Boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love. Boy and girl get married, buy a house and have (on average) 2.2 children. This may have been a common story for heterosexual couples in America in the 1950s, but when LIFE dispatched John Dominis to capture love and marriage in post-war Japan, he found a landscape undergoing a significant transformation.

Before the war, most marriages in Japan were arranged by the bride’s and groom’s parents. Men and women rarely spent much time together prior to the wedding, let alone took part in anything that might qualify as “dating.” But during the Allied occupation of Japan—from the end of World War II until 1952—the ubiquity of the American soldier’s courtship rituals jump-started the Westernization of love and marriage in Japan.

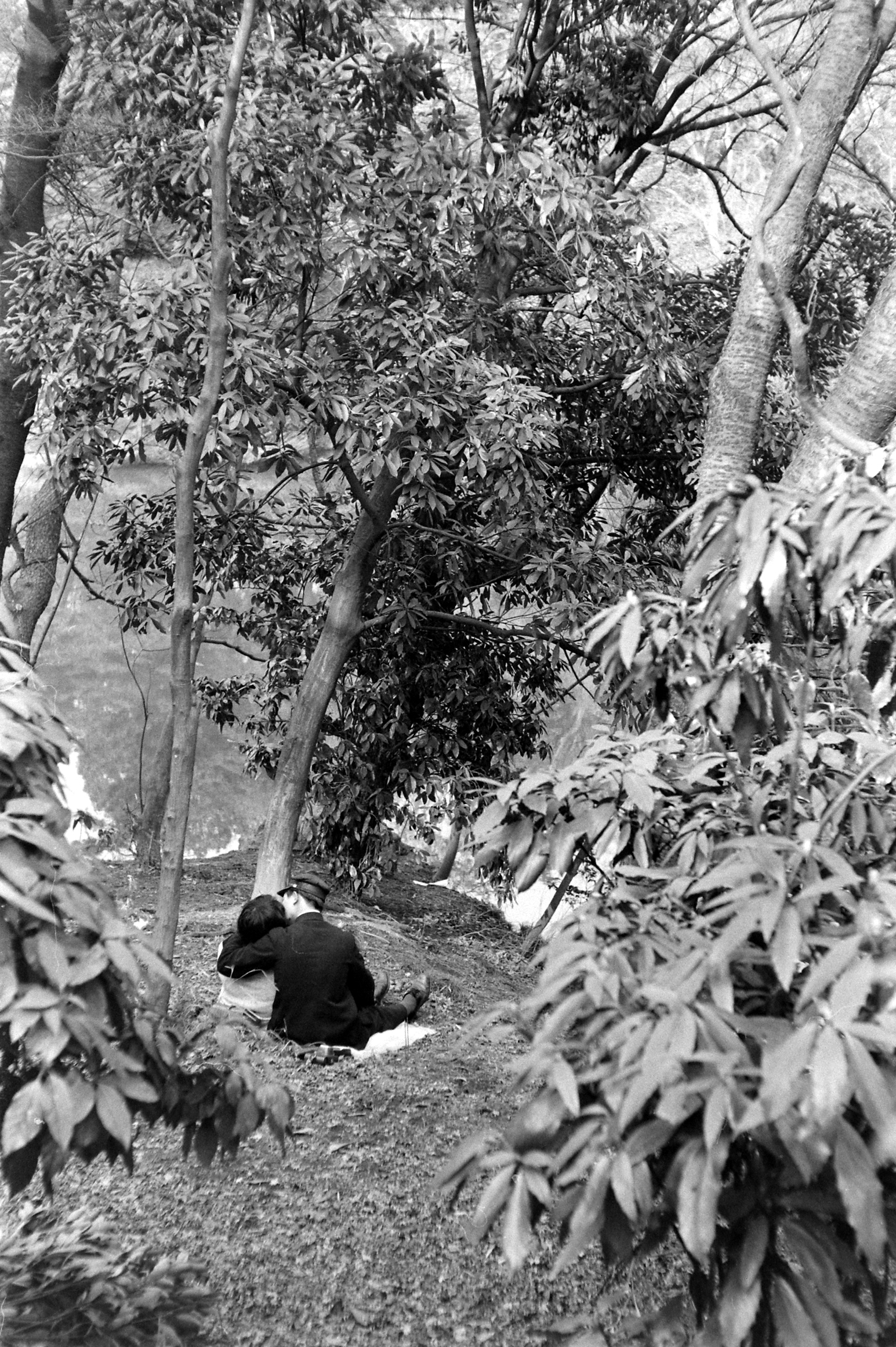

Whether accompanied by their visiting wives, Japanese girlfriends or prostitutes known as “pan pan girls,” American soldiers modeled the behavior they knew from home: public displays of affection and leisure time spent with women at cafés, parks or the movies. And inside those movie theaters, American movies offered even more examples of Western mating rituals to a Japanese public at once hesitant and intrigued by the bold behaviors of their American counterparts.

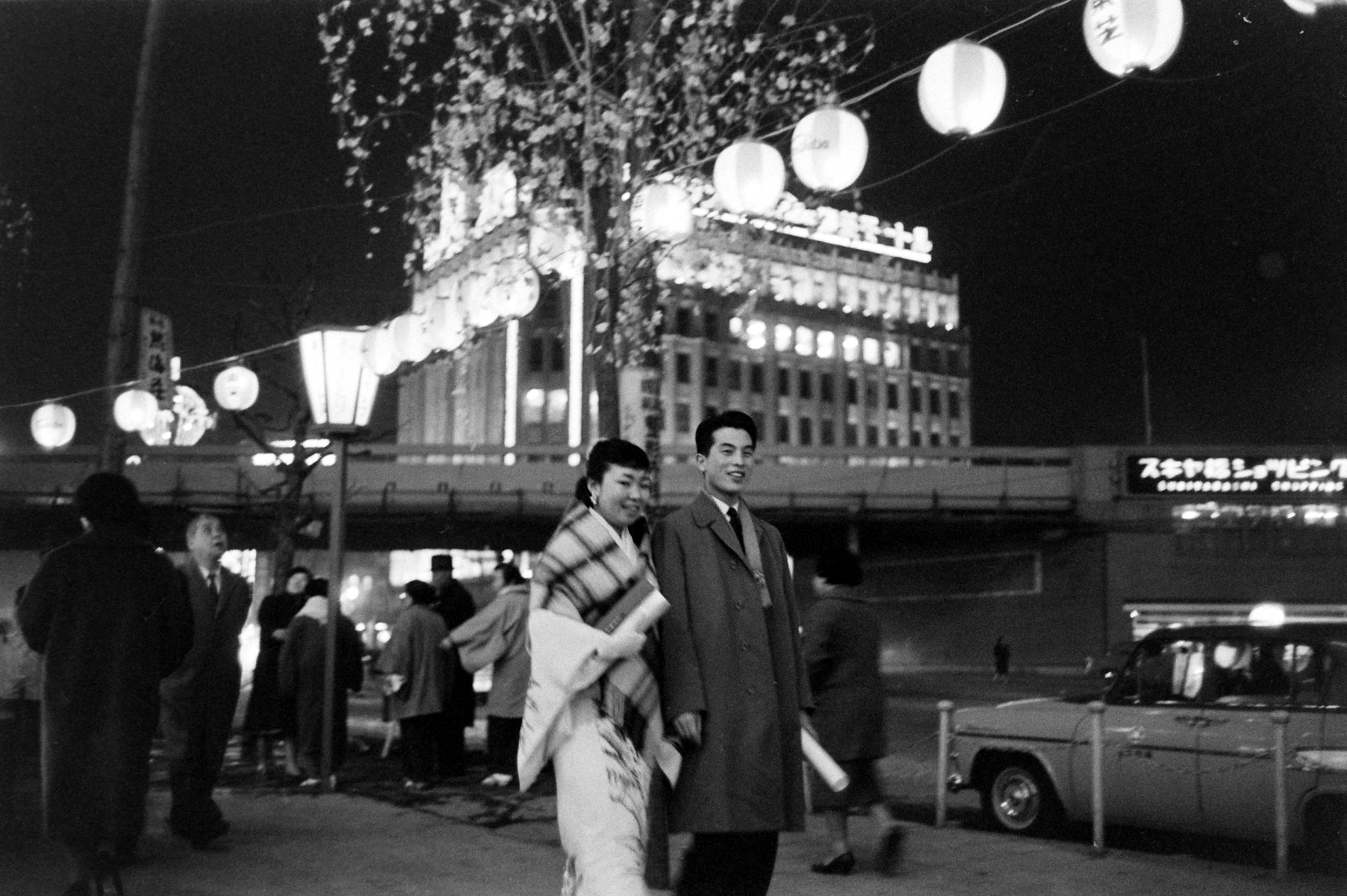

In his photographs—which never ran in LIFE—Dominis captured a moment when the new had caught on, but the old had not yet been forgotten. The young couples he photographed in 1959 were living on the edge of modernity, but still holding onto many of the the traditions long followed by their culture.

Notes written by Dominis and someone who appears to be an assistant that accompanied the dozens of rolls of film he shot provide insight into the song and dance (sometimes literal) in which the young lovers engaged. Some met by chance, others in settings tailor-made for matchmaking.

One of these settings was the “Shibui” dance, run by a man of the same name. For $2.50, young men and women could attend a night of dinner and dancing with the express purpose of introducing eligible bachelors to single young women. Upon arrival, new members bowed to one another and offered the greeting “yoroshiku,” described as “a very loose greeting which is used to fit any situation and in this case meaning ‘I hope I can find a mate among you.’” During dinner, partygoers were expected to “learn proper manner of eating western food.” If a young man found a young woman intriguing, he was not allowed to leave with her. Instead, he would tell Mr. Shibui, who would then arrange a date if the feelings were mutual.

One young couple, Akiksuke Tsutsui and Chiyoko Inami, met when Chiyoko, who worked at a bank in the same building as Akiksuke’s father’s clothing shop, began frequenting the shop during breaks. When Akiksuke brought Chiyoko to meet his family—after several outings to the beach, cafés, beer halls and department stores—his siblings welcomed her in ways that reflected the changing times. His younger brother showed off his Western knowledge by demonstrating how to swing a baseball bat and singing a rockabilly song. His sisters, meanwhile, sang Chiyoko Japanese folk songs.

Before meeting Akiksuke, Chiyoko had had five meetings with potential husbands, all arranged by her family. During these meetings, the young man and woman walked past each other in a Japanese garden, catching a quick glimpse of their potential mate, and delivering a decision to a go-between. Chiyoko had declined them all.

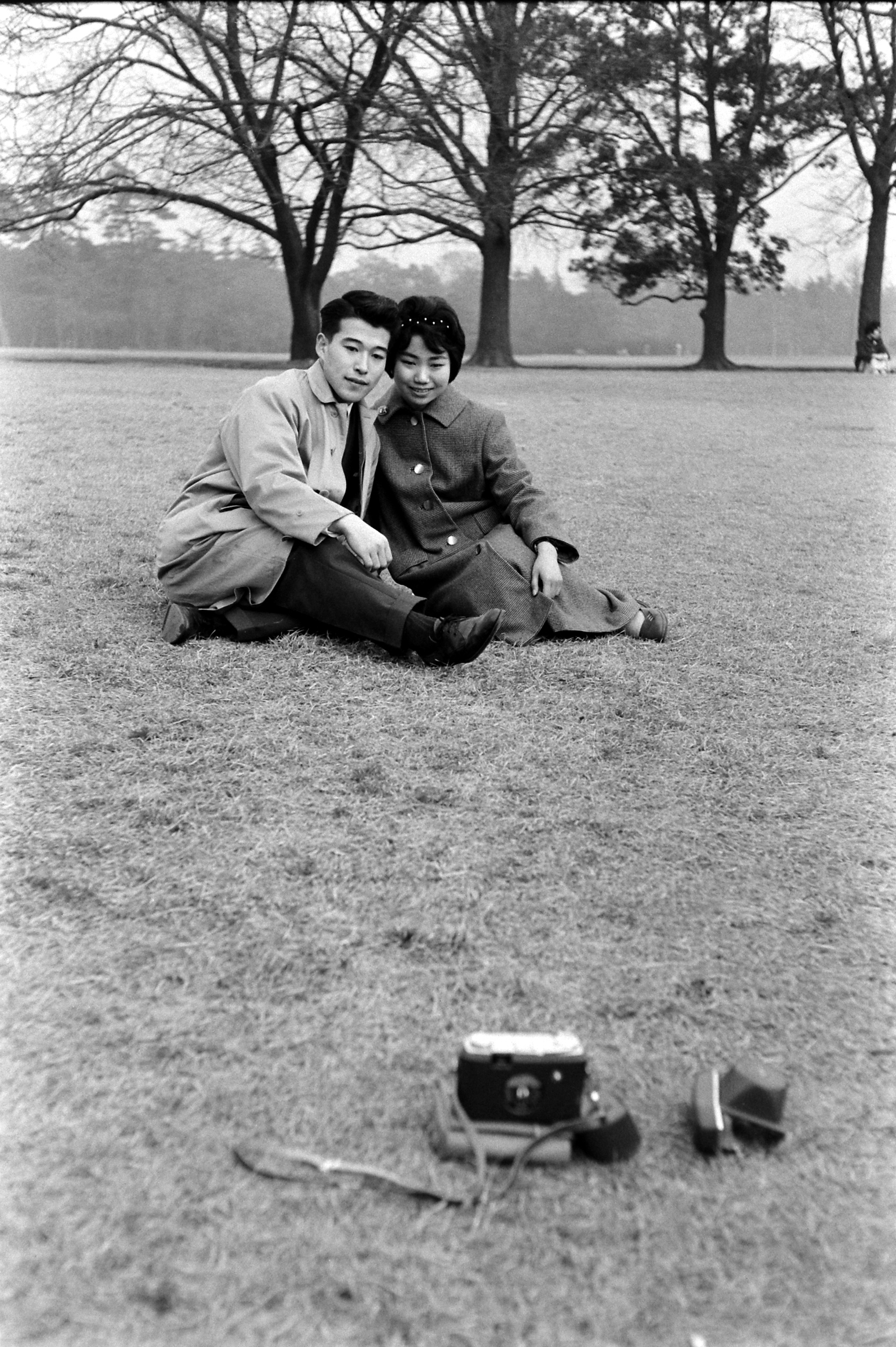

Dominis also photographed Takahide Inayama and Mitsuyo Ogama, two university students in their early 20s. The pair met six months prior, at Takahide’s house, when a friend of his brother’s brought her to a party there. Takahide and Mitsuyo, in a better financial position than some of the others, led Dominis to make an observation about class and marriage. “Most couples in Tokyo just can’t afford to get married until the guy is around 30 unless they both work or he has an exceptional job, or there is money in the family,” he wrote. “These kids go out with other couples and act more or less like you would expect western young lovers to act.”

While the photographs capture the increasing normalization of modern Western customs in Japan, they also exhibit the excitement and tenderness of being allowed to choose—a privilege which, of course, includes the right to opt out. “Two of the couples have since broken up,” reads a note from the files, “and are being shy about letting us know whether they have taken up with new friends.”

AnRong Xu, who edited this gallery, is a contributor to LightBox. Follow him on Instagram @Anrizzy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com