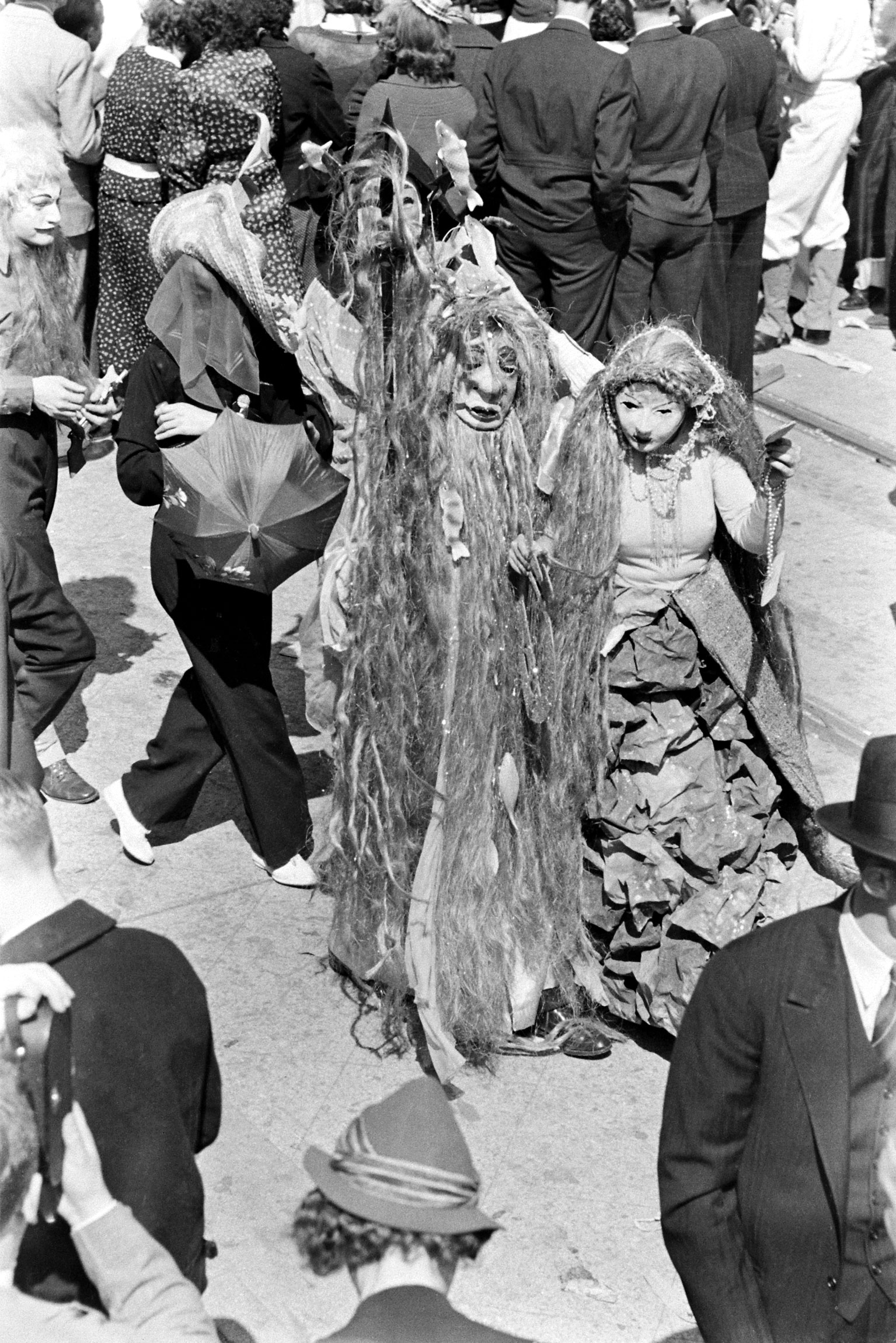

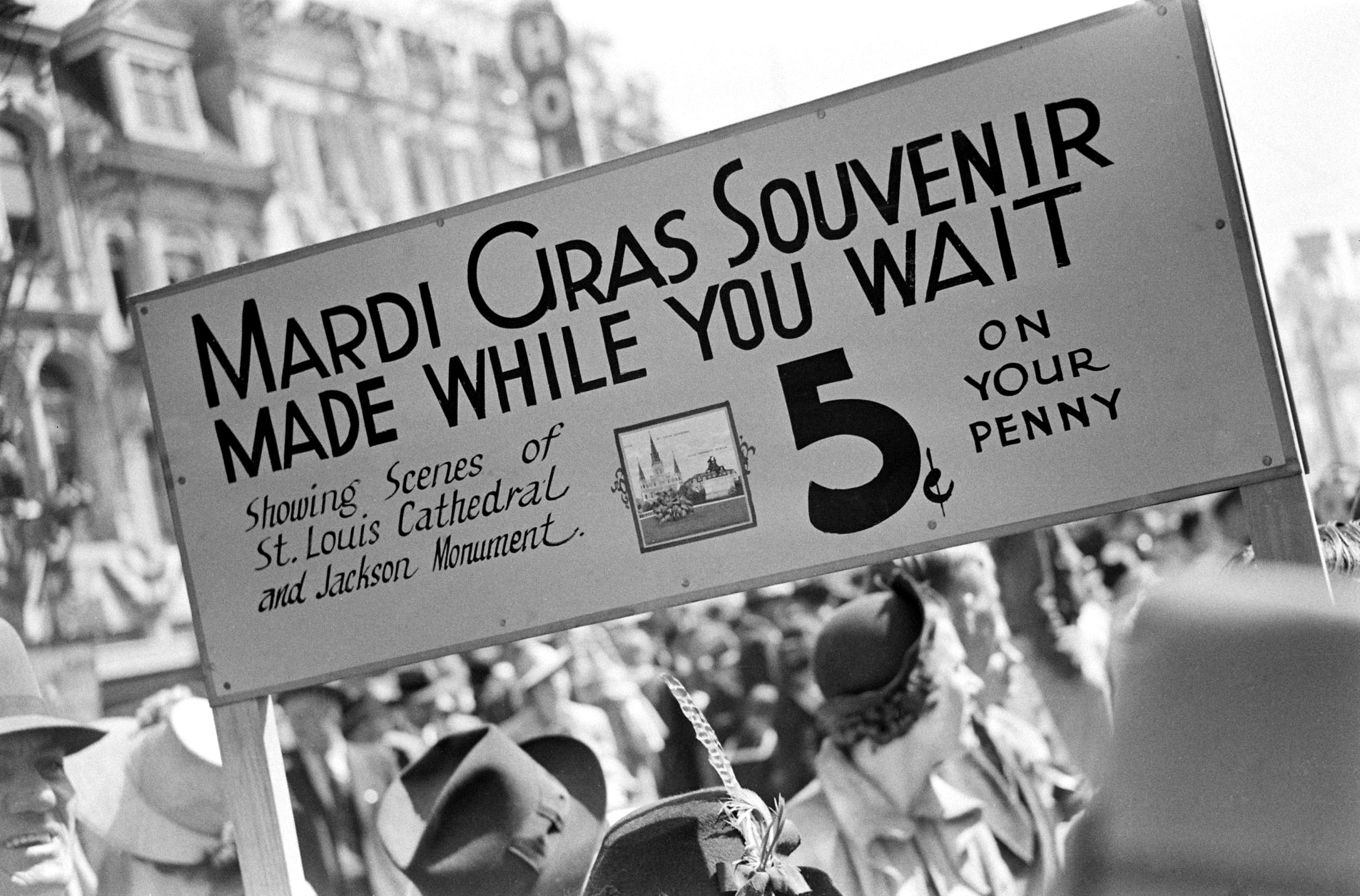

These days, Mardi Gras in New Orleans — which falls on Feb. 17 this year — is a party for all. But, not that long ago, Mardi Gras celebrations were more exclusive affairs.

As TIME reported in the Feb. 9, 1948, issue, balls and “krewes” were for the city’s elites only, and that situation lasted for decades after the first Mardi Gras parade was held in the 1850s. In the 20th century, however, the celebration expanded:

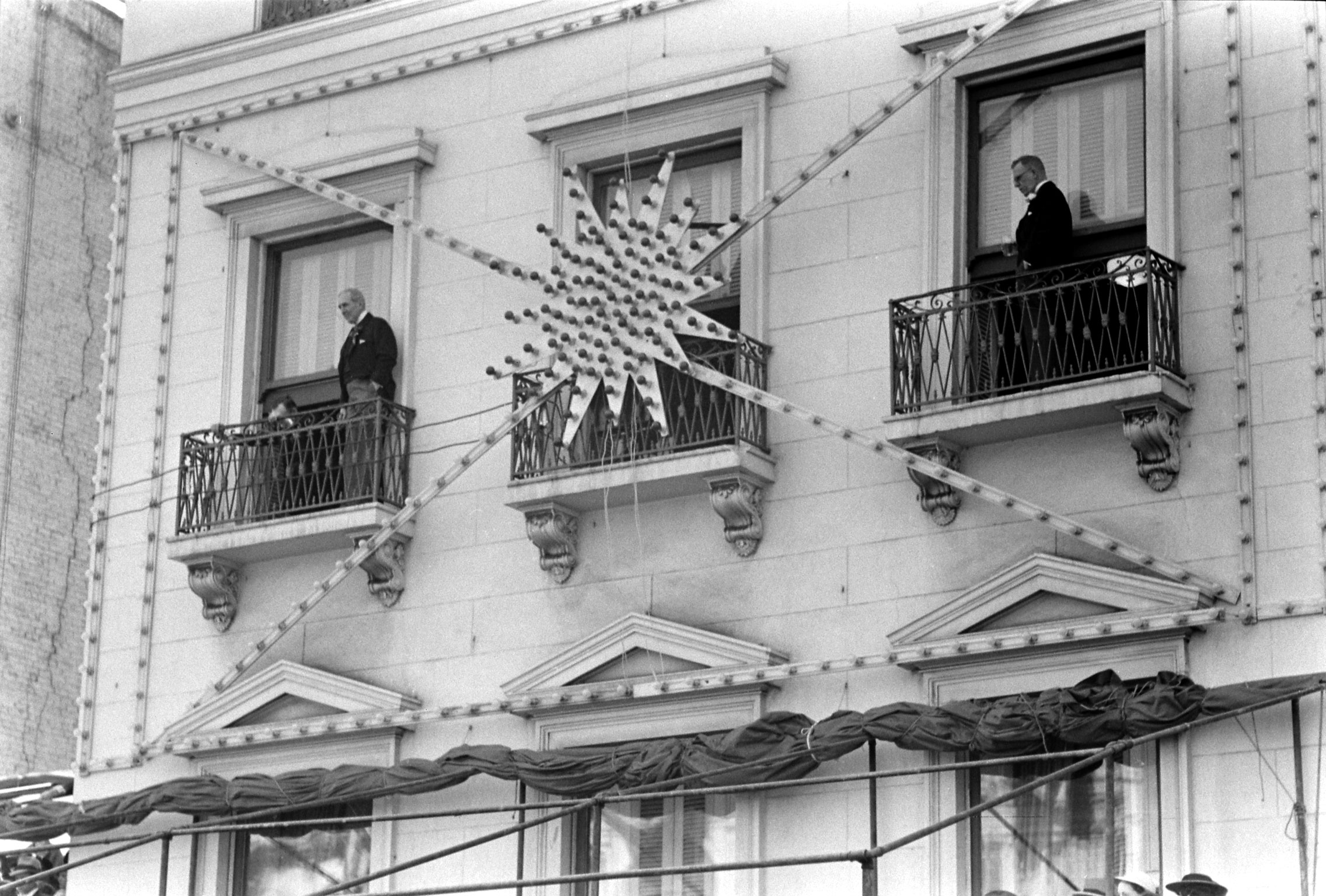

For half a century, New Orleans’ fantastic Mardi Gras balls were strictly for the upper crust. Nobody without money, blue blood, or both gained membership in the secret men’s clubs or “krewes” which staged them. Before 1900 there were only five clubs: Comus, Momus, Twelfth Night, Rex and Proteus. They culled guest lists with pernickety care, asked only the fairest of debutantes to serve as carnival queens. But times changed. The socially ambitious began forming their own krewes.

In 1928 New Orleans had 16 Mardi Gras balls. In 1946 there were 36. This year, a record-breaking total of 49 are being held. Last week, with Carnival Day (Shrove Tuesday) fast approaching, New Orleans’ social whirl had assumed the proportions of a maelstrom.

By the 1940s, there were krewe options galore. “Italian krewes, Irish krewes, German krewes… krewes for college men, businessmen, professional men,” TIME wrote. “To the horror of New Orleans’ old guard, there are even krewes for women.”

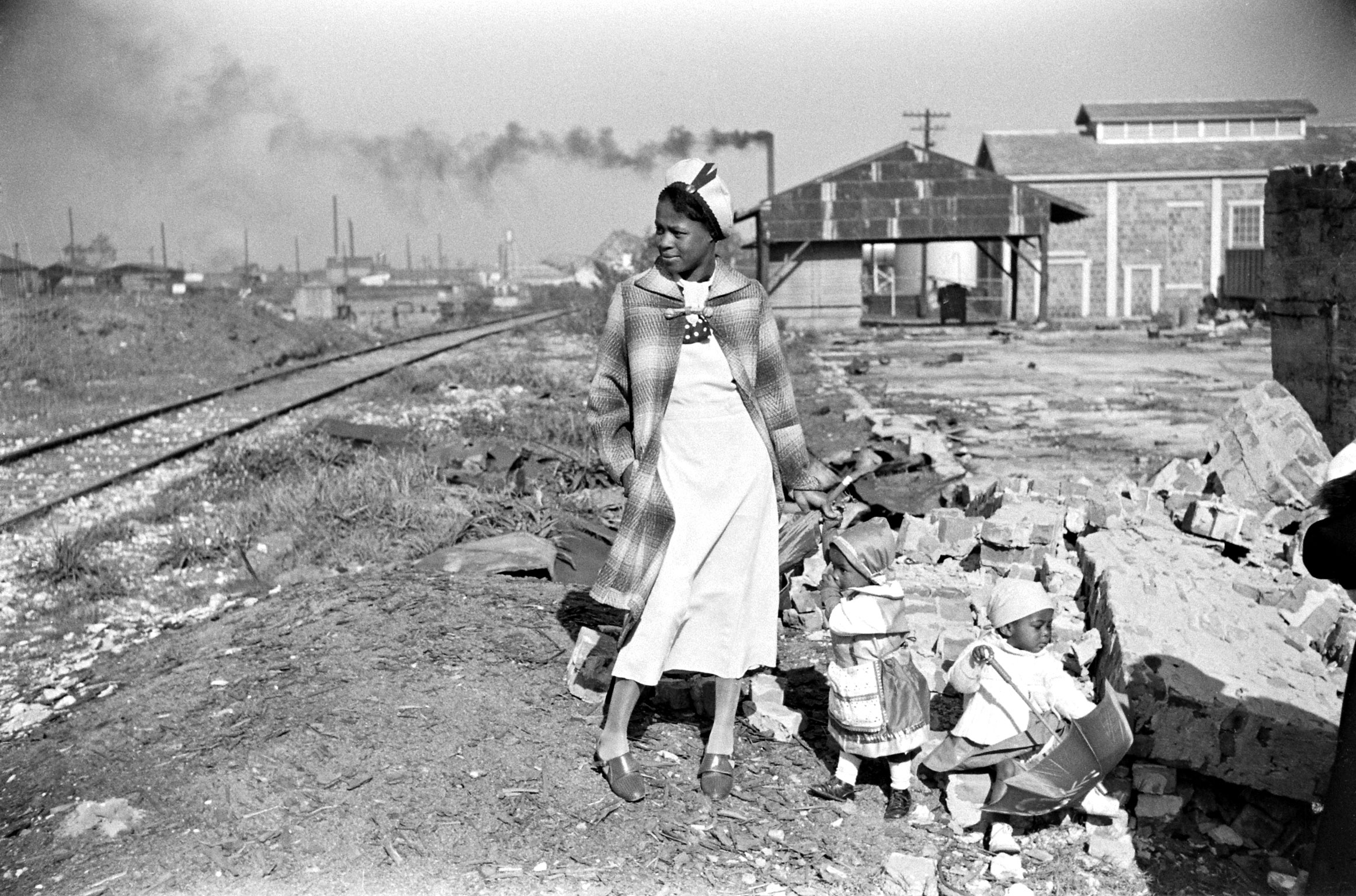

But that didn’t mean Mardi Gras was an all-inclusive celebration. The krewes may have multiplied, but they were still separated along racial and gender lines.

As recently as 1991, the relative exclusivity of the Mardi Gras krewes was a source of controversy in New Orleans. That December, the city council voted to require the krewes to integrate by 1994, or else lose the right to hold parades. (The krewes are private clubs, but the city controls the streets.) As TIME reported, the reaction was big but not exactly easy:

The 60 carnival groups, known as krewes, assailed the measure as a ”tragic mistake” that could drive the festival out of New Orleans. Two of the most prestigious groups, the Mistick Krewe of Comus and the Knights of Momus — both all white, all male — have announced that they will not parade, citing government intrusion. Other krewes have threatened to cancel their parades or relocate them in future years unless the ordinance is radically altered.

At the time, the city was majority African-American, but polls showed that even most black voters did not want to integrate the krewes. At the time, many who opposed the change argued that the krewes’ make-ups were a matter of tradition, not discrimination. However, as the article noted, the barriers were not just racial, but also along religion, sexual and ethnic lines — and krewe membership was important for a lot more than a parade, as it went hand-in-hand with business, social and political networks. Though the measure was weakened — single-sex krewes were allowed, for example — it was enough to keep some of the oldest and most stubborn krewes from ever parading again, as the number and size of the integrated krewes expanded.

Two decades later, there are dozens of krewes that organize balls and parade floats. And, as the Times-Picayune‘s James Gill observed recently, it’s easy to tell that the krewes have modernized and opened up: where they were once the domain of money and blue blood, these days membership applications to many krewes are available to anyone with an Internet connection.

Mardi Gras: Rare Vintage Photos From America's Most Famous Party

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com