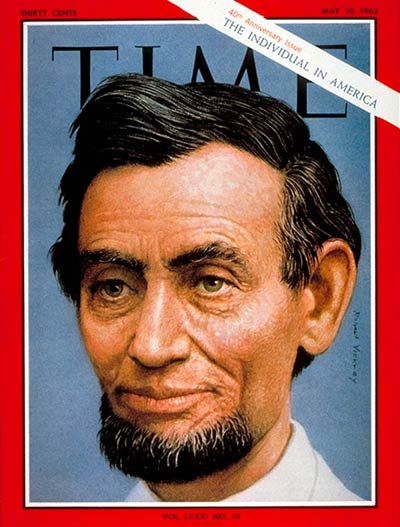

In May of 1963, when TIME devoted a six-page, 6,600-word essay to the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president — who was shot on April 14, 1865 — had been dead for nearly a century. The Emancipation Proclamation was a century old. The nation he led, TIME noted, would have been unrecognizable to him — the suburbs, the cars, the skyscrapers.

But that didn’t mean Lincoln had nothing to offer the America of the 1960s.

The central concern of the unbylined essay was the rise of the Organization Man, an idea that was at that point about a decade old. So-called after a 1956 book of that name, the Organization Man was — for better or worse — the American businessman devoted to his company and striving only for the comfortable conformity of post-war suburban life. The opposition of the Organization Man was the capital-I Individual, of which Lincoln was held up as a shining example.

Except, the essay explained, that Lincoln was also, in other ways, even as he was devoted to freedom and to change, the ultimate Organization Man. His company was the United States, and he was as loyal to it as any gold-watch-earning executive could be. He also knew that his loyalty would be worthless if he was the only one who felt it.

The lesson of Lincoln, then, was not that Individualism — though one of American culture’s most treasured values — was best. His lesson was that life was not really about the collective versus the individual. Rather, one could not exist without the other:

Abraham Lincoln’s life connects colonial America with modern America; Jefferson died when Lincoln was 17, Woodrow Wilson was eight when Lincoln died. While America was fighting its war, the greater battle of the modern world was already joined.

John Stuart Mill had finished his essay “On Liberty,” in which he expressed the horror with which 19th century liberalism regarded the state, and enunciated the magnificent principle that “if all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion,” mankind would still not be justified in silencing him. Yet at that very time, Karl Marx was writing Das Kapital, striking back at liberal individualism in the name of mankind. For the industrial worker, argued Marx, had been “reduced to a mere fragment of a man, mentally and physically dehumanized,” and only collective action, state action, could redress his wrongs.

Thus began the long Marxist offensive that eventually led to Communism and fascism. Just as the U.S. had succeeded in tempering and transforming the forces that became the French Revolution, it tempered and transformed the Socialist Revolution. America had its age of ruggedly individualistic businessmen, when popularizers turned Darwin’s theory of natural selection into a doctrine of economic predestination, according to which the damnation of the weak was a law of nature. But out of this era grew the sometimes uneasy partnership between business and government that in effect built a capitalist welfare state and an almost universal middle class society.

This is the central fact about the individual today. The life now led by Americans (and to a great extent by Europeans) was made possible only through industrial, and organized, civilization. Hence what is often denounced as regimentation of the individual is the price paid for giving virtually every individual a chance to live a wider, longer, richer life.

Read the full 1963 essay, here in the TIME Vault: Lincoln and Modern America

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com