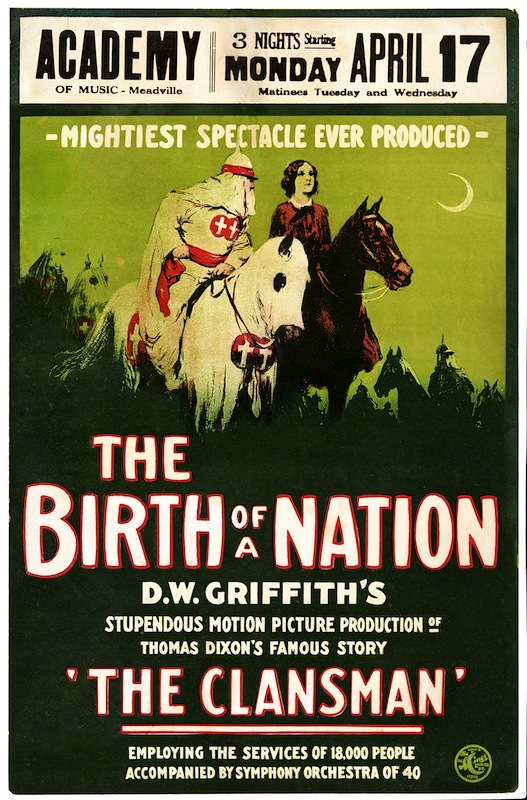

The Birth of a Nation, by all accounts the first American blockbuster, the first historical epic, the first Hollywood film to resemble what movies are like today, premiered in Los Angeles exactly 100 years ago on Sunday. But the centennial won’t be celebratory. It will likely be awkward, sobering even — because in director D.W. Griffith’s 12-reel Civil War saga, the Ku Klux Klan members are the glorious heroes.

Since its premiere on Feb. 8, 1915, the film has been at once wildly popular and widely condemned. It inspired the revival of the KKK but also galvanized what was then a nascent NAACP into action. It helped define what cinema means for American audiences. It was the first film ever shown inside the White House.

After 100 years, it has left a complicated, powerful legacy, but a legacy of what, exactly?

“Excuses are sometimes made by scholars of film for the content, but I don’t think that for the last ten to 15 years there has been any doubt that this is an unequivocally, viciously racist film,” says Paul McEwan, Associate Professor of Media and Communications at Muhlenberg College. McEwan has been studying and writing about the history of Birth of a Nation for 12 years. “I mean, this film makes Gone With the Wind look very progressive.”

Griffith claimed to be filming history, but Birth of a Nation, based on the novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, features a stunning revision of Reconstruction. White actors in blackface portray members of a barbaric, sex-crazed militia of freedmen that terrorizes and disenfranchises cowering whites. Black men overtake South Carolina’s judicial system and legislature, swigging whiskey and eating fried chicken on the floor of the State House. After the blackface character Gus attempts to rape a white woman, the protagonists don their hoods and apprehend him, lynching him after their version of a fair trial. The film is ostensibly about white national reconciliation at the expense of emancipated black Americans. A title card punctuates the action toward the end of the silent film to declare, “The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright.”

Despite its objectionable content, the film remains an essential part of the discussion about American cinema because of Griffith’s pioneering technical innovations. Things that today are completely taken for granted — like close-ups, fade-outs and even varying camera angles — originated with Birth of a Nation‘s director and crew.

Because of its landmark cinematic achievements, dialogue surrounding the film has been fraught with debate pitting its artistic value against its dangerous racial politics. Famously, filmmaker Spike Lee has described seeing the film in a class as a first-year student. While professors were eager to applaud all the innovations of the film, lauding Griffith as “the father of cinema,” they ignored its implications as a racist epic. Lee responded with one of his first-year projects, called The Answer, about a black screenwriter drafted to write a Birth of a Nation remake.

In the 1970s, a journalist in Connecticut named Dick Lehr infiltrated a recruitment meeting of the KKK. There, Grand Wizard David Duke treated attendees to a screening of the film. Lehr, who had studied the film in college, said exposure to the film “in the real world” made him start considering the consequences of its content. Last November he published Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Filmmaker and a Crusading Editor Reignited America’s Civil War. The book chronicles the backlash against the film in African American communities, particularly protests in Boston that were led by Monroe Trotter.

“In 1915, black leaders were appalled and outraged,” Lehr tells TIME. The film helped galvanize protests by thousands of African Americans, which Lehr characterizes as powerful foreshadowing of the Civil Rights movement.

President Woodrow Wilson cast Trotter and his protestors out of the White House after Trotter, a Harvard-educated newspaper editor, confronted him. “Wilson is a very well documented racist,” Lehr says. “He was very paternalistic, and Trotter became persona non grata because Wilson just thought ‘how dare you speak to me this way.'”

A few months later, Wilson hosted Griffith and novelist Dixon, a college friend of Wilson’s, for a screening of Birth of a Nation, the second film ever shown on the grounds of the White House and the first ever inside. Wilson lauded the film, famously commenting that it was “like writing history with lightning.” Excerpts from Wilson’s History of the American People appeared in the film to justify the portrayal of the Reconstruction-era South. The film quotes, “The policy of the congressional leaders wrought…a veritable overthrow of civilization in the South…in their determination to ‘put the white South under the heel of the black South.'”

It’s obvious, then, that the film has managed to sustain dual meanings for a whole century: its cinematic advances are still relevant, but its racism is still shocking. But, says Muhlenberg’s McEwan, there’s another piece of that legacy — and it’s one that’s a lot harder to see.

“For a long time the question was just, is it racist or is it art? Well, it’s both, and that’s more complicated,” McEwan says. “For American audiences, I think the legacy of the film is a cautionary tale. Especially on the centennial, you have to look 100 years into our future, and think about what we do, what our Birth of a Nation is going to be once that eye of judgement is turned on us.”

But perhaps there’s reason to hope that our own version, the movie we’ll be shocked at in 2115, won’t be quite so shameful. After all, in thinking about the centennial, Lehr says he noticed some hopeful irony: The first movie to screen in the White House was Birth of a Nation, but one of the most recent was Selma.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com