The two-story sandstone house at the corner of Hope Avenue, a quiet cul-de-sac in the northern English city of Bradford has been empty for months. Last fall, Zohra Dawood, 32, left the house with her two daughters and moved into her father’s home a little over a mile away. Her husband stayed on for a few weeks before returning to his own father’s home, 4,000 miles away in Pakistan. Neighbors say Dawood changed the locks soon after, but never returned. What happened between members of the family in that house may provide clues for police and relatives who have spent more than a week trying to understand why Zohra Dawood and 11 other family members went missing and are believed to be in Syria.

Dawood, along with her two sisters, Khadija, 29, and Sugra, 34, and their nine children first left the U.K. at the end of May for a pilgrimage to the Saudi city of Medina. They reportedly boarded a flight to Istanbul, Turkey on June 9 instead of flying back to Bradford as planned on June 11. According to a smuggler working for the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) quoted in BBC reports on Friday, the family of 12 has already crossed into Syria in two separate groups.

They are not the first Bradford locals to attempt to travel to Syria. The sisters’ younger brother, Ahmed Dawood, 21, has reportedly been fighting alongside extremists there for more than a year. And on Wednesday, a court heard the case of Bradford teenager Syed Choudhury, 19, who plotted to join ISIS and pled guilty to preparing acts of terrorism.

Situated 200 miles north of London amid Yorkshire’s rolling hills and wild moorland, Bradford is home to some of England’s most deprived neighborhoods, with high unemployment and lower levels of education than the national average. Its golden era as the center of the Victorian wool trade – which helped build the towering neo-Gothic buildings at the heart of the city – is long gone. In 1995, American travel writer Bill Bryson opined that Bradford’s sole purpose “is to make every place else in the world look better in comparison.”

Back when Bradford’s textile industry was booming, the city drew waves of immigrants from South Asia. Now, more than a fifth of Bradford’s 526, 400 people are Pakistani by origin, the Dawood family among them. The streets of the Little Horton area of Bradford where they live are dotted with sari stores, mosques and bakeries selling naan bread and South Asian sweets. It’s not hard to see why the city has earned the nickname “Bradistan.”

The siblings’ parents – Mohammad Dawood and his wife Sara Begum – have at least eight children, all born and raised in Bradford. In a statement, the members of the family still in Bradford said they were devastated by the news and that they did not “support the actions of the sisters leaving their husbands and families in the U.K. and of taking their children into a war zone where life is not safe to join any group.”

Although there are numerous cases of foreign fighters taking children with them to ISIS-controlled territory, the sisters and their children constitute the largest family group known to have left the U.K. to join the extremist group in Syria. The three women seemingly defied the wishes of their parents and husbands in following their brother to Syria. Khadija, Zohra and Sugra apparently felt stronger ties to one another and their brother in Syria than to the family members they left behind in Bradford.

“An essential aspect of extremism is that it has to have social support,” says Arie Kruglanski, a professor of psychology and co-founder of the Center of Terrorism at the University of Maryland. “It’s very important that these women left as a group, as a network of sisters supporting their brother. Groups tend to polarize around values, and as a result, they tend to be much more extreme than individuals,” he says. Because families are very close-knit, it’s especially difficult for European security agencies – who are already facing a diverse array of threats – to penetrate these networks.

John Horgan, incoming professor of Global Studies and Psychology at Georgia State University, adds that there is relatively little security officials can do to prevent entire families from traveling together. The idea that the nine Dawood children could soon become “cubs of the caliphate”, as ISIS dubs its junior recruits in internal and external propaganda, is an unsettling prospect. Horgan believes there will be more such cases in the future. “ISIS is preparing for the future and what they’re trying to do is groom the next generation of fighters,” he says.

One aspect of the radicalization process that experts know relatively little about is timing. “There has to be some kind of push factor,” says Horgan, who has been studying terrorism for twenty years. “A family dynamic, a trigger factor in a personal relationship, something to make someone leave the sidelines and actually consider going out there.”

Whether there was a series of triggers or if the disappearance of their younger brother was enough to motivate the women to leave their Bradford homes is not yet clear. During an emotional appeal to their wives at a press conference on Tuesday, Akhtar Iqbal appealed to his wife, Sugra, and five children aged between three and 15. “I miss you, I love you, I can’t live without you,” he wept. Khadija Dawood’s husband of 11 years, Mohammad Shoaib, also broke down as he begged his wife to bring their 5-year-old son and 7-year-old daughter home. “We had a perfect relationship, we had a lovely family. I don’t know what happened,” he sobbed.

Zohra Dawood’s husband, Zubair Ahmed, was absent; he was in Pakistan. If he had been present Ahmed would have been unlikely to speak of having a perfect relationship with his wife. His marriage to Zohra Dawood had broken down several months earlier. Reached by telephone on Wednesday, he told the BBC he had moved back to Pakistan after his wife “shunned” him and that he did not know of her plans to leave for Syria.

In conversations with TIME, Zohra Dawood’s neighbors paint a portrait of a private woman who likely turned to her siblings for support once her brother left the country and her marriage broke down.

Zoota Khan, 74, who lived next door to the couple since they moved onto the street in 2009, says the trouble all began once Ahmed Dawood left for Syria. “He was her most important brother and she was very upset,” says Khan, whose own family comes from a village in the same northern district of Pakistan as Zubair Ahmed. He tells TIME that Ahmed came over directly from Pakistan for his arranged marriage to Dawood, his first cousin.

Few Hope Avenue residents say they knew Zohra Dawood well but neighbors describe her husband warmly, saying he was a kind and caring father. “The wife kept indoors. It was the dad who was around, who’d give you the time of day,” says Sharon Wood, 43, who has lived on the street for 10 years.

Alex Firth, 37, says she only ever saw the couple together if they were getting in the car to go somewhere. “For a while, I thought Zubair was a single dad. He used to play outside with the girls, help them with their schoolwork, even do their hair. He really did everything. I never really saw any sign of affection from their mother.”

Another neighbor, a 31-year-old Pakistani woman who asked to remain anonymous for fear of backlash from the community, says Dawood had confided in her last summer that she was unhappy in her marriage and that she and her husband no longer shared a bedroom. She says Dawood also mentioned that she was planning to move to Saudi Arabia. “Zohra told me this country was changing too much, and that she was going to take her daughters away because she didn’t see their future here anymore.”

It remains unclear what finally prompted Dawood to leave her husband last fall. Ahmed told his neighbor Khan it was a misunderstanding and he was praying she would come home. In November, a few weeks after his wife left, Ahmed returned to his hometown of Tajak, about 60 miles west of Islamabad, to take care of his elderly father, who suffered a stroke. “He calls from time to time to ask if I have seen the children, how they are doing,” says Khan.

The Pakistani neighbor who asked to remain anonymous, says her children regularly attended Quran classes in Dawood’s home and were upset to hear the news of Dawood’s disappearance. “Zohra had real Islamic knowledge. She knew much more than us,” she says. By all accounts, the couple were religious. But whereas Dawood usually wore a headscarf with Western clothes, once she moved back into her father’s home she was only ever spotted wearing a full veil and gloves.

Surprising as it may seem, Horgan says research on radicalization has shown that sibling bonds trump ideological bonds time and time again. Psychologists tell TIME that strained personal relationships can often strengthen sibling bonds. The fact that the Dawood sisters always lived within walking distance of one another – and both Zohra and Khadija even shared the same family house for the past seven months – make it more likely that they saw themselves less as part of nuclear family units with their husbands and children, but rather as part of an extended family network. Understanding these bonds may well be essential to making sense of what drew the sisters together as they made their decision to leave for Syria.

As this sprawling saga plays out, more and more questions will emerge. Many will likely never be answered. And for the husbands devastated by the disappearance of their wives and children, it’s all too clear that the ties that bind a family can quickly become the ties that destroy them.

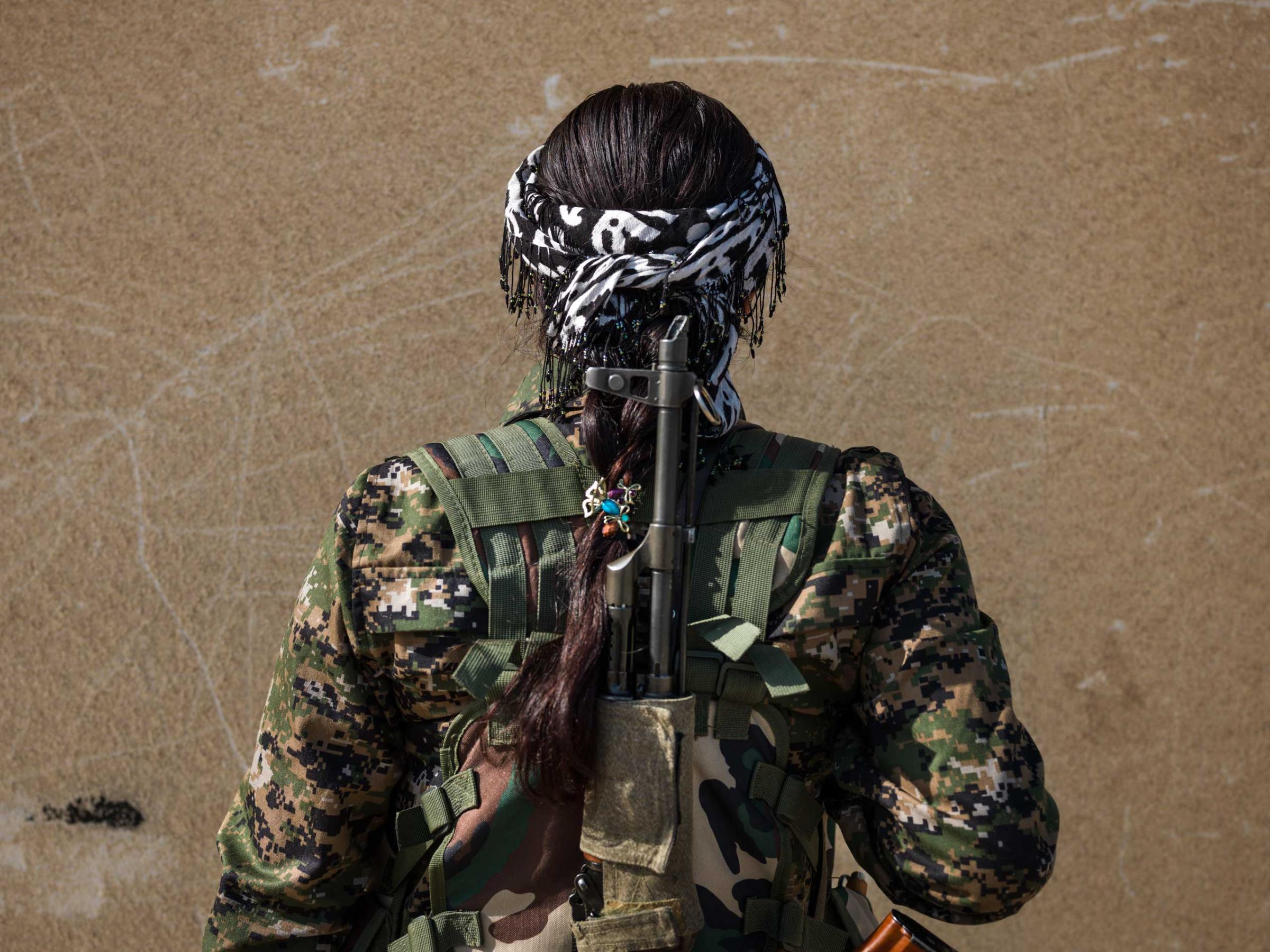

Meet the Kurdish Women Taking the Battle to ISIS

![18-year-old YPJ fighter Torin Khairegi: “We live ina world where women are dominated by men.We are here to take control of our future..I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been matryred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path." Newsha Tavakolian for TIME Zinar base, Syria "I joined YPJ about seven months ago, because I was looking for something meaningful in my life and my leader [ Abdullah Ocalan] showed me the way and my role in the society. We live in a world where women are dominated by men. We are here to take control of our own future. We are not merely fighting with arms; we fight with our thoughts. Ocalan's ideology is always in our hearts and minds and it is with his thought that we become so empowered that we can even become better soldiers than men. When I am at the frontline, the thought of all the cruelty and injustice against women enrages me so much that I become extra-powerful in combat. I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been matryred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path."](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/kurdish-women-fighters-syria-isis-newsha-tavakolian-09.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Naina Bajekal / Bradford at naina.bajekal@time.com