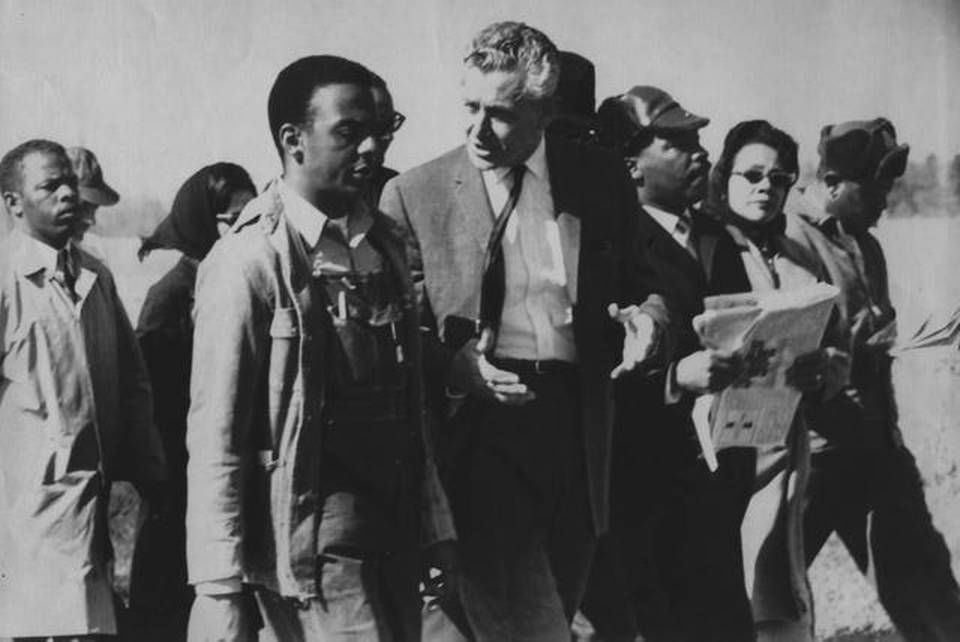

A photograph has the power to change minds and open them, reveal truths and distort them. It also has the power to lose elections, as this photograph of LeRoy Collins marching from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery with civil rights leaders demonstrated when Collins ran for U.S. Senate in 1968.

The real story, though, is not only in the consequences the photo engendered after it was taken, but also in the events that led Collins to the front of the march on that early spring day, sandwiched between Andrew Young and Martin Luther King Jr.

Two weeks before the photograph was made, the brutal events of “Bloody Sunday” had horrified almost anyone with access to a television or newspaper: King and many others had attempted a protest march from Selma to Montgomery, but they had been turned back with violence at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. President Johnson hoped to stave off the violence and media attention a second attempt at reaching the state capital would surely yield. But, despite a pending restraining order placed on the march by a federal judge, King planned to move forward. He was going to try again just a few days later, on March 9, 1965.

So Johnson dispatched Collins, a former Florida governor who had been appointed to direct the newly formed Community Relations Service (CRS), to keep an already escalating situation from erupting uncontrollably. CRS, which had been established under the 1964 Civil Rights Act as the peacemaking arm of the Department of Justice, was charged with mediating community conflicts rooted in race, religion and other human differences. The tensions in Selma fit squarely in the agency’s wheelhouse.

Collins, who had never met King before that day, attempted to broker a deal in which King would stop the march on the bridge and then turn around, in exchange for which Alabama State Trooper Colonel Al Lingo would agree not to use force. Both King and Lingo offered tepid agreement, and when the pivotal moment arrived, both men kept their word. King led a brief prayer and song and instructed surprised marchers to about-face, a move that caused the day to later be nicknamed “Turnaround Tuesday.”

The halt surprised the press as much as it did the marchers. According an account of the day’s events by Collins’ biographer, Martin Dyckman, the CRS’ arrival in Selma had gone unannounced, as the agency’s establishing law required it to operate without publicity.

Collins remained in Alabama to negotiate with city and state officials in Montgomery, as the date neared for a third attempt to complete the walk from Selma. That walk, which began March 21, was ultimately successful: King and his followers reached the state capital on March 25, 1965, a half-century ago today.

It was during the second day of marching that Collins reached the head of the line to discuss plans for the coming days with King, Young and other leaders. The photograph that captured their brief conference would appear on the front pages of newspapers across Florida the following day.

When Collins was nominated by the Democratic Party to fill a vacant U.S. Senate seat in 1968, the photograph reemerged, not as a demonstration of the CRS’ success in mediating the marches, but as a campaign tactic by Collins’ Republican opponent. Many Florida voters, not realizing his role as a mediator, perceived the photo as an image of Collins helping to lead the march. In a southern state that was far from progressive on civil-rights issues, this perception sounded the death knell for Collins’ chances in the election—and his career in politics.

But for Collins, the career he traded for peace in Selma—or at least as much peace as one agency could hope to achieve—was a worthy barter. His daughter Jane Aurell recently told the Miami Herald that Collins never regretted the work he did in Selma: “He would never have undone what he did.”

Read TIME’s 1955 cover story on LeRoy Collins’ Florida governorship, here in the TIME Vault: Florida: A Place in the Sun

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com