A full three decades before a 35-year-old British computer scientist named Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web, forever changing the way humans share and consume information (translation: cat photos), a young, visionary designer in Chicago created a device that he called, simply and evocatively, a “knowledge box.”

As LIFE magazine described the contraption to its readers in a September 1962 issue—in language similar to that used by both digital-age proselytizers and tech skeptics today—the knowledge box appeared to be an invention that would either help our willfully self-destructive species gain knowledge faster and more easily than ever before, perhaps allowing us to at least delay our extinction . . . or it might just hasten our inevitable demise.

You know, either way. Whatever.

As the imagination of many men creates a fantastic new world [LIFE wrote], the danger is that individual man may soon find himself lost in it. He may be expert in his own special field—microbiology, perhaps—but otherwise remains an ignoramus. New teaching techniques and devices are therefore much required in order to cram as much knowledge as possible, as fast as possible, into his swimming brain.

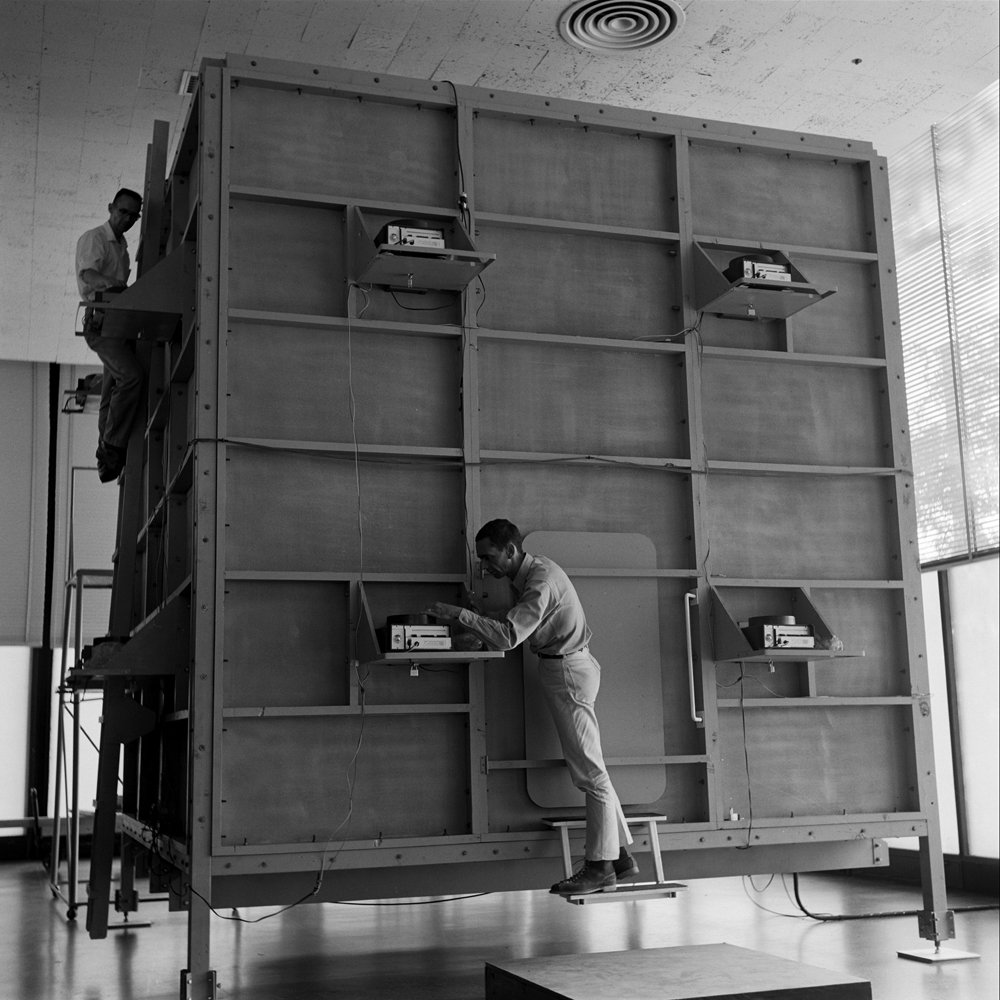

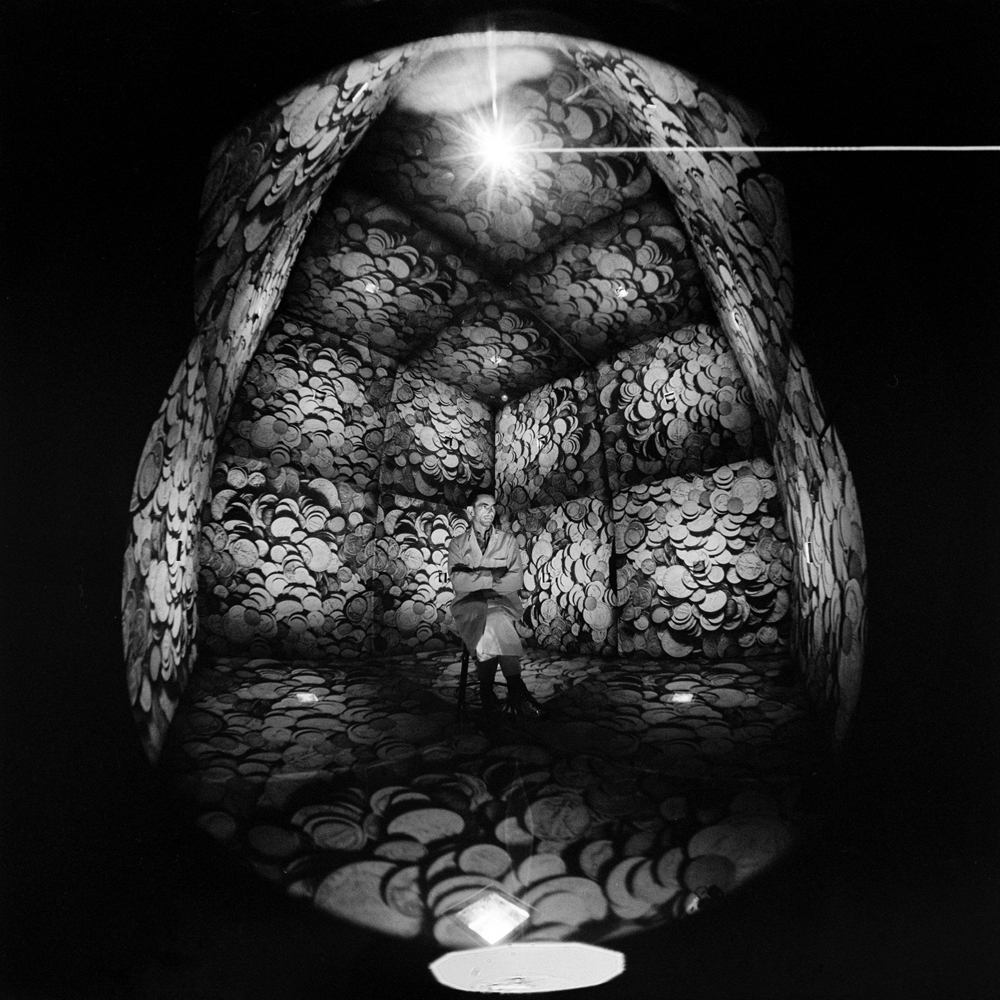

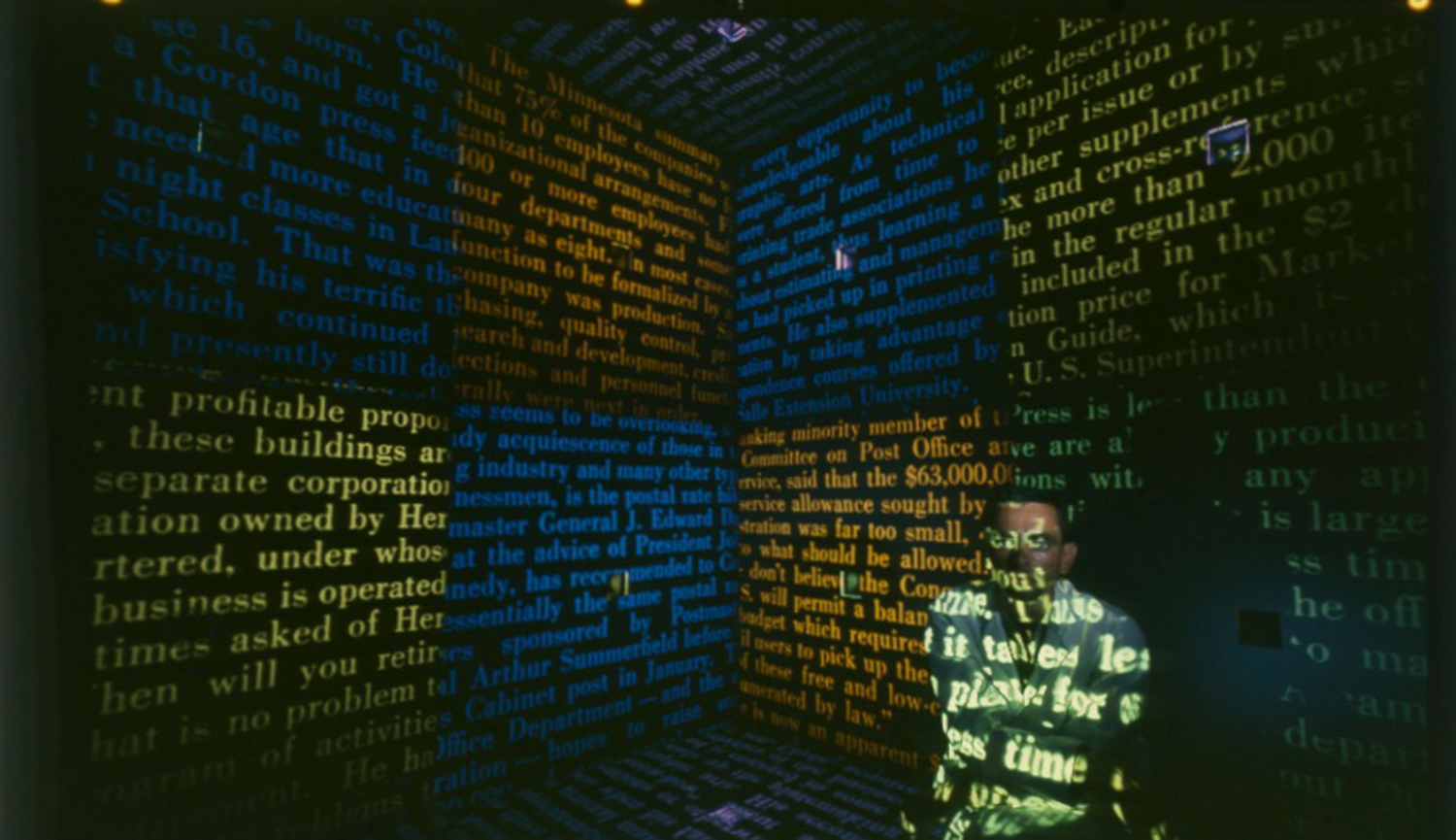

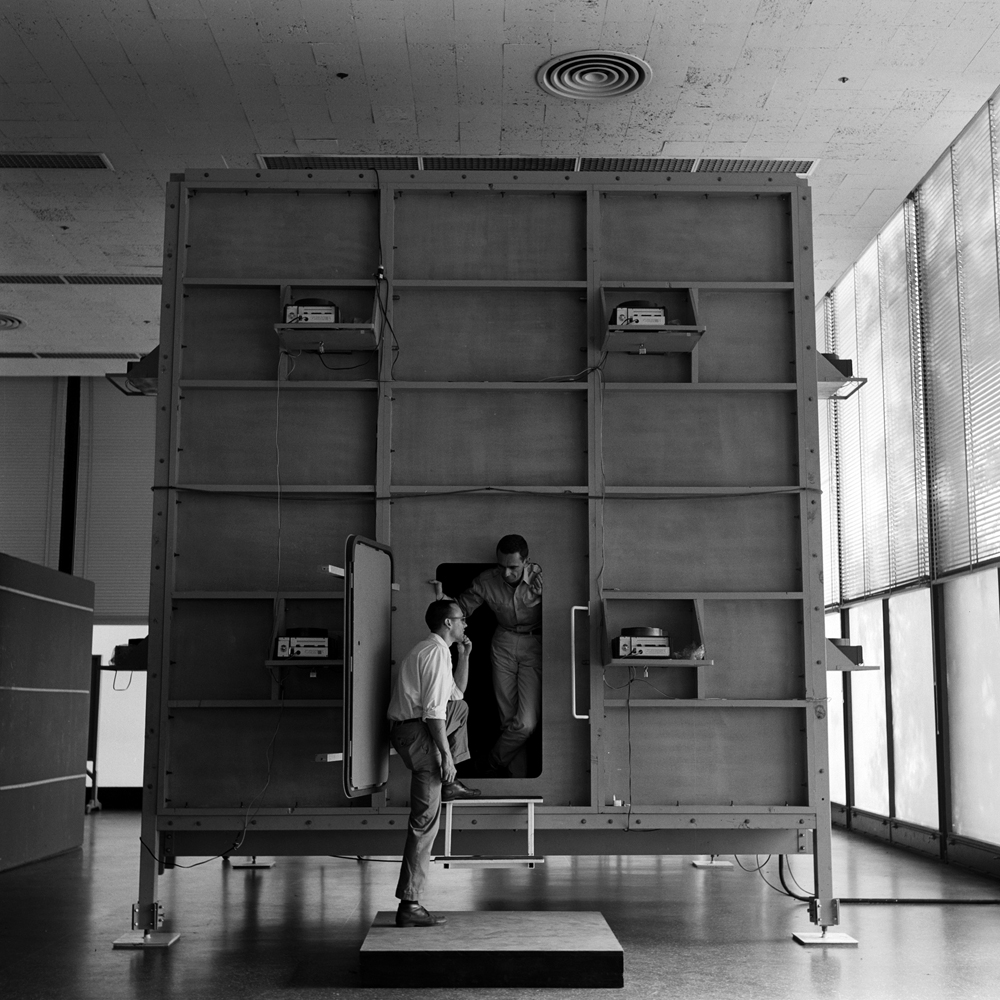

Out of the imagination of one specialist, 32-year-old designer Ken Isaacs of the Illinois Institute of Technology, has come a machine called a “knowledge box” that he hopes will help fill this need. Isaacs, peering from inside his weird cellular contrivance [see slide #4 in the gallery], believes that the traditional classroom environment is as ill-suited for learning as a ball park. Inside the knowledge box, alone and quiet, the student would see a rapid procession of thoughts and ideas projected on walls, ceilings and floor in a panoply of pictures, words and light patterns, leaving the mid to conclude for itself. It is a machine of visual impact that could depict, for example, a history of the Civil War in a single session, or just as easily give a waiting astronaut a lesson in celestial navigation.

The knowledge box was dismantled and went into storage not long after the article in LIFE came out. But Isaacs’ 12-foot, wood-framed cube—with its multiple slide projectors fire-hosing visual data at the occupant(s)—was reconstructed and put on display a few years back, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Sullivan Galleries. By all accounts, the “weird cellular contrivance” was as trippy and as impressive five decades later as it was when Isaacs first introduced it to an unprepared world in 1962.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com