As journalists and photographers, we all fill with pride when we see our byline printed on the page. But never does the reader see the names of the fixers who make it all happen. Rarely do you read about the risks taken by local people who help us produce stories in incredibly dangerous places, then stay behind once we’re safely gone. And rarely do we thank these people who really are the core of war reportage and foreign correspondence.

Marrion P’Udongo is one of these names.

I first met Pastor Marrion when I was reporting on the causes of the conflict in eastern Congo for Human Rights Watch and TIME magazine. His smile greeted me in the café where I was sitting in Bunia and he asked if he could be of assistance. He was the pastor of a local church, he said. He also worked as a fixer with just about every journalist who passed through the region. And since I was a journalist, he offered to help me, too.

“My people need to be heard,” he said. “And your people need to understand what is going on. I can help them.” He then let out an infectious giggle that I’ve both come to love and fall victim to for the past seven years.

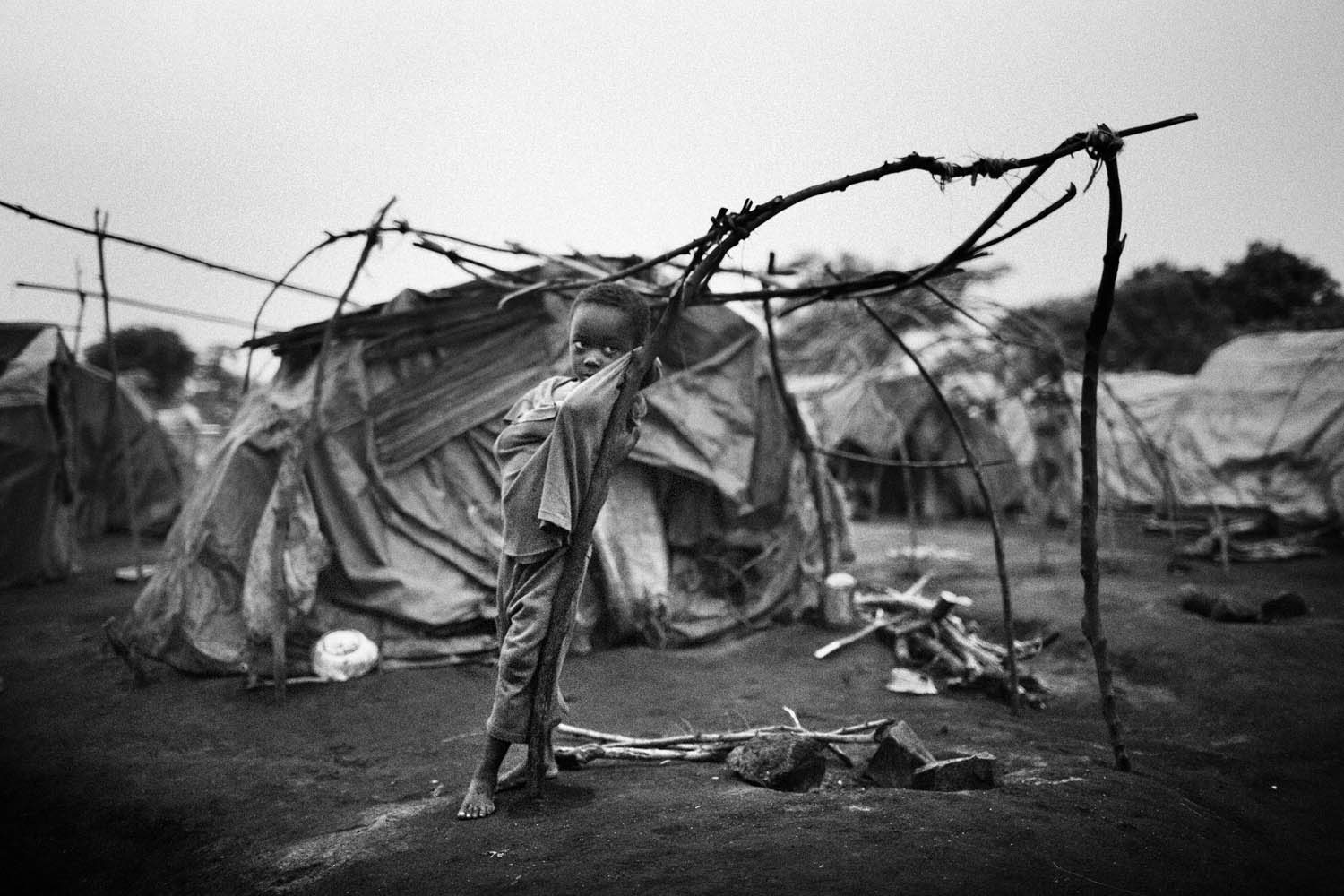

Pastor Marrion spent the next seven years guiding not only me, but many journalists, photographers, Hollywood film stars and human right activists through the dirty quagmire of eastern Congo. He spent years carefully walking us through displaced camps, dashing out of firefights, and into the heavy silence of homes of people who’d been raped and assaulted. And as a result, the world is more informed about this chronically underreported conflict.

He’s negotiated with rebel leaders so I could spend weeks in their camps. He has sat in the red mud of goldmines while I documented the exploitation of minerals that’s directly fueled this barbaric war. He has driven me down roads where no one else dared drive. And after crossing the frontlines one day outside Goma, he prayed as we huddled together in a sinkhole while drunken government troops fired at our heads.

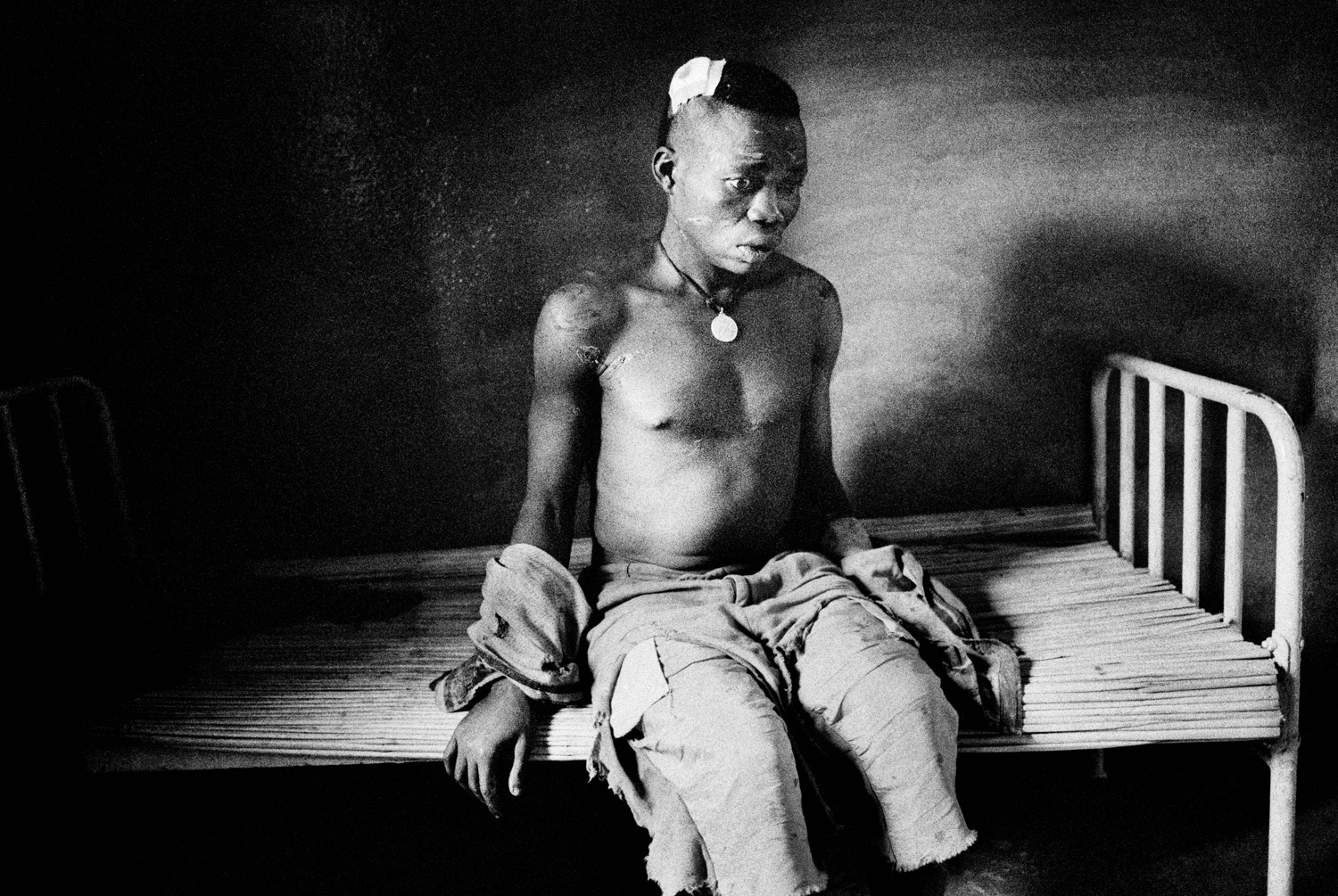

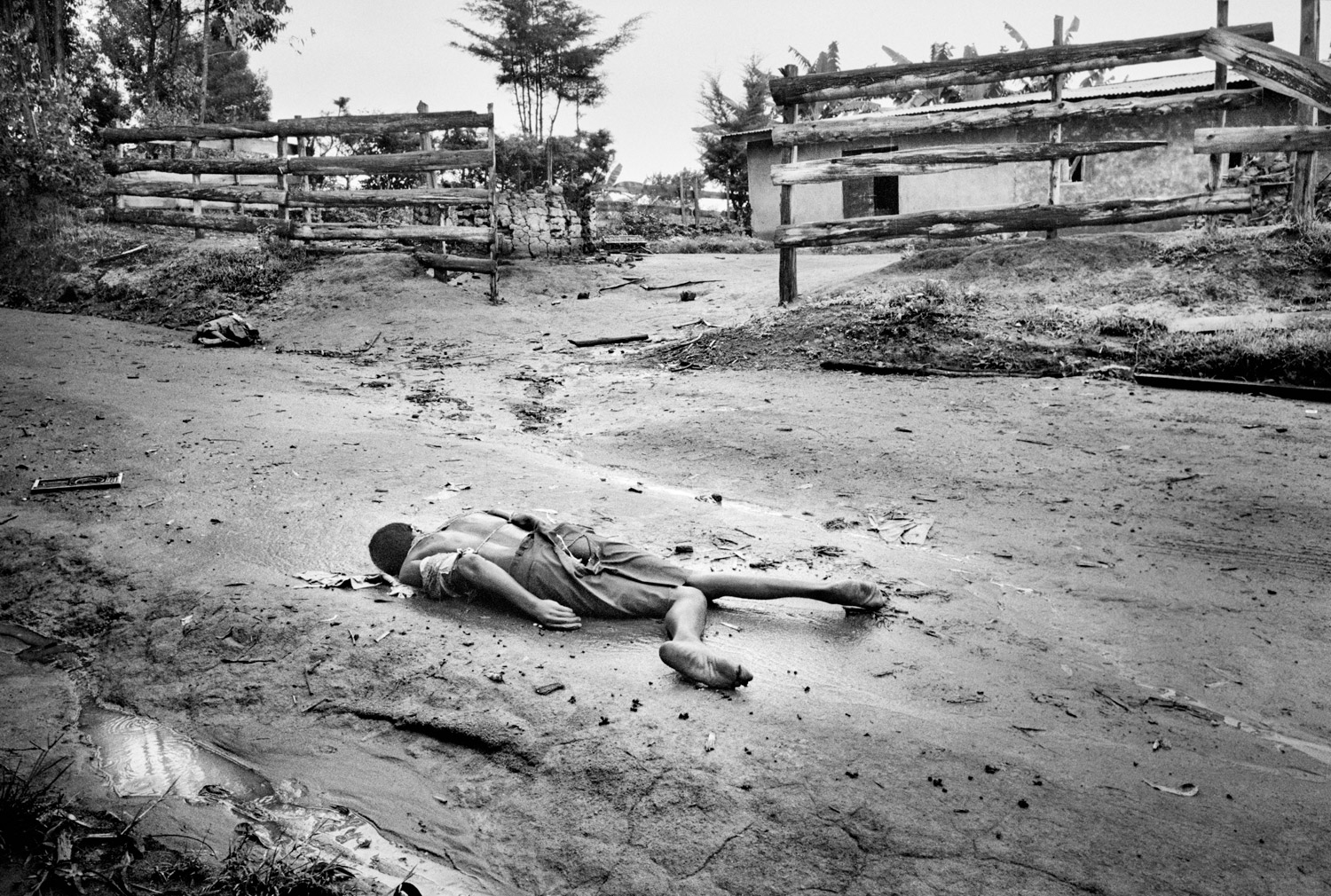

In a war that’s killed millions in Congo, Pastor Marrion has risked his life not only for journalists and photographers like myself, but also for his own people. In May 2003, the Pastor saved over 70 people from certain death when ethnic Lendu militia entered Bunia and began slaughtering their rival Hema in the streets. Pastor’s wife is a Hema, as are their children. When Lendu militia discovered them after several days hiding in Pastor’s living room, they stripped them naked and marched them to the road to be killed. Miraculously, one of the commanders had seen Marrion preach and begged the others to spare his life. The group was lead to safety in a nearby United Nations compound, just before militia returned and looted everything in his home.

And in the years afterward, he has picked children off the ground where they lay crying next to their dead mothers. Pastor Marrion takes them to the orphanage at St Kizito in Bunia, which he helps operate. For the few nuns who run St. Kizito, he negotiates with farmers to buy cows so the children can have regular milk. Much of the life-saving medicine at the orphanage was bought with money the Pastor earned from working with journalists.

Now the Pastor needs saving.

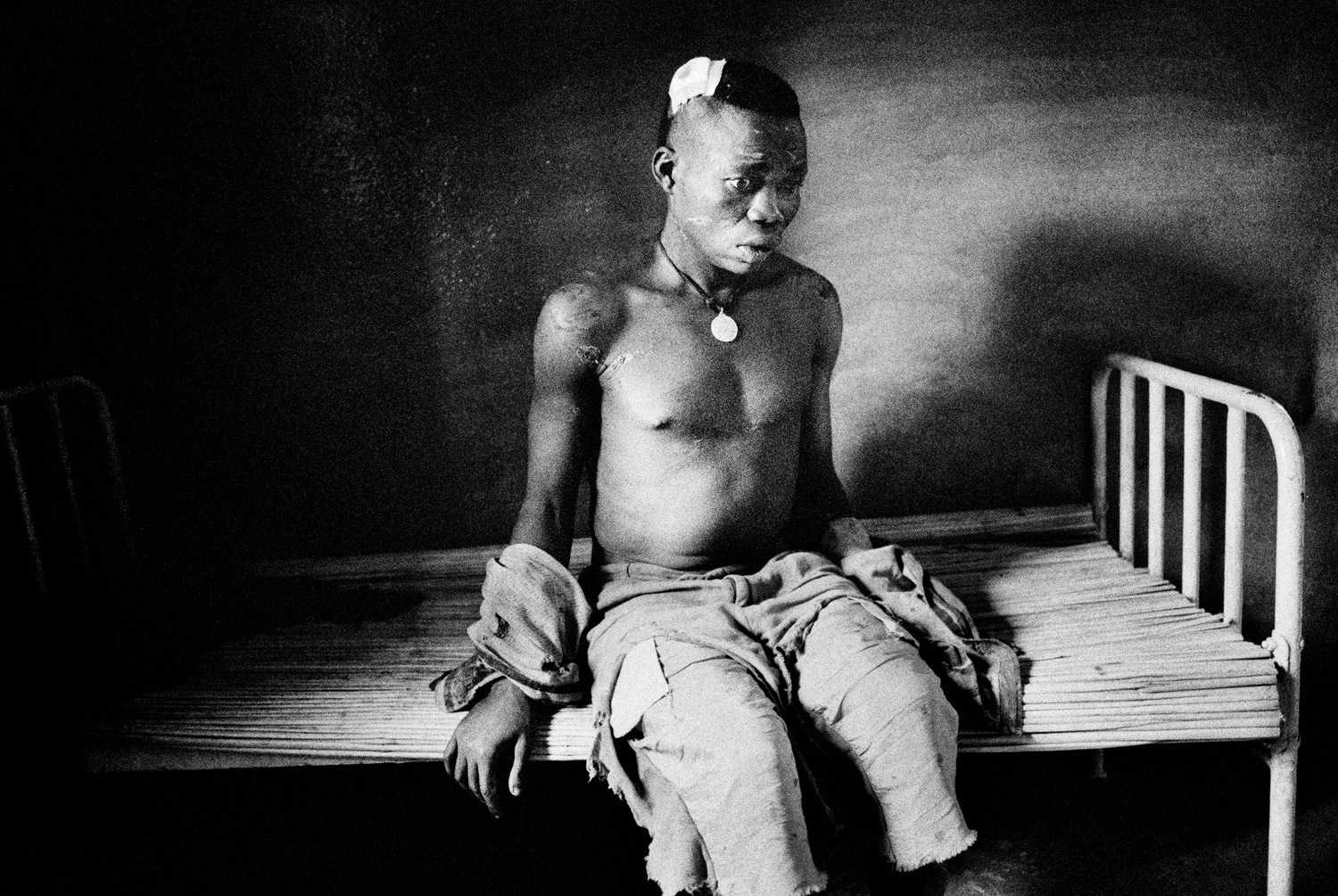

Last summer, he suffered severe renal failure and nearly died. Doctors said that in order to live, he’d need a kidney transplant – a costly procedure out of reach by most people in Africa, especially Congo. So a couple of colleagues and I decided to make it happen. For all the years of bravery and loyal friendship, it was the least we could do for him. The best news is Pastor Marrion found a kidney donor: his nephew. We managed to get him on dialysis, and then began raising money to pay for this transplant, which is now scheduled for later this month in Nairobi, Kenya. But we’re still about $10,000 short of saving his life, not to mention the thousands more that will be needed in the months that follow. Without this money, the man known as “the Oskar Schindler of Congo,” will never again lead us through the green hills of eastern Congo so the rest of the world can understand. The stories will go silent, and the torn community who so desperately need him will lose one of the best people they ever had.

To learn more about Pastor Marrion and to donate to the fund set up to help him, visit: http://www.indiegogo.com/The-Pastor-Marrion-Fund

Marcus Bleasdale, an award-winning photographer based in Oslo, is a member of the VII Photo Agency. Bleasdale has published two books, “One Hundred Years of Darkness” and “The Rape of a Nation“.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com