In the midst of the contentious debate between anti-vaxxers and those who side with mainstream science, it can be hard to imagine a time when Americans almost universally embraced vaccination.

That time was the 1950s, when the very real, utterly devastating effects of polio overshadowed any hypothetical questions of vaccine safety. In 1952, the worst polio outbreak in American history infected 58,000 people, killing more than 3,000 and paralyzing 21,000 — the majority of them children. As TIME reported, “Parents were haunted by the stories of children stricken suddenly by the telltale cramps and fever. Public swimming pools were deserted for fear of contagion. And year after year polio delivered thousands of people into hospitals and wheelchairs, or into the nightmarish canisters called iron lungs.”

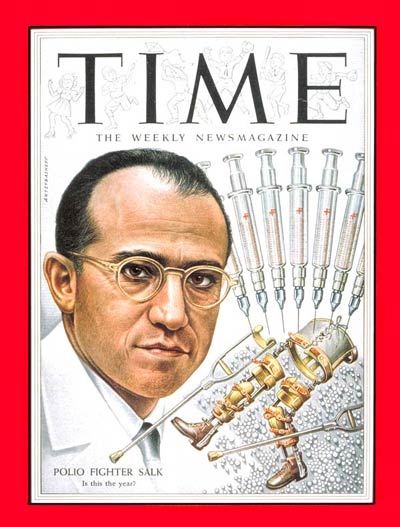

When Dr. Jonas Salk’s vaccine debuted its first mass inoculation against polio on this day, Feb. 23, in 1954, the only fear most parents felt was that it wouldn’t become widely available fast enough to save their kids.

Children from the Arsenal Elementary School in Pittsburgh, where Salk ran his research lab, took part in the first “field test” of the new vaccine, although Salk had already tried it on volunteers — starting with himself, his wife, and their children — who’d successfully produced polio antibodies without getting sick. By June, nearly two million schoolchildren in 44 states had been inoculated, and a year later the vaccine was officially licensed.

During its initial testing, the most salient safety question about Salk’s vaccine centered on the potential danger of injecting humans with monkey tissue. To make his vaccine, Salk’s team harvested kidneys from live monkeys and injected them with live polio virus, which quickly multiplied in the kidney cells. Then the team used formaldehyde to kill the virus before injecting it into humans.

But the traces of monkey kidney present in each dose of the vaccine were so minute that they posed no health risks, as Salk told the New York Times.

Instead, the greatest safety threat came not from monkeys but from human error: One of the labs licensed to produce the vaccine accidentally contaminated a batch with live polio virus in 1955. That batch killed five people and paralyzed 51.

With stricter oversight, however, the vaccine continued to be the lifesaver it was initially hailed as. Within the first few years, it cut polio cases in the U.S. by half. By 1962, the number of new cases had dropped to fewer than 1,000. And by the time of Salk’s death at age 80, 20 years ago, polio was already virtually extinct in the U.S. and dwindling worldwide.

Read the 1954 cover story about the polio vaccine, here in the TIME archives: Closing in on Polio

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com