Fifteen years after the U.S. declared the measles eliminated, a growing outbreak has many up in arms about the risks posed to public health by parents who choose not to vaccinate their children. Fifty years ago, the debate centered not on whether to vaccinate babies, but whether a pregnant woman infected with the virus should be able to decide whether to have the baby in the first place.

The year was 1965. A growing movement calling for legalized abortion would declare victory with Roe v. Wade eight years later, but until then, women seeking abortions would either be denied or undergo the procedure in secrecy. A small number of doctors, however, chose to deliberately defy the law and perform abortions on women whose fetuses had been exposed to the German measles, also known as rubella.

The year before, an outbreak of rubella had spread across the East Coast, Midwest and South. When it reached California during the spring of 1965, LIFE Magazine assigned reporter Bob Liang and photographer Co Rentmeester to investigate reports that “reputable doctors in reputable hospitals” were performing abortions on women infected with rubella during the early stages of their pregnancies.

After being turned away from every obstetrician in the Los Angeles phone book, Liang found Keith Russell, head of the California Obstetricians Society and a doctor with an interest in reforming abortion laws. Russell led Liang to the hospital where he would encounter Dolores Stonebreaker, a pregnant woman who had contracted rubella from her 12-year-old son.

After weighing the advice of her husband and doctor — and the vague guidance of her Roman Catholic priest, who would later reproach her for murder — Stonebreaker was preparing to terminate her pregnancy on the 50-50 chance that her baby would be born with “mental retardation, heart defects, blindness, deafness, disease of the bone and blood abnormalities.”

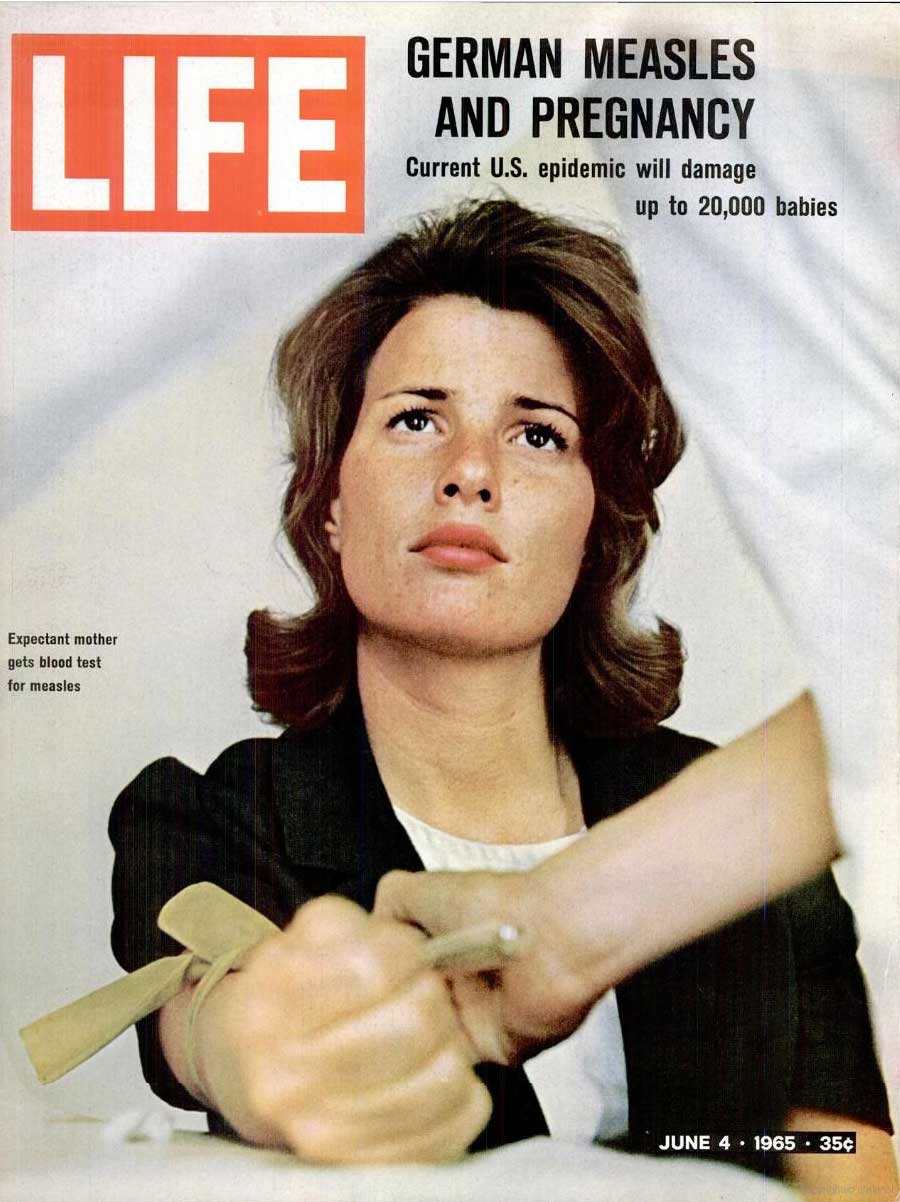

Stonebreaker’s infection had manifested in a rash, but many pregnant women exhibited no symptoms, leading to a majority of “German measles babies” — 9 out of 10 — born to mothers who had been unaware of their infections. To address this, doctors developed a blood test for pregnant women, who could find out whether they had been infected even if a subsequent decision to terminate the pregnancy could only be made illegally.

A rubella vaccine was only five years away, and the combined measles, mumps, rubella vaccine would emerge in the early 1970s. But the questions the virus raised with regard to abortion added fuel to a fire already stoked by cases like that of Sherri Finkbine, who traveled to Sweden in 1962 to terminate a pregnancy after learning that pills she had been taking contained Thalidomide. Although staunch opponents, including many Catholic clerics, argued that terminating a pregnancy with a chance of birth defects could “doom a possibly perfect baby in the process,” public sympathy for some women seeking abortions — like Stonebreaker and Finkbine — was also spreading.

By 1968, four states had passed laws allowing women to terminate a pregnancy if, as TIME reported then, “the child is likely to be born defective, as is commonly the case if the mother has had German measles (rubella) within the first three months of pregnancy.” Russell, the doctor who led Liang and Rentmeester to their story, would become a leader among others in the medical community who believed in therapeutic abortion and, more broadly, in a woman’s right to make those decisions privately with her doctor.

When Liang reported back to LIFE’s editor in chief about the assignment, he lauded Stonebreaker’s doctor — the one Russell had led him to — as “a brave man.” Despite the risks to his career and reputation, “he dared to stick his neck out for something he believed in.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com