It seemed like a simple task: buy some patio furniture for our old house in Delhi. I had moved there to become TIME’s bureau chief in the height of summer 2008, and the wide terrazzo veranda was the coolest spot on the property. After hours of searching Delhi’s furniture bazaars and high-end malls, my husband and I came back empty-handed. I sat down on the dusty marble, exhausted, and fantasized that someone might just deliver a table and chairs to the gate. Then, as if by magic, the bell rang. It was the jhuri-wala, the cane-furniture maker, making his rounds in the neighborhood. We invited him in, leafed through his binder of faded sample pictures and within a few days had a glass-topped round table and four chairs made of lacquered bamboo, cut, shaped and bound by hand.

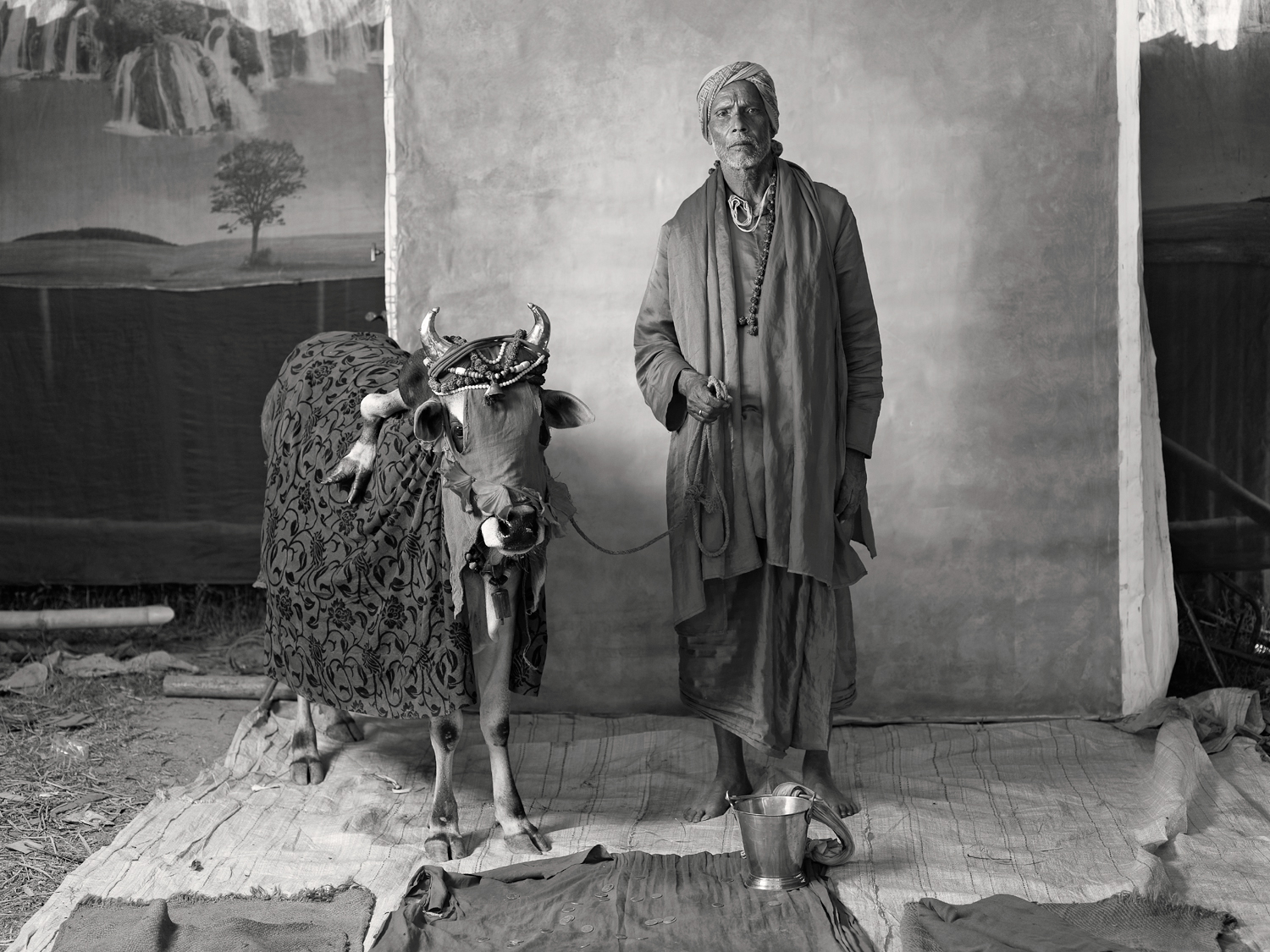

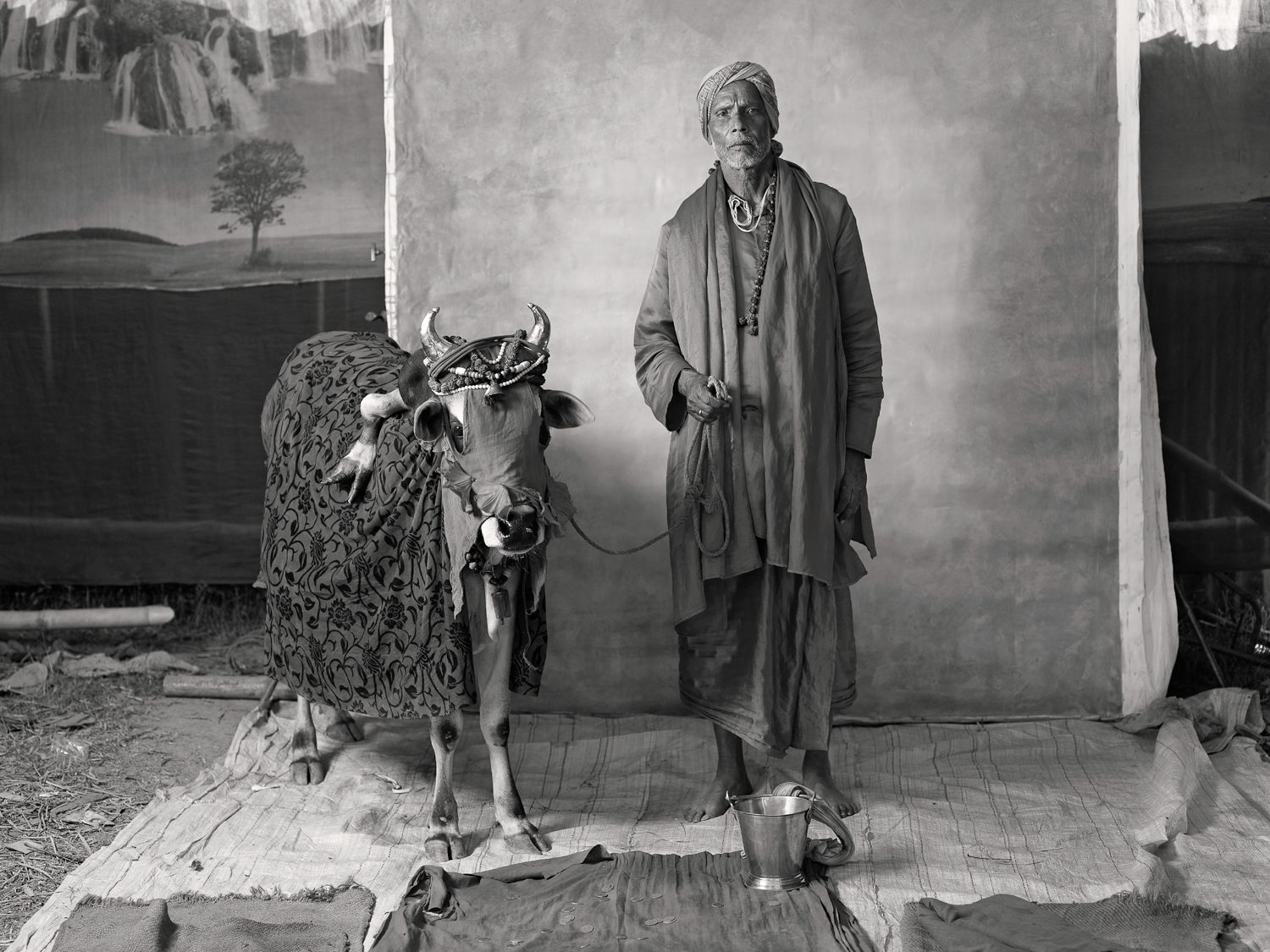

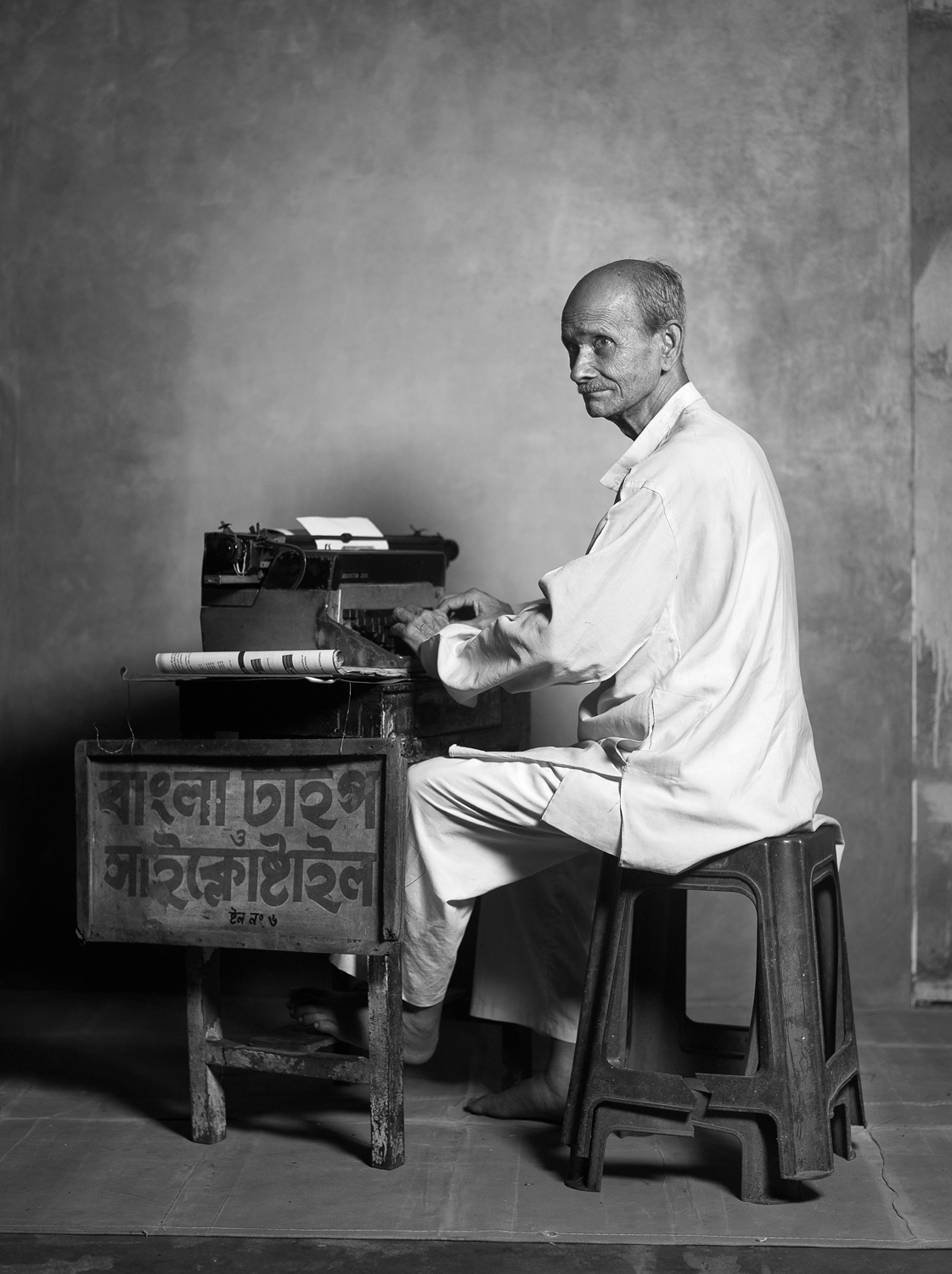

The jhuri-walas — and all the other craftsmen and tradespeople who populated the bylanes of our neighborhood — can make the housing colonies of India’s megacities feel like its villages. They are the subject of Supranav Dash’s photo essay Marginal Trades — among them are honey collectors and wood-cutters, blacksmiths and potters. Most inherited their professions, and the tools of their trades haven’t changed in generations. But they, too, are part of India’s economic transformation. Many families now prefer to buy plastic chairs rather than cane; some of these trades will soon die out. The wheat-grinder’s son manages a fast-food stall; a son of one of the washer-men is a chauffeur. “They never changed, they never updated themselves, and then suddenly you had this juncture when globalization is going to hit so bad, everything is changing,” Dash says.

Dash began this project as a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He turned to photography after years as a painter in Kolkata, his hometown, and as a photographer in Mumbai. Some of that early training is apparent; Dash used four different hand-painted backdrops. Under his thesis advisor, the painter Billy Sullivan, Dash studied the formal portraiture of the photographers Eugène Atget (Les Petits Métiers) and Irving Penn (Small Trades), who documented the trades and professions of London, Paris and New York in the 1950s. He researched Penn’s original platinum and palladium prints at the archives of the Museum of Modern Art and looked for representations of India’s trades and professions. The ethnographic work of John F. Watson and John W. Kaye (The People of India, 1868-75) informs Dash’s work but he did not want to replicate Watson and Kaye’s effort to render India’s multidimensional caste structure in a fixed taxonomy. “I did not want to follow that,” Dash says. “I wanted to inform people about what has happened and what is going to happen.”

Dash found his subjects in and around Kolkata. “In my summer and winter breaks I would go back to India, find a busy street and set up on a corner, make a makeshift studio, put two people in charge of the lights. Then, I would go hunting. Out of every 100 people, maybe 20 would accept.”

His biggest challenge was persuading them to leave their familiar surroundings. “They’re used to the concept of tourists coming in and taking snapshots in the street. But the moment you want to extract them and bring them to your own confined space, shoot, put them under lighting scenarios, they are, like, afraid,” Dash says. “They would say, like, Why don’t you photograph me right here where I’m standing? Why do you need to bring me and all my stuff back to your place? What if you beat me up and take all my stuff? Because the system does that to them. The system has abused them so much… A corrupted police officer and myself could be the same thing to them.”

Some of those who did agree to sit for portraits mentioned the Indian government’s massive new national ID program, which had been collecting biometric data at the same time that Dash was taking his portraits. “They would just mention that their photographs were also being taken [by the program], that the government wants data.” So far, more than 450 million people have been enrolled in India’s national ID program; the program’s chairman hopes to have 600 million Indians enrolled by 2014.

When my family and I left Delhi in 2012, we sold much of what we had acquired with the help of an auction agent, a freelance buyer and seller of household goods. The cane furniture went quickly; a few of the bindings had come loose, and the cracked glass top had been replaced, but it admirably withstood nearly four years of heat, dust storms and monsoons. I now live in Brooklyn, where artisanal trades and crafts are newly trendy. Every weekend, a bell rings; it’s the neighborhood knife-grinder making his rounds.

But I still often think of the jhuri-wala.

Supranav Dash is a fine-art, documentary and fashion photographer based in New York City.

Jyoti Thottam was formerly TIME’s South Asia Bureau Chief. Follow her on Twitter @JyotiThottam.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com