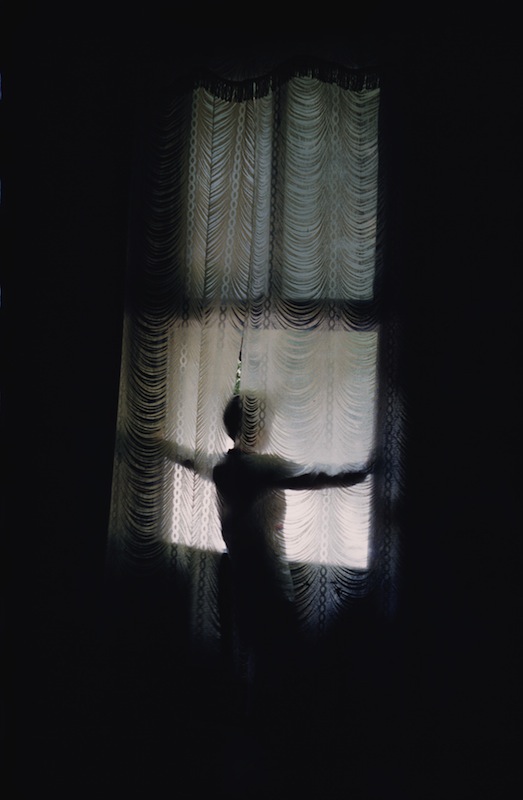

Agee was describing the lost world of porches and the closely knit communities that shared them. The shady, street-front verandas that were once an amenity on every American house were killed off by air-conditioning. By the 1950s, builders stopped putting porches on new houses, and families retreated indoors to their televisions. Today grandparents who once sat in the rocking chairs on the porches of Knoxville are just as likely to be in an assisted living facility. And the people walking down the street are making eye contact not with their neighbors but with the smartphones in their hands.

All of these changes would appear to make Agee’s writing very dated today — the verandas are gone. Yet what endures is perhaps more important: the nagging sense of lost community that they represented. Agee put into words and art a vision of small-town America that we often scoff at as a cliché…yet we continue to return to it. That it can still move us is proof that, while porches may go out of style, the deeper things that bind us endure. We still have something to learn from those summer evenings in Knoxville.

Pia de Jong is a Dutch novelist and newspaper columnist who moved to America three years ago. Her memoir, Charlotte, will be published by Prometheus in the Netherlands in January 2016. Landon Jones is the former editor of People and Money magazines and the author of Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation (1980) which coined the phrase baby-boomer.

Read TIME’s original review of A Death in the Family, here in the TIME Vault: Tender Realist

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com