As classified documents went, the Pentagon Papers were such dry reading that almost no one made it all the way through them — including Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s national security adviser and chief strategist on the Vietnam War.

When the 40-volume Pentagon report on America’s entanglement in the controversial war was delivered to reporters, however, it became the WikiLeaks of its day: “[t]he most massive leak of secret documents in U.S. history,” according to TIME’s 1971 account.

But even after the study’s revelations became front-page news in the New York Times, few lay readers could get excited about the story, which TIME described as “six pages of deliberately low-key prose and column after gray column of official cables, memorandums and position papers.” Most Americans only understood the scathing significance of the report when they saw how hard the Nixon administration fought to keep it under wraps.

What followed was a historic clash between the Executive Office and the Fourth Estate: For three weeks, the White House battled in court to keep the Times and the Washington Post from publishing stories based on the leaked documents, which revealed staggering incompetence and deception on the part of both the Johnson and Nixon administrations. The White House argued that publishing the information jeopardized national security; the newspapers argued that the public had a right to understand the machinations that had led the nation into its most unpopular and unsuccessful war.

In the end — on this day, June 30, in 1971 — the Supreme Court sided with the press and ruled that the newspapers could immediately resume publishing the classified reports. The 6-3 vote marked deep divisions within the court, however, prompting the justices to “[vent] their opinions in nine separate opinions,” as the Post put it the day after the ruling. TIME summarized the differences between their takes on the case:

Three of the Justices—Hugo L. Black, William O. Douglas and Thurgood Marshall—contended that there can be no exceptions to the First Amendment’s press freedom; no matter what the potential impact on the nation, prior restraints on news cannot be imposed by Government. Another trio composed of Justices Potter Stewart, William J. Brennan Jr. and Byron R. White took a middle position, contending that the First Amendment is not absolute and a potential danger to national security may be so grave as to justify censorship. However, they agreed that this had not been demonstrated in the Times and Post cases.

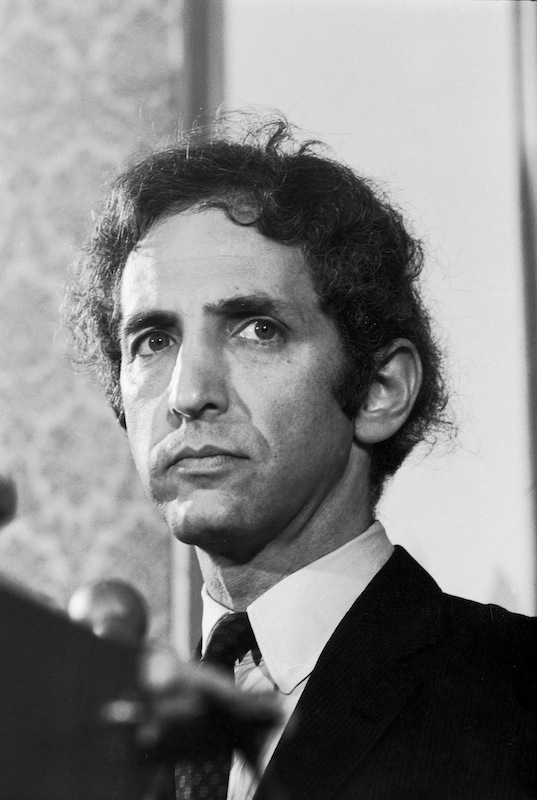

And while Daniel Ellsberg (who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the press by sneaking them out of his office safe, one volume at a time, to be Xeroxed by a colleague’s girlfriend in all-night copying sessions) initially faced felony charges for his role in the leak, there were many who commended him for his courage as a whistleblower.

The charges against Ellsberg were dropped in 1973, but the Pentagon Papers themselves were only declassified four years ago, in 2011. Ellsberg told the Times he believed they still held valuable lessons for the American populace — although he found it even more unlikely that anyone would wade through the 7,000-page report 40 years after it was leaked.

“The rerelease of the Pentagon Papers is very timely, if anyone were to read it,” he said.

Read TIME’s 1971 cover story on the Pentagon Papers, here in the TIME archives: The Secret War

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com